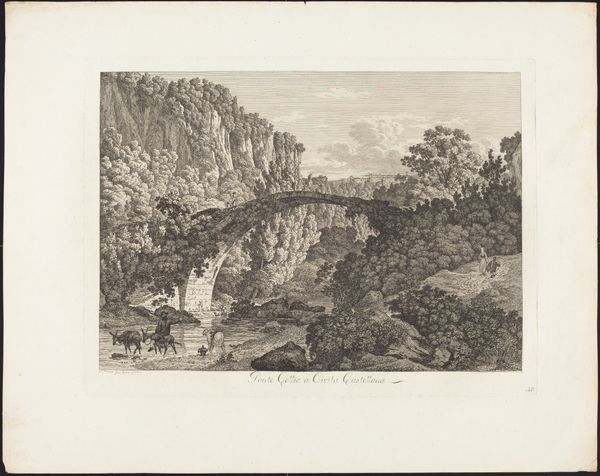

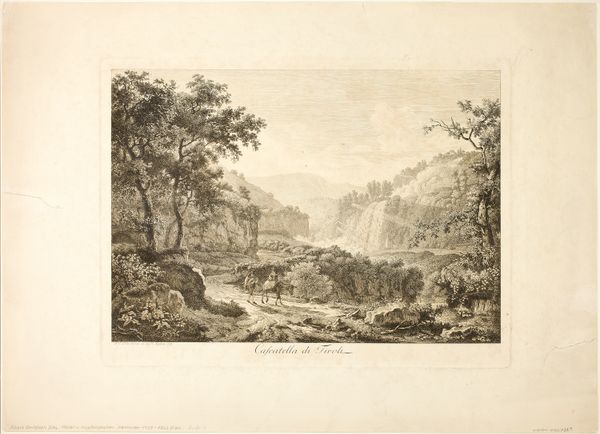

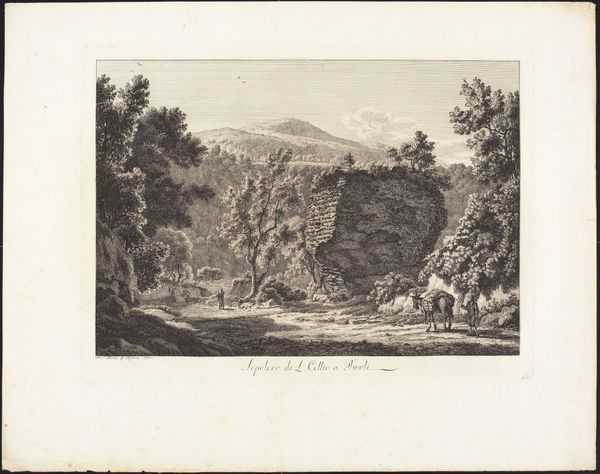

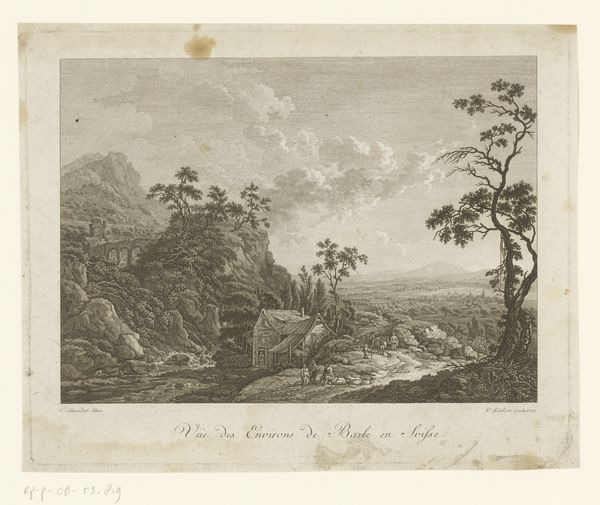

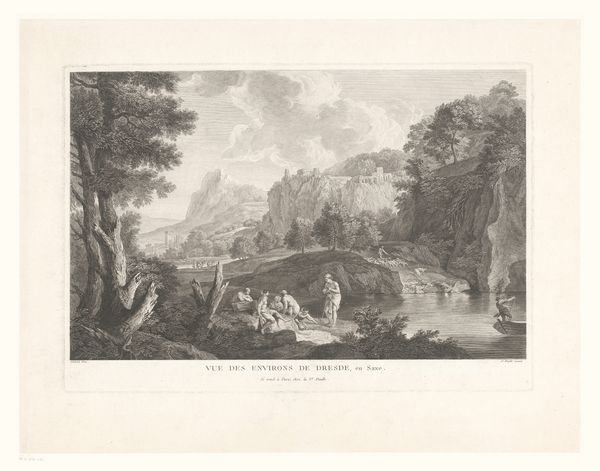

print, paper, engraving

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

# print

#

light coloured

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 168 mm, width 227 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have "Landschap met een rivier en rotsen," or "Landscape with a river and rocks," created sometime between 1798 and 1840 by Carl Schleich. It's a print, an engraving on paper. It has a very serene, almost melancholic feel. What strikes you most about it? Curator: I’m drawn to how this landscape, rendered in a style reminiscent of Romanticism, speaks to humanity’s complex relationship with the natural world. Notice how the scene emphasizes the sublimity of nature—the imposing rocks, the rushing river—but presented within the controlled format of a print. It makes me consider how, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, these representations were often deployed to solidify a sense of national identity intertwined with dominion over the landscape. What kind of social and political context do you imagine shapes how Schleich chose to depict the rocks and the river? Editor: I hadn’t thought about it like that. I suppose it's easy to see just the surface beauty without considering any hidden context, like how access to landscapes was often class-based or even race-based at that time. How does this awareness influence your interpretation? Curator: It forces us to ask: Whose perspective is being privileged? And whose is being erased? How might the working class, excluded from experiencing it at leisure, perceive such a scene of natural abundance? Perhaps through the engraving the work performs power over nature, subtly mirroring the othering of marginalized communities through colonialism, rationalism, and developing capitalism. Editor: That’s fascinating. Looking at it now, the image does seem to promote a specific kind of…ownership, doesn’t it? Like nature is there to be admired, perhaps even conquered, rather than lived within. Curator: Exactly. And by recognizing those undercurrents, we begin to unlock more profound dialogues about power, representation, and the enduring legacy of these images. Editor: I'll definitely view 19th-century landscape art differently now! Thanks. Curator: And I see now just how essential those perspectives remain in considering both art’s purpose and the purposes to which art is put.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.