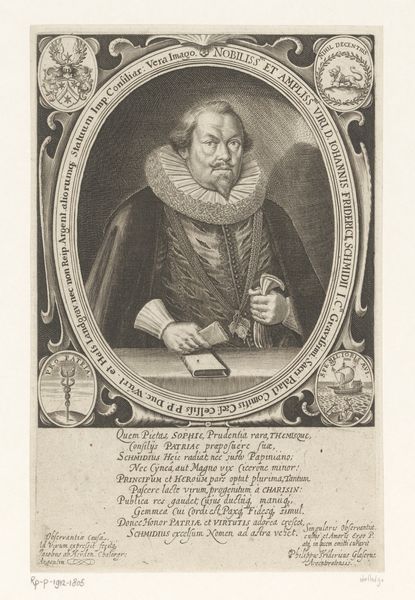

Portret van Johann Friedrich Schmidmair von Schwarzenbruck 1669 - 1720

0:00

0:00

johannalexanderboner

Rijksmuseum

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 231 mm, width 140 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Johann Alexander Böner's "Portret van Johann Friedrich Schmidmair von Schwarzenbruck," created sometime between 1669 and 1720. It's an engraving, and it gives the impression of solemn formality, like it was made for an official purpose. How do you interpret this work, thinking about the materials? Curator: Well, seeing this engraving, I'm immediately drawn to consider the socioeconomic conditions of its production. This isn’t simply a representation of a man; it is the product of very specific labor, tools, and an economy of printmaking. Böner utilized engraving – a process requiring significant skill and time – suggesting a market and desire for reproduced imagery, further consider the availability of different types of papers, ink, and presses at that time. Editor: That's interesting. I hadn't considered the process itself as part of the meaning. Curator: Exactly. Think about it: Why engrave a portrait instead of painting it? Engravings enabled the dissemination of images to a wider audience beyond the wealthy elite. Was it intended as propaganda, remembrance, or some other form of cultural capital for the subject's family or associates? These prints were circulated and consumed, which contributes to this person's legacy and reputation. Editor: So the material choices and the reproduction process become intertwined with social status and influence. How does this challenge traditional art historical ideas, that are focused on the genius of the artist? Curator: It repositions it entirely. Instead of solely glorifying the artist, we examine the artisan, the patrons, and the society that supported and consumed this printed image. It forces us to ask: Who controlled the means of production and who benefited? The answers can be quite revealing. Editor: I see what you mean! It really makes you think about art as something embedded within systems of labor and distribution, not just aesthetics or artistic vision. Curator: Precisely. By focusing on materiality and means of production, we expose the layers of social context that give meaning to even the simplest of engravings. We look at the role played by this particular mode of artistic making in 17th- and 18th-century European society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.