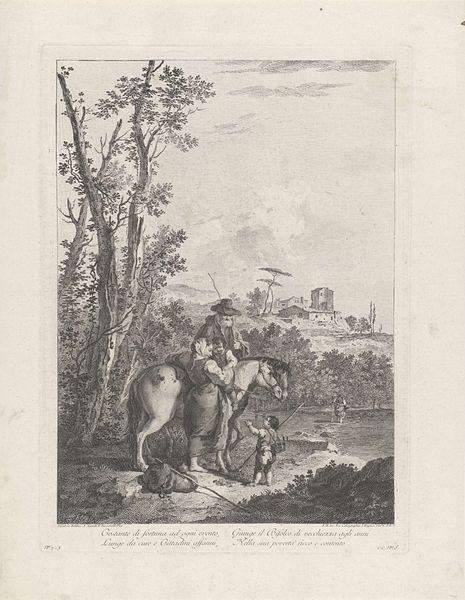

print, engraving

#

comic strip sketch

#

quirky sketch

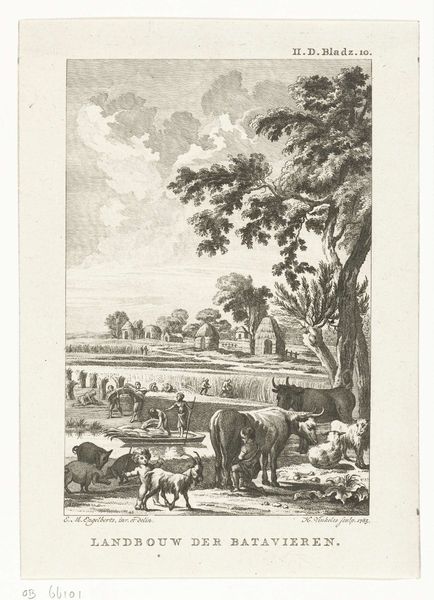

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

romanticism

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

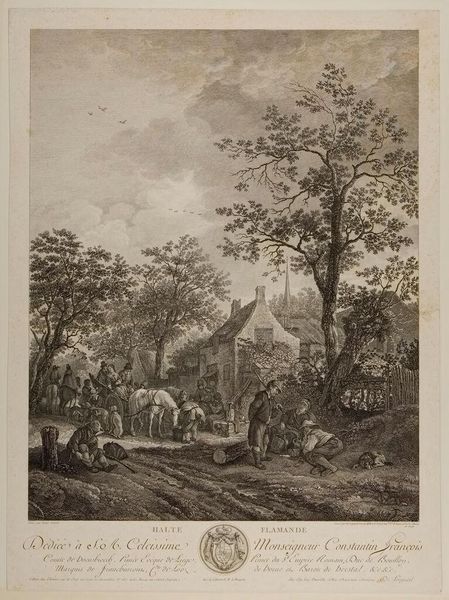

genre-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 255 mm, width 188 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Today, we’re looking at “Watermolen, ruïne en herderin,” or “Watermill, Ruin, and Shepherdess,” an engraving by Fréderic Théodore Faber from 1807, currently held in the Rijksmuseum. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: Well, it's a world steeped in romantic nostalgia, wouldn't you say? The composition feels like a constructed idyll, but one burdened with class tension and unequal burdens for its characters. Curator: I see what you mean. Formally, it's a complex arrangement of multiple scenes within a single print, reminiscent of a page from a sketchbook or a carefully constructed allegory. Look at the details in the linework—how would you describe Faber's handling of light and texture? Editor: The figures and landscape elements do exhibit Faber's attention to light and shadow to sculpt depth using linear hatching and cross-hatching, creating a sense of atmospheric perspective. However, I’m intrigued by what's included, what is omitted. Notice the loaded donkey carrying goods led by the female peasant, and juxtapose her condition with that of the man sitting leisurely on his stead: this seems to present two differing perspectives in their era. Curator: Indeed. The division of the picture plane creates this layering. Each distinct scene showcases Faber’s attention to proportion and placement: he carefully offsets the pastoral, open air scenes with enclosed building structures and a rather theatrical grouping near ruins. Editor: This is precisely the moment in which we consider the cultural dimensions of such constructed representations: during the romantic era, the idea of nationhood became heavily entwined with these representations of peasantry—they weren’t just decorative; they were integral components within the nation's self image, defining an entire political landscape for years to come. The laboring pastoral idealized while it actively disenfranchised a great segment of Dutch society. Curator: Fascinating. So, by drawing attention to these seemingly 'minor' figures within these compositions, you’re re-evaluating the larger power structures embedded within Faber's idealized Romanticism. Editor: Precisely. It’s about unsettling what’s presented as inevitable—it shows us how deeply socio-economic inequities have long been disguised under aesthetic veils, but also provides agency through our new understanding. Curator: Thank you. That’s provided us with a compelling multi-layered approach to reading a seemingly simple engraving. Editor: Indeed. Hopefully, our insights shed light onto the intricate tapestry between artistic expression and broader historical discourse.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.