drawing, pencil, graphite

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

graphite

#

realism

Dimensions: height 500 mm, width 328 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

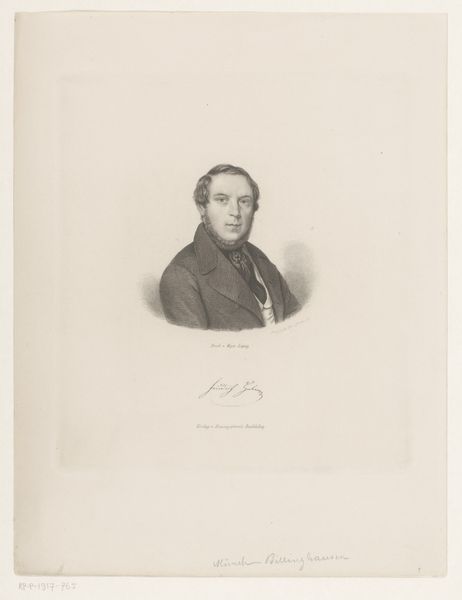

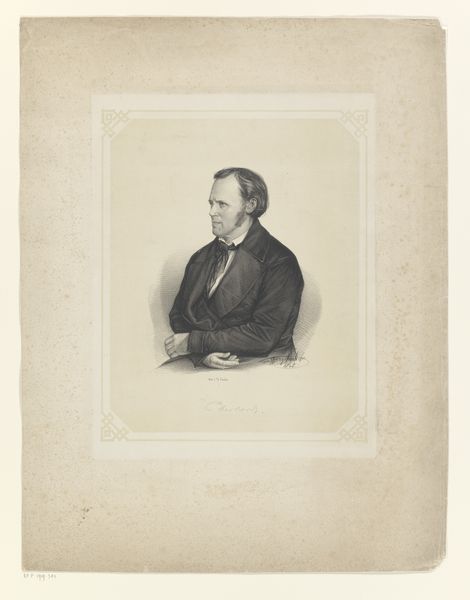

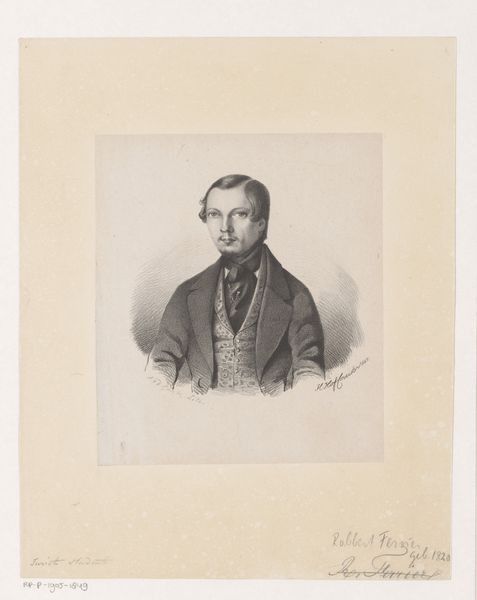

Editor: Here we have Johan Hendrik Hoffmeister's "Portret van Cornelis Schiffer," created sometime between 1833 and 1904. It's a graphite drawing, quite detailed. I’m immediately drawn to the subject’s direct gaze, it feels very… self-assured. What strikes you about this portrait? Curator: It's interesting you say that, because what immediately comes to mind is the context in which this portrait was made. During that time, portraits served a very specific social function – primarily to reinforce the power and status of the sitter, often a member of the bourgeoisie. Does his pose, his attire…do those read to you as assertions of identity and social standing? Editor: Definitely, his clothing screams status. But I suppose I hadn’t considered the *act* of portraiture itself as an assertion of power. Curator: Think about who could afford to commission or sit for portraits then. It’s rarely a cross-section of society! How might the choices around his clothing – the cut of his jacket, the knot of his tie – subtly signal particular values, or even political allegiances? Editor: I guess it’s about belonging and aligning yourself with specific groups. Was there anything particularly rebellious or forward-thinking about Hoffmeister's approach here? Curator: Perhaps not in its overt visual language, but one could argue that even replicating the codes of power becomes a form of engaging with them, forcing a dialogue around who is represented and why. Does this change how you see the work? Editor: It does. It’s no longer just a portrait, it's part of a bigger conversation about societal power dynamics and representation. Thank you. Curator: And thank you; you have sharpened my thoughts on how tradition can play a crucial role in identity formation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.