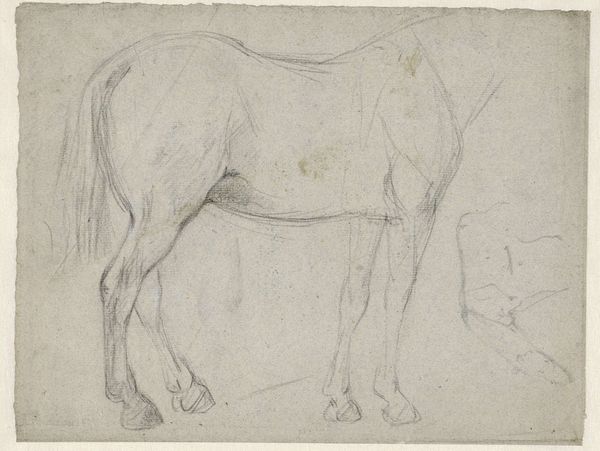

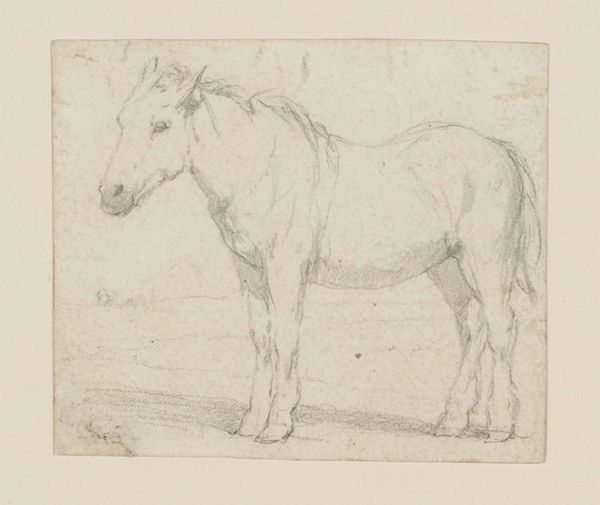

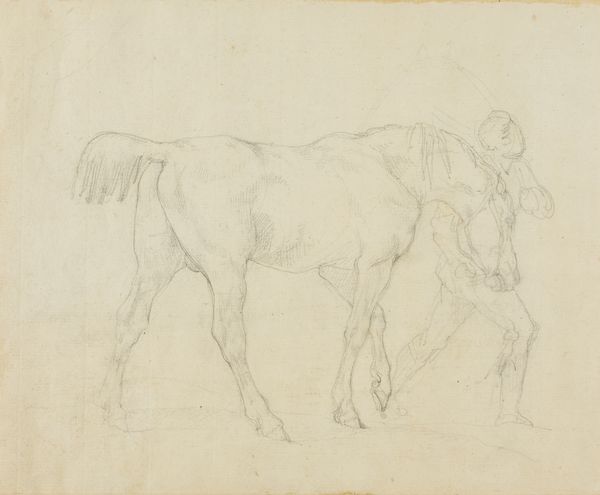

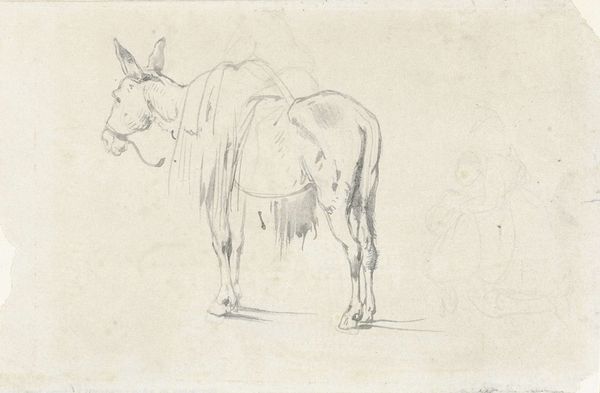

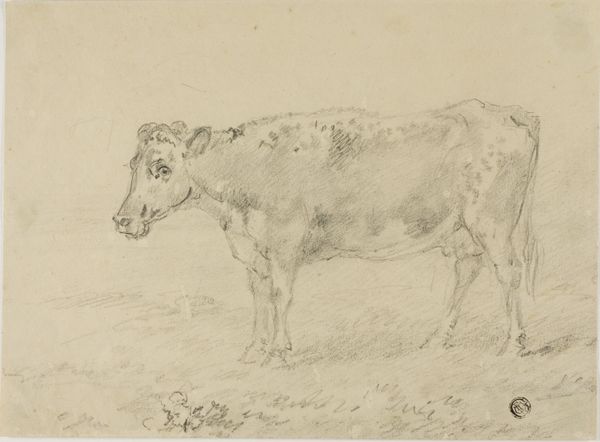

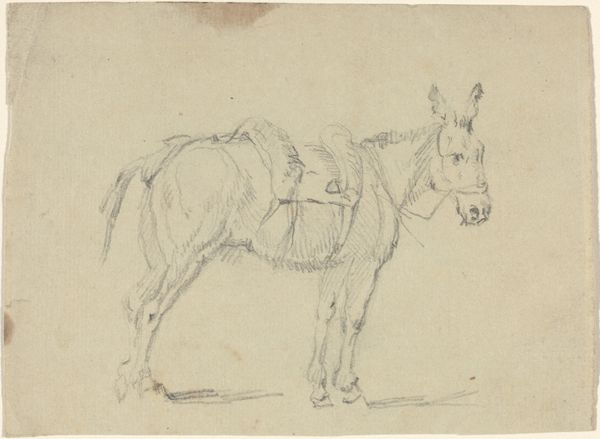

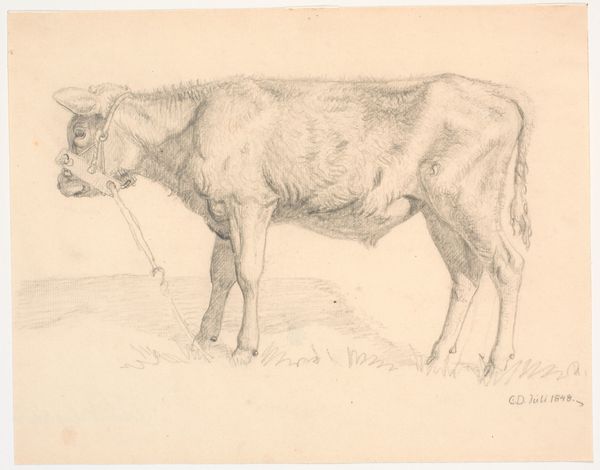

drawing, print, paper, pencil, graphite

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

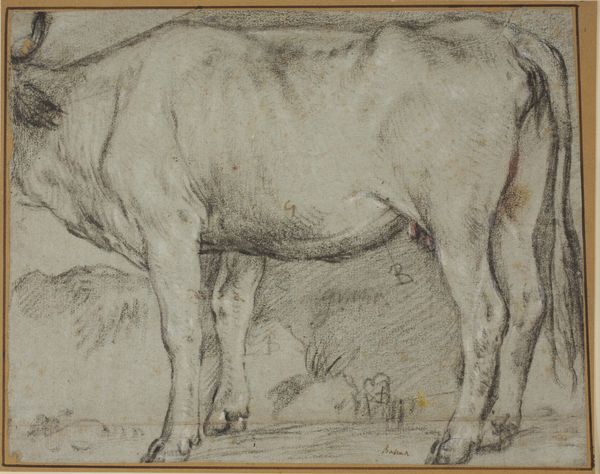

charcoal drawing

#

paper

#

form

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

line

#

graphite

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: 254 × 220 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

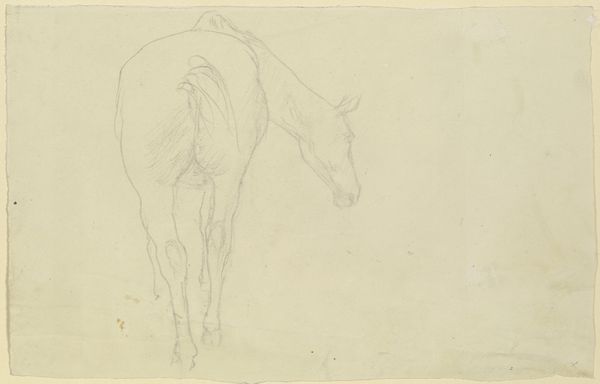

Curator: Here we have Théodore Géricault's "Standing Horse," a pencil drawing on paper created between 1818 and 1819. It resides here at The Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: The drawing feels so immediate. The tentative lines, the slight imperfections…it evokes a sense of searching for form, a study rather than a finished piece, imbuing the animal with a life that a more polished work might lack. Curator: Absolutely. Géricault was deeply invested in the representation of animals, particularly horses. Examining this through a lens of animal studies allows us to consider the shifting power dynamics between humans and animals in the 19th century. Equestrian culture was deeply entwined with aristocracy and military might. How might this study subvert, or perhaps reinforce, these established hierarchies? Editor: Well, looking at the horse itself, one can see the artist has given close attention to the animal’s musculature. This focus brings to mind the long cultural association between horses and freedom, virility and also