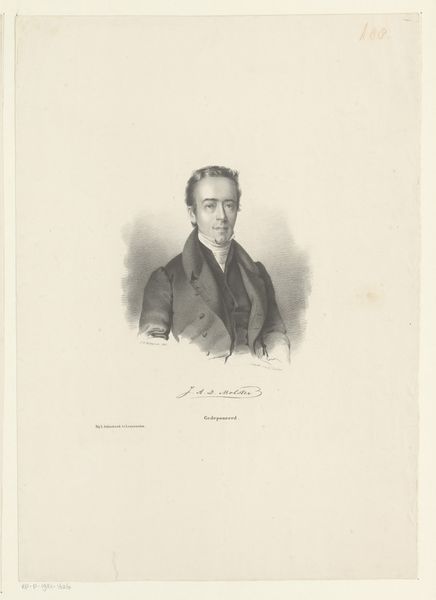

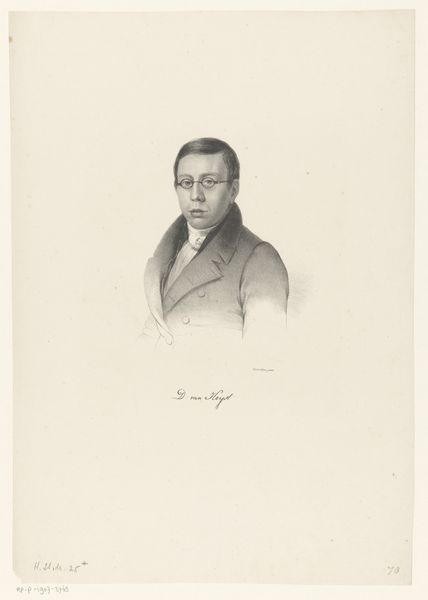

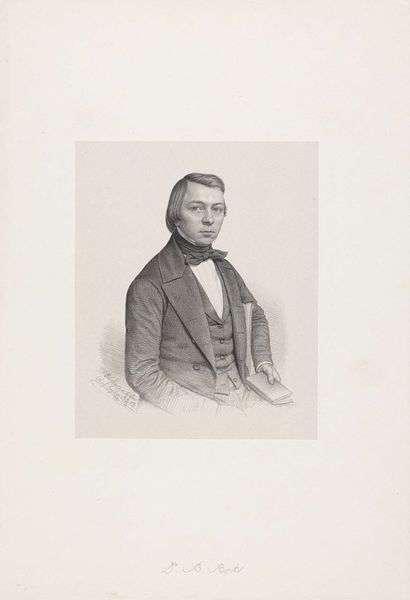

Portret van een onbekende man, mogelijk H.C.M. van Kerve Possibly 1855

0:00

0:00

johannpeterberghaus

Rijksmuseum

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

genre-painting

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 410 mm, width 315 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

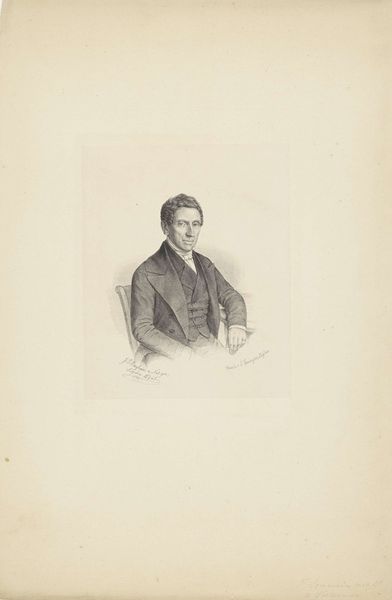

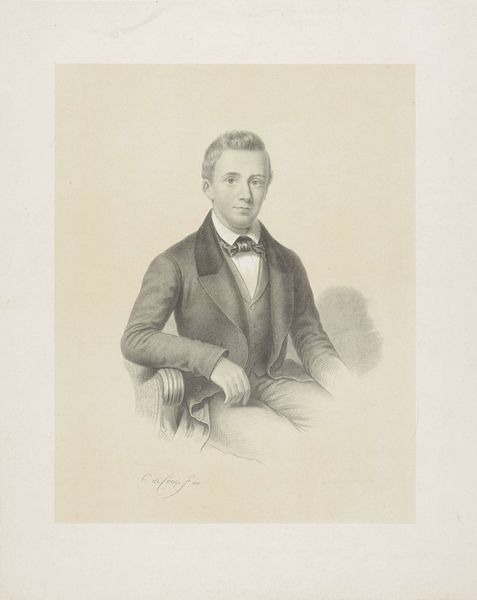

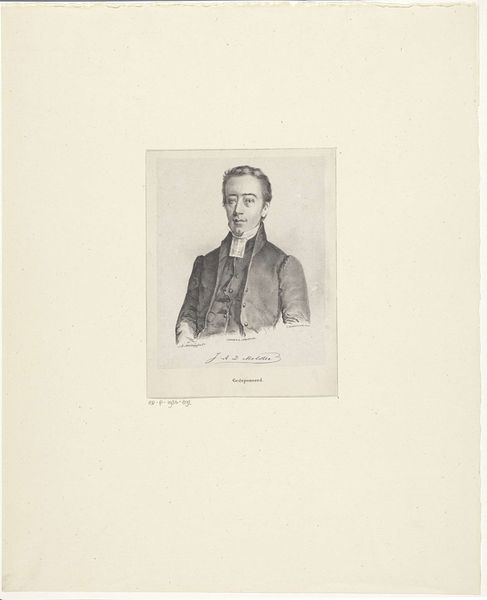

Curator: Here we have a pencil drawing titled "Portret van een onbekende man, mogelijk H.C.M. van Kerve," dating possibly to 1855 and housed right here at the Rijksmuseum. The artist is listed as Johann Peter Berghaus. Editor: There’s an intriguing gentility to it, wouldn't you say? The way the artist captured the slight smirk, juxtaposed against the formal attire—it hints at a quiet rebellion against the rigid social structures of the time. Curator: Indeed. And I'd say it does suggest the man pictured held a respectable position within the bourgeois class, a world where such outward displays of refined masculinity carried social and political meaning. His somewhat casual pose at a desk could hint to this subject's world being involved with the production or circulation of written matter. Editor: Right. The bow tie, too—a dash of flair amidst the dark jacket and waistcoat. A signifier, perhaps, of personal identity asserting itself within the confines of convention? How does this challenge the often-reproduced, very stern portrayal of men in Western Art, even to this day? Curator: Portraits, historically, did function as a demonstration of the sitter's station, conveying aspects of status, authority, or morality to those who viewed them, as an indicator of belonging to certain networks. But the man's softly modeled face, however, has an undeniable touch of romantic sensitivity to it. Editor: Precisely! And that sensibility complicates the reading, destabilizing a purely power-based interpretation. The gaze is level, but not confrontational, suggesting an openness, maybe even a plea for understanding. So how does the potential ambiguity of his identity impact our understanding of this image? Does it make him an emblem of every-man's struggle for individuality? Curator: Precisely. That missing identity elevates this image beyond the purely representational. Rather, that sense of universality transcends a mere chronicle of social history to evoke enduring notions of identity and self. The work resonates powerfully as a meditation on masculinity. Editor: The work seems to point at an undercurrent of yearning and introspectiveness beneath a facade of conventional masculinity. Curator: It's a subtle reminder, maybe even a powerful one, that the symbols and systems we read from portraits aren't as definite as they may at first seem. Editor: Right. It offers us some insight into the complex interiority of 19th-century individuals, just like many works that engage portraiture through our own lens of critical intersectionality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.