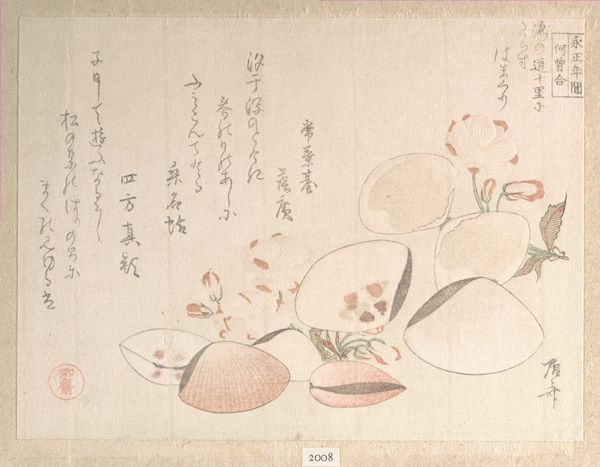

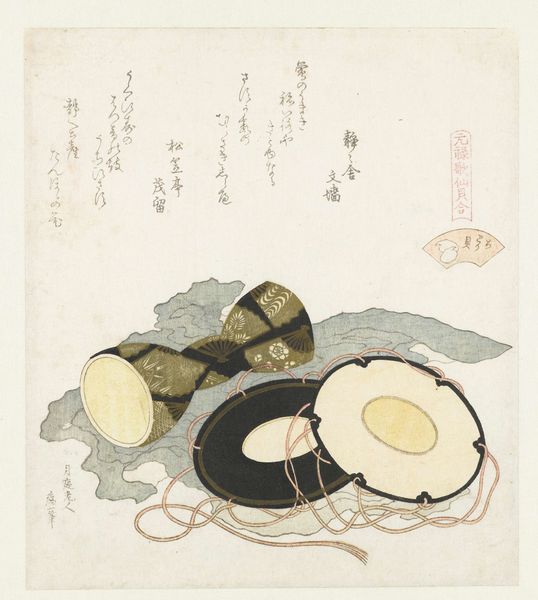

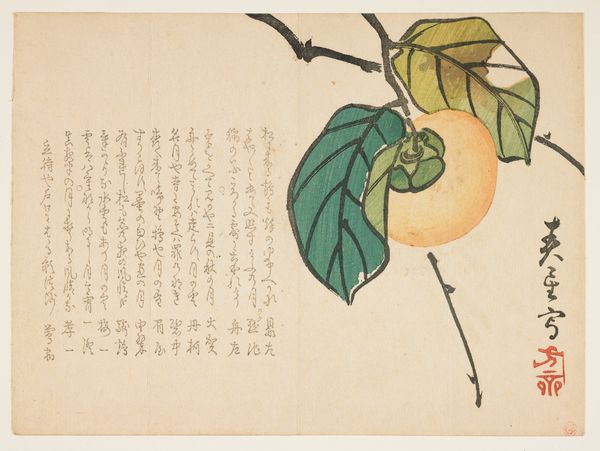

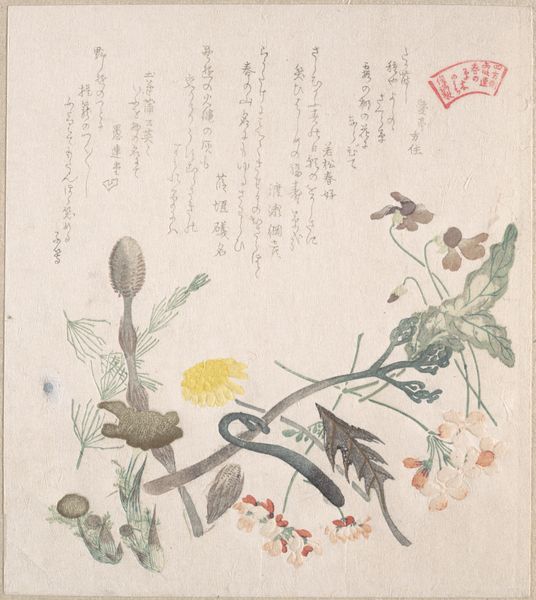

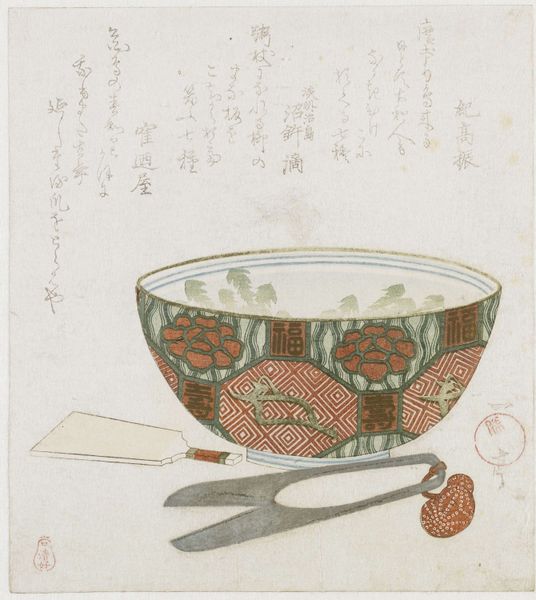

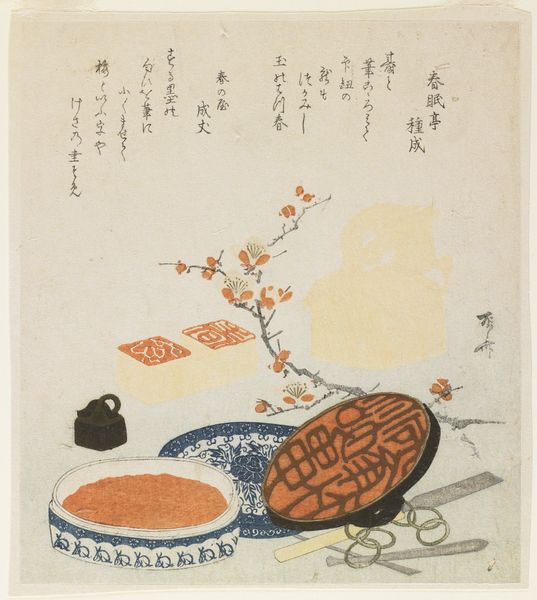

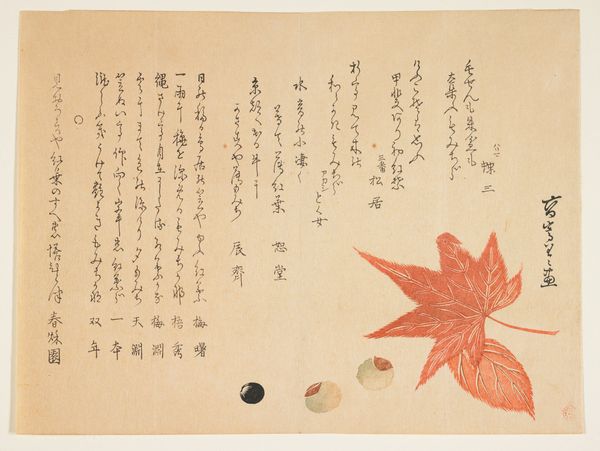

Orange, Dried Persimmons, Herring-Roe and Different Nuts; Food Used for the Celebration of the New Year 19th century

0:00

0:00

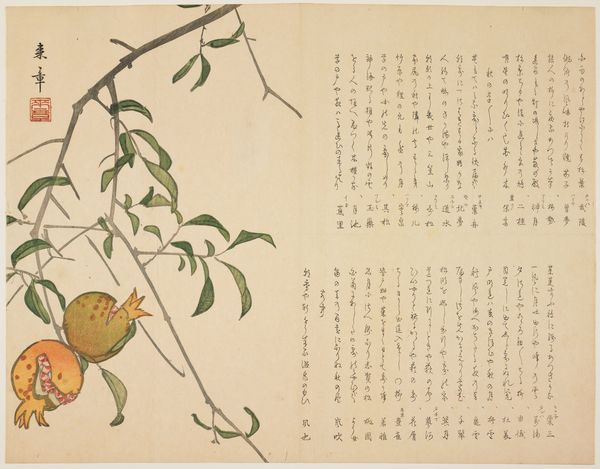

print, woodblock-print

#

fish

#

water colours

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

japan

#

curved letter used

#

personal sketchbook

#

fruit

#

woodblock-print

Dimensions: 5 1/2 x 7 7/16 in. (14 x 18.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Ryūryūkyo Shinsai’s “Orange, Dried Persimmons, Herring-Roe and Different Nuts; Food Used for the Celebration of the New Year” is a 19th-century woodblock print, now residing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Its understated elegance is arresting, isn’t it? Editor: I find it more strange than elegant, actually. It is humble… but also strangely melancholic for a new year celebration. There’s a stillness to it. Look at how simply the objects are presented, devoid of almost any background. I'm drawn to the artist's consideration of the material quality of daily life, and I want to understand how these particular foods shape communal life and identity. Curator: Well, that simplicity, combined with the choice of foods, really speaks to specific New Year traditions of the Edo period. Each ingredient had symbolic meaning for the Japanese. It served as a visual shorthand, celebrating wishes for prosperity, fertility, and health in the coming year. And don't you see how, together, they represented something about the