site-specific, wood, architecture

#

geometric

#

site-specific

#

architecture model

#

wood

#

architectural proposal

#

architecture

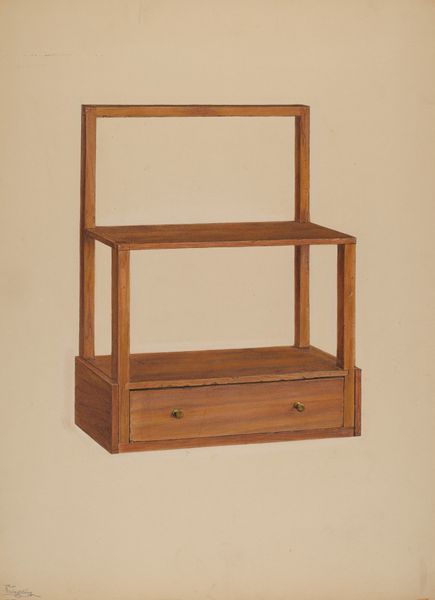

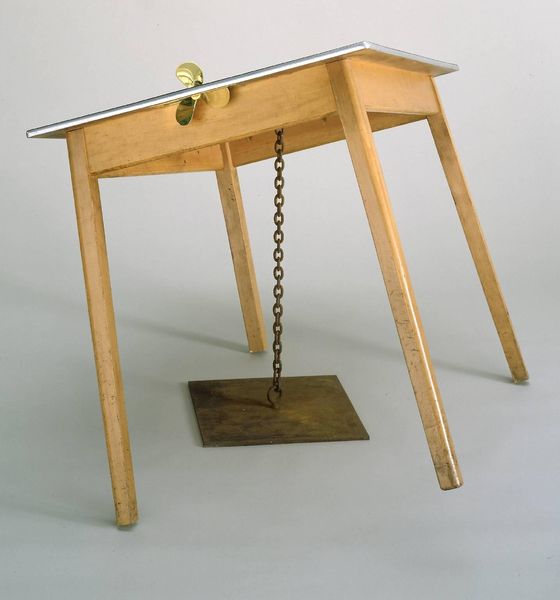

Dimensions: height 33.5 cm, width 33.6 cm, depth 33.5 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is the "Model of a Skylight," made in 1857 at Rijkswerf Vlissingen. The piece is primarily crafted from wood and serves as an architectural model. What’s your initial take on it? Editor: My first impression is one of quiet ingenuity. The model is so self-contained. There is such an attention to detail in the making and fabrication, which is wonderful. You can practically feel the craftsmanship imbued in it. Curator: Absolutely. When considering its time and place, we can see it as a reflection of 19th-century industrial ambition. These models are, on the one hand, representative of an optimistic relationship to naval design, and on the other, serve as symbols of empire-building. Editor: I see that. Focusing on the material, the choice of wood also highlights the ship-building industry's dependence on raw resources extracted and transported via trade routes, so we must think about what sort of exploitation went into constructing them. Curator: Right. Beyond material, it invites reflections on labor hierarchies inherent in its making. Who conceived it? Who executed the design? The piece operates within an established hierarchy, yet it presents itself humbly, almost anonymously. The way in which "craft" intersects with questions of class, empire, and innovation fascinates me. Editor: The joinery really commands my attention here; each piece fitting snugly into another through skilled carpentry and manufacturing. This wooden lattice embodies its purpose to let in light, yet here the materials are recontextualized. How else could it be repurposed? Curator: Its geometric clarity brings the dawn of modernism into sharp focus. A structure that’s ostensibly practical, can be viewed as art, demanding reflection of its original historical context, while serving a renewed function in the current museum space. Editor: The level of precision needed in crafting something like this highlights the immense labor input. Seeing it makes me wonder how this craftsmanship informed social relations within the Dutch dockyards. The act of creation and material manipulation should be discussed. Curator: Precisely, engaging with its physical presence alongside social context is indispensable. Ultimately, the artwork pushes us to examine how industry has always mediated identity, power, and meaning. Editor: Definitely. Seeing something like this prompts so many material inquiries and challenges about our presumptions and boundaries of artwork.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.