classical depictions of power, like those of Roman emperors. The delicate rendering softens that power dynamic to my eyes, making the horse appear thoughtful. Curator: That’s a brilliant observation. Géricault was working in a period marked by significant social and political upheaval in France. His depictions of animals weren't just about capturing anatomical accuracy; they also reflected anxieties around power, control, and the changing social order. Consider his iconic "Raft of the Medusa" done during the same period where the animalistic nature of survival comes under scrutiny. Editor: I agree; the very act of sketching in pencil lends itself to capturing a fleeting, subjective experience. Here, we are not faced with idealized grandeur but with an honest encounter with the animal's physical presence. A very personal iconography arises from these simple tools. Curator: Exactly, and when viewing this sketch through a post-colonial framework, it challenges us to think about representation of non-human entities and the exploitation inherent in objectification and the social and cultural ramifications of equestrian tradition and how these practices relate to contemporary discourses of animal rights and liberation. Editor: Reflecting on our conversation, this seemingly simple sketch holds a mirror up to a lot of complexity, and that initial impression of immediacy speaks to Géricault's masterful translation of a centuries-long history between humans and animals, rendered visible on a single sheet of paper. Curator: And Géricault, through his focus, enables critical dialogues about how societal constructs can influence artistic depictions and ultimately shape cultural perception.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.