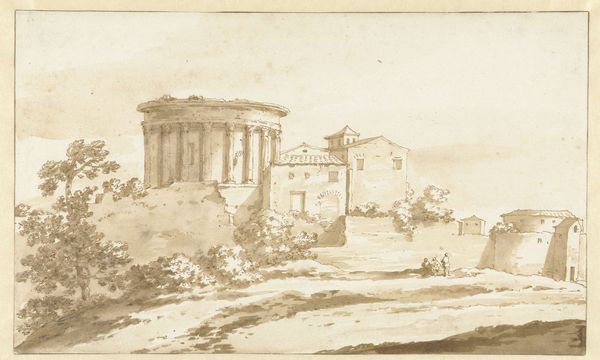

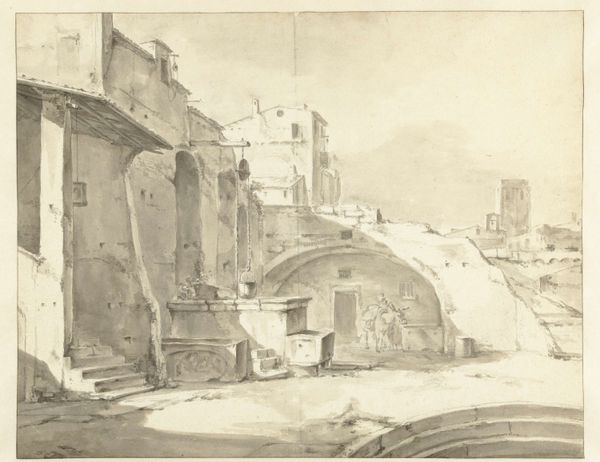

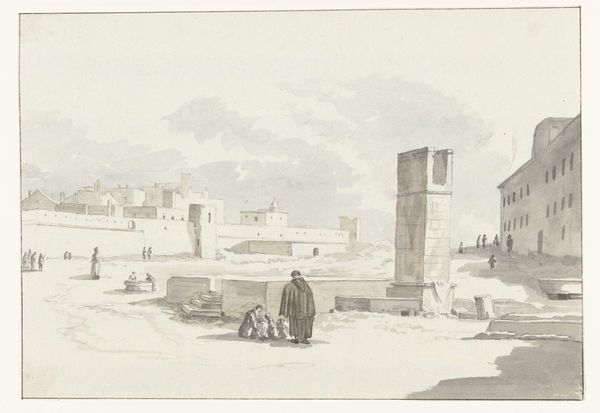

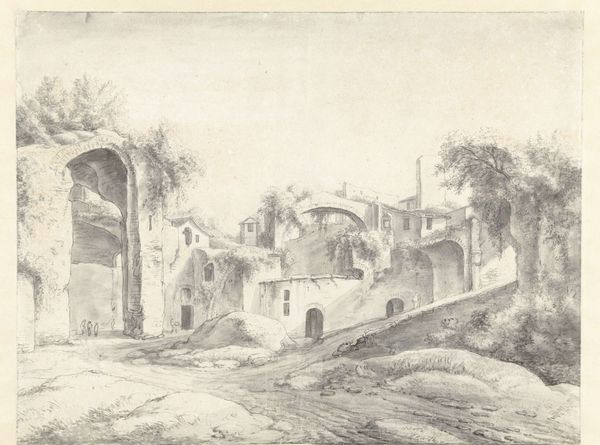

drawing, watercolor, ink

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

romanesque

#

watercolor

#

ink

#

cityscape

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 200 mm, width 334 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

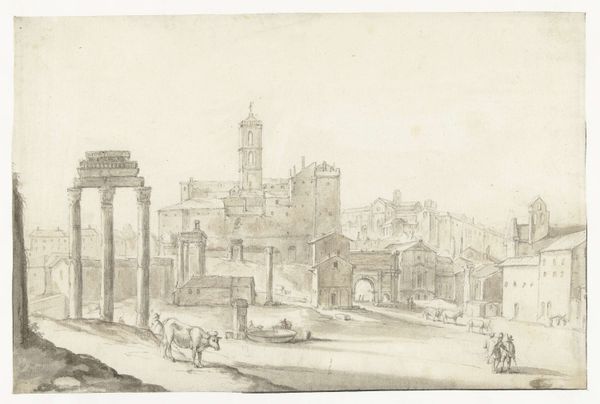

Editor: This is "Gezicht te Rome" – View of Rome – made between 1637 and 1689, by Jacob van der Ulft, rendered in ink and watercolor. It feels muted, almost dreamlike. The architecture is so present; how would you approach this work? Curator: Considering its materiality, look at the layered washes of ink and watercolor. How do these translucent materials work to represent, or rather, construct "Rome"? Ulft isn’t giving us an objective record, but a version, built through the application of pigment to paper. Editor: So you're suggesting the artwork's meaning lies in how it's physically created and what that says about the representation of Rome, as opposed to just what the image shows? Curator: Exactly. Think about the consumption of imagery in the 17th century. Travelers wanted souvenirs, portable versions of their experiences. Ulft’s workshop would have efficiently produced these views. Is this ‘high art,’ or a commodity responding to a demand? And consider the labour – who ground the pigments, prepared the paper? These “minor” tasks are intrinsic to the creation of the image. Editor: That definitely shifts my perspective! It connects the image to a whole economy. So, seeing this as a commodity – a product of artistic labour intended for consumption – what does that suggest about the artist's intent or the experience of owning such a work? Curator: The drawing is then less about *being* in Rome and more about *possessing* a version of Rome. What is the economic transaction embedded here? Also, how might the quick, repeatable nature of watercolor – ideal for rapid reproduction – democratize access to the image of Rome, beyond just wealthy elites? Editor: That's fascinating – I never would have considered the social and economic layers inherent in the creation of what appears to be a simple landscape drawing! Curator: Thinking through material processes opens up a wealth of interpretive possibilities. It encourages us to examine the how and why of artmaking, and the world in which art circulates.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.