drawing, print, etching, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

ink painting

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

charcoal drawing

#

paper

#

ink

#

watercolour illustration

#

watercolor

#

realism

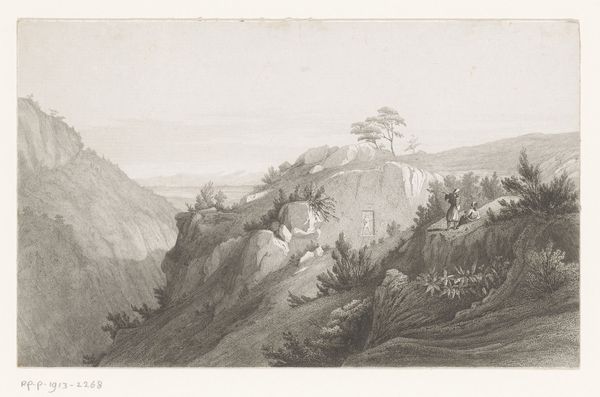

Dimensions: height 196 mm, width 301 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

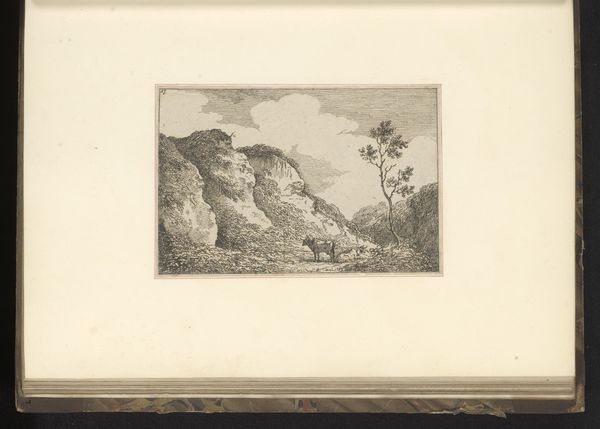

Curator: Let's consider "Landschap met een jager bij rotsen" – "Landscape with a Hunter by Rocks," a print dating from around 1789-1790, crafted with etching and ink by Edward Edwards. Editor: Immediately striking is the dramatic contrast between the light, almost airy sky, and the densely worked textures of the rocks and trees. It's quite an evocative scene; I feel a sense of both tranquility and perhaps isolation. Curator: It is a fine example of Neoclassical landscape art, quite in vogue then. We can see a clear interest in depicting an idealized, almost Arcadian setting, but grounded with realistic elements. Editor: Idealized, but with this tiny figure of a hunter almost swallowed up by the landscape. Is this an artist subtly commenting on humanity's place within nature? Curator: Certainly, the prominence of the landscape compared to the human figure prompts consideration of such questions. Edwards was working at a time when notions of the sublime in nature were incredibly potent. The role of institutions in supporting the artists like Edwards shaped this imagery and his patronage network. Editor: I appreciate your bringing in the economics; his artistic license was directly influenced by the ruling structures and how landscapes fit into national and political identity at the time. This "untouched" nature wasn't divorced from power. Curator: Precisely. Furthermore, there’s a clear emphasis on rendering realistic textures and natural forms within that carefully composed framework, an engagement with Realism, which seems a subtle nod to this new focus in landscapes. Editor: It does walk that line, but the romantic spirit is ever-present. What do we make of the hunter himself? He seems… passive. More an observer than an actor in this landscape drama. It raises a few flags when considered from an identity lens. Curator: His quiet presence could symbolize humanity's harmonious relationship with nature – an echo of Enlightenment ideals. Or simply, the insignificance of our actions when seen against the scale of natural processes and natural art itself, since some philosophers view art as simply an enhanced type of production. Editor: Well, Edwards has provided ample material for thought. My understanding of the period enriches my response to art’s broader intersectional contexts. Curator: Indeed; hopefully our exploration has enhanced appreciation of its interplay of artistic, social and historical meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.