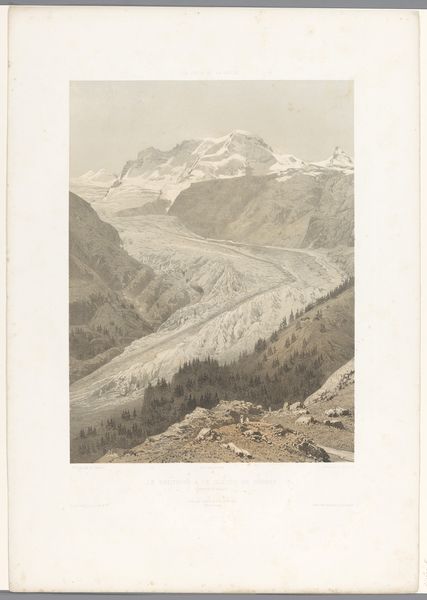

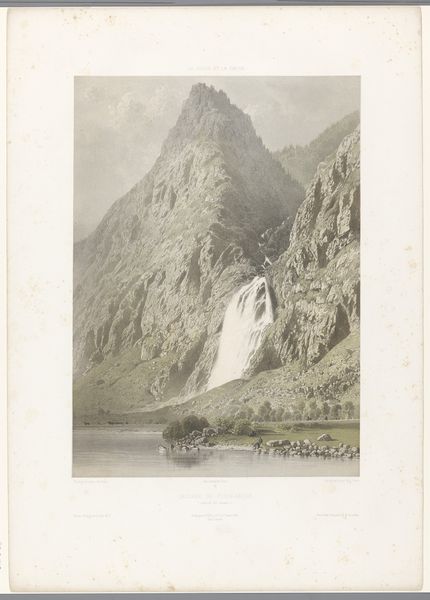

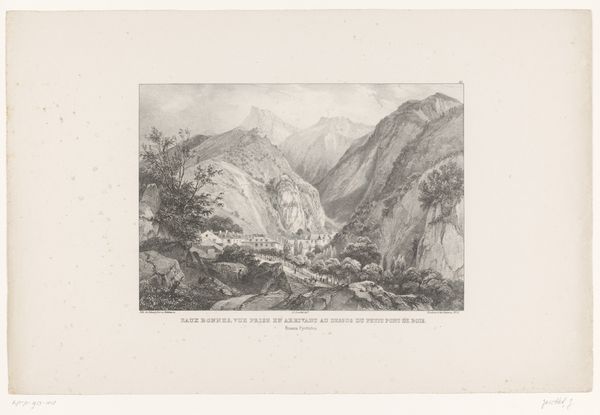

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

coloured pencil

#

realism

Dimensions: height 565 mm, width 400 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

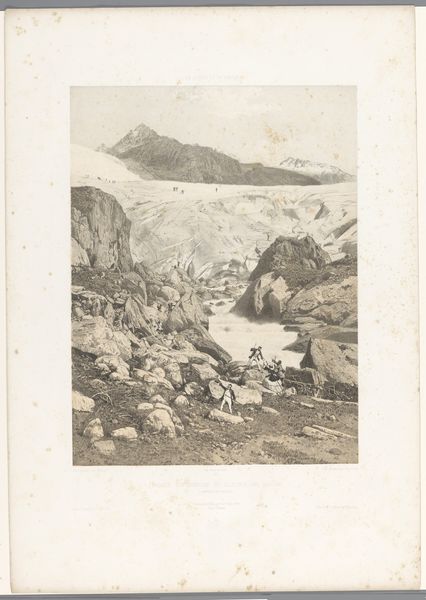

Curator: Eugène Cicéri's "View of the Upper Grindelwald Glacier," created in 1859, greets us today. Crafted with ink and coloured pencil on paper, it offers a window into a world of dramatic contrasts. Editor: My first impression is how it captures the sublime. The imposing glacier juxtaposed with those tiny human figures and rustic buildings... there's an inherent power dynamic being visualised. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the glacier itself. It's a powerful symbol of nature’s immutable force, its slow yet relentless movement shaping the landscape over millennia. The sheer scale conveys that power but also evokes ideas about ephemerality, reflecting perhaps a Romantic fascination with ruins and cycles of time. Editor: Right. The settlement in the foreground then reads as precarious, dwarfed by this natural phenomenon. It’s as if the artwork’s highlighting our transient existence, set against the geological timescale of the glacier's existence. Curator: Look closer, though, at the human details – the figures traveling along the road. Even in the face of such overwhelming natural power, life goes on. There's a sense of industriousness and resilience – a microcosm of society pressing on amidst a colossal setting. The ink drawings and coloured pencils also allow for an expression of delicate gradations, creating texture and form. Editor: And what of those gradations? A sense of both social stratification and hierarchy is subtly reflected in this seemingly pastoral landscape. The artist clearly isn’t offering just a snapshot; he’s framing the dynamic interactions between society, nature, and perhaps even class. The fact it’s rendered with such detail begs us to consider, who is afforded protection from this landscape, and who is not? Curator: Interesting! It prompts a reading about historical context. Nineteenth-century travel in the Alps became increasingly fashionable for the bourgeoisie. Consider this work alongside its wider historical implications concerning class and nature as a spectacle for consumption. Editor: Indeed. A powerful commentary using a seemingly straightforward landscape. Curator: Cicéri gives us the glacier as something awe-inspiring, while the human world struggles along the thin margin, coexisting—though perhaps always overshadowed—by its might. Editor: Leaving us with more questions about what sustainability meant, even in the Victorian era, while pondering what it truly means now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.