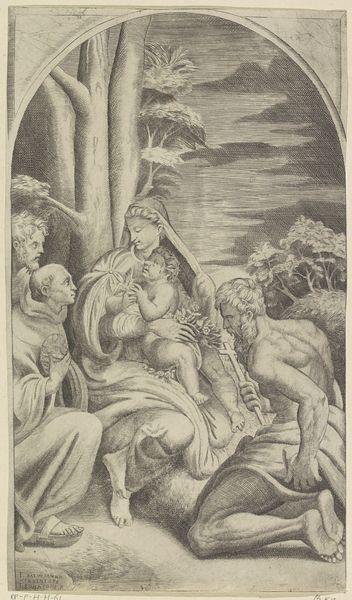

The entombment of Christ, the crosses on Calvary visble in left background 1563

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

landscape

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: sheet: 11 7/16 x 7 in. (29.1 x 17.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Giulio Bonasone's 1563 engraving, "The Entombment of Christ," held here at the Metropolitan Museum, captures a poignant scene rendered with incredible detail. What strikes you first about this image? Editor: The emotional weight. The somber mood is palpable; the weight of grief is literally etched into every line. You can almost hear the soft weeping. Curator: Indeed. Consider Bonasone’s meticulous technique; the crosshatching alone suggests countless hours of labor. This piece prompts us to think about the means of reproduction, the accessibility an engraving offered versus, say, a painting. These prints circulated widely. Editor: Exactly. These images were consumed and contemplated by a far broader audience. I think about the socio-political context—the anxieties of the Reformation, the evolving relationship between the church and its followers. Did this piece speak to or challenge that dynamic? The women especially: their active grief resonates with ideas of female piety and defiance of structures. Curator: The material reality shapes those ideas. Engraving involves intense physical labor. And Bonasone, while emulating masters like Raphael, was still participating in a market economy. What was his workshop like? Who assisted in production? These hands, and these tools… Editor: Yes, and thinking about this from a perspective that looks at gendered labor... We see in the background those stark crosses—silent sentinels—a reminder of Roman imperial power and their method for squashing rebellion. Is there any way to resist the weight of such systems of oppression? And how does the inclusion of the grieving women specifically highlight that power structure? Curator: The materiality further underscores this relationship of resistance or resignation. The stark contrasts created through engraving highlight the themes of light and shadow, perhaps metaphors for good and evil? The accessibility afforded by printmaking opens new avenues for critique as much as reverence, for profit, and propaganda. Editor: That interplay, the tension between tradition and revolution, speaks volumes to today’s ongoing dialogues about identity, marginalization, and resistance to power structures. It highlights how important understanding production is. Curator: Ultimately, this piece is far more than religious iconography, it’s an artifact tied to production, reproduction, and distribution within a shifting world, one crafted by many hands along the way. Editor: Yes. It pushes us to actively question how images participate in perpetuating systems, and maybe how they resist them.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.