communal and even gendered hope embedded in their labor and culinary processes? Editor: Certainly the act of preparing these ingredients involved labor, and accessing them would also relate to commerce in a time of strict hierarchy. Take the nuts. What did they mean for the consumer classes in Japan, given material realities around wealth and income distribution? Even though prints like this circulated to a broader audience, how much agency did commoners have in determining what made up their meals and New Year? Curator: Those are crucial points to raise about consumption and access, though I also wonder how the creation and distribution of these ukiyo-e prints contributed to constructing class identity during the Edo period, by circulating this very idealized image. This might serve as both aspirational and didactic at once, creating belonging for some and setting barriers for others. Editor: That tension you point out is useful: did prints like this offer an opening to explore one's material realities? The materiality of the ink, paper, the woodblocks themselves— they circulated to people to communicate particular realities, desires, and limitations, don’t you think? Curator: Exactly! This quiet scene whispers about rituals, hopes, but also the inherent social and economic structures underlying daily existence, reminding us how celebrations themselves become tools in society-building. Editor: A powerful reminder that even depictions of quotidian materiality such as this can hold multiple truths simultaneously. Thanks for offering an art historical interpretation. Curator: Thank you; your materialist viewpoint has given me fresh appreciation for how objects, even those seemingly humble, mediate our place in society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.