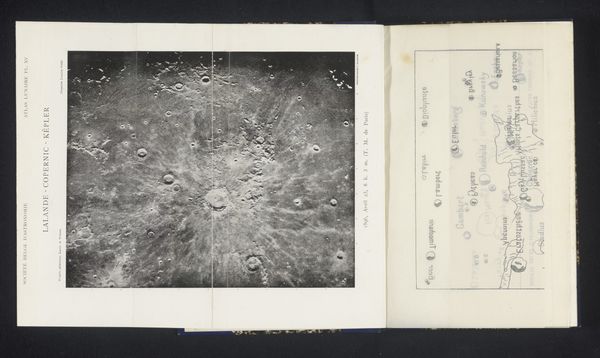

lithograph, print, photography

#

lithograph

# print

#

photography

#

geometric

Dimensions: height 228 mm, width 189 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

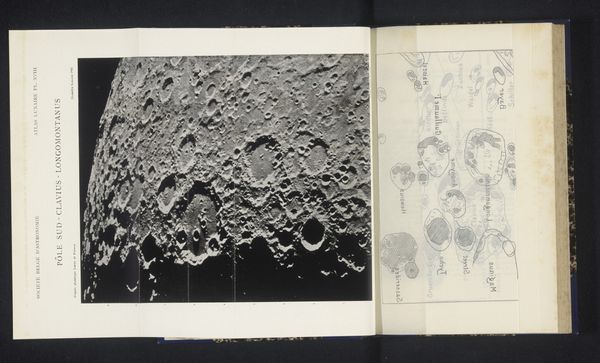

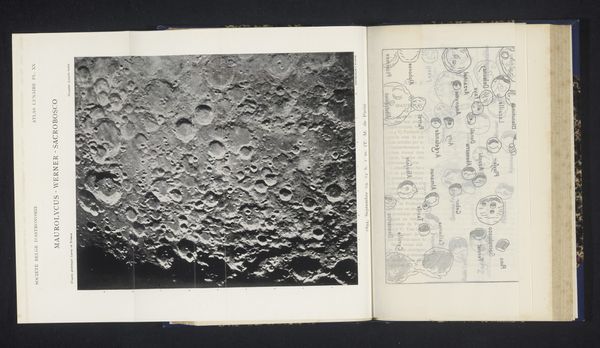

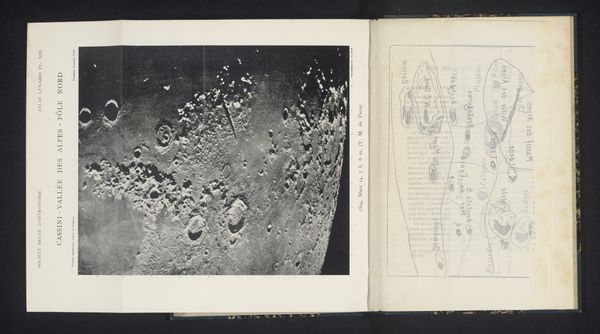

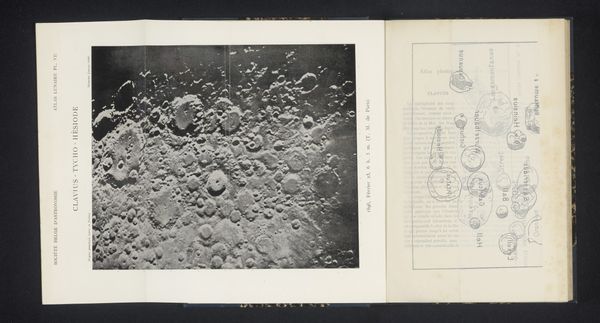

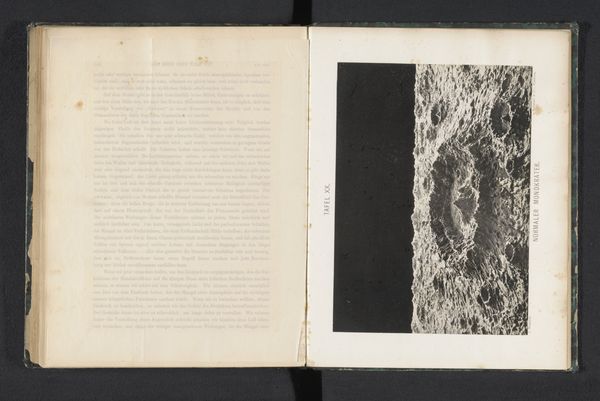

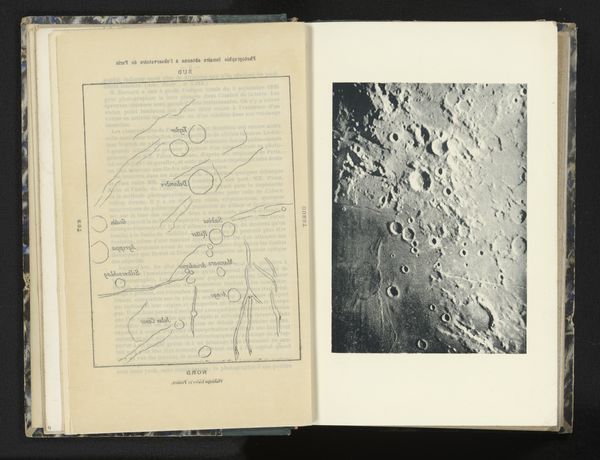

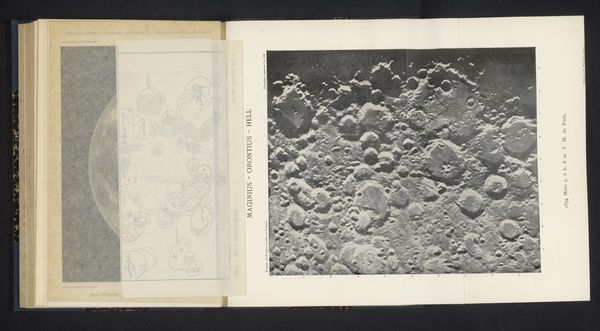

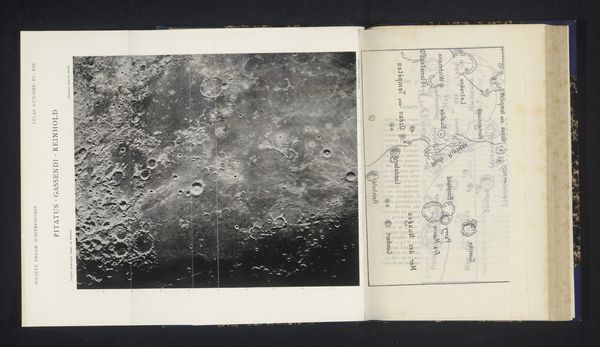

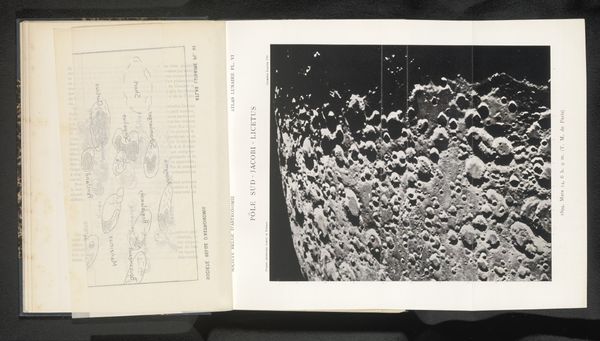

