Prinses Charlotte uitgespeeld met haar Hollandse tol, 1814 Possibly 1814 - 1817

0:00

0:00

georgecruikshank

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, watercolor

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

caricature

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

#

cartoon carciture

Dimensions: height 250 mm, width 355 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

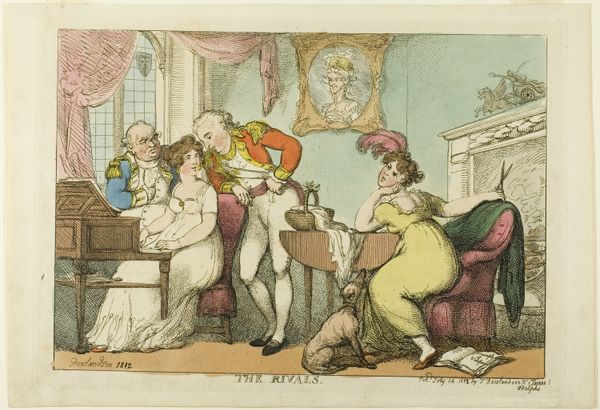

Curator: Immediately, I'm struck by the rather stiff formality, yet the subtle, almost saccharine palette creates a feeling of restrained agitation. It's an odd contrast. Editor: It is indeed, but look closer; we're seeing George Cruikshank’s, "Prinses Charlotte uitgespeeld met haar Hollandse tol", likely created between 1814 and 1817. Primarily executed in drawing and watercolor, it incorporates elements of printmaking to achieve its final form. Curator: Note how Cruikshank employs line and color to create a defined sense of space, however unrealistic; the eye moves from Princess Charlotte, along the axis created by her gaze, to the prince. Editor: More crucially, let's consider the material reality—Cruikshank's choices weren't arbitrary. Watercolor enabled the rapid dissemination of satirical images, catering to an expanding middle class. The etching, a printmaking technique, enabled him to reproduce the original image cheaply, thus facilitating access. This wasn’t "high art;" this was accessible cultural commentary, influencing public opinion in a tangible manner. Curator: That is interesting in this particular instance as there are obvious romantic elements—observe Charlotte’s dress and the aesthetic framing in the portrait to the background. However, in light of the cartoon carciture theme of the artwork this contrasts oddly. I question whether Cruikshank seeks to mock social romanticism. Editor: This is where an investigation of medium opens an aperture of critical insight; Romanticism was largely supported by wealthy families commissioning lavish portraiture, yet Cruikshank chose to implement print and caricature - enabling an undercurrent of accessible discourse against the more accepted aesthetic ideals of the day. Curator: It’s intriguing to observe how those romantic aesthetic strategies work to enhance, rather than undermine, the caricatured narrative of the piece as a whole. Editor: And the widespread appeal speaks volumes about the culture of critique being formed in 19th century Britain through the agency of production. What matters isn't the imitation, but the making of meaning. Curator: True enough. By interrogating both formal components and its social means, Cruikshank has achieved a remarkable balance. Editor: Yes, his commentary through his process provides additional layers of understanding that add to the image’s lasting relevance and subversive punch.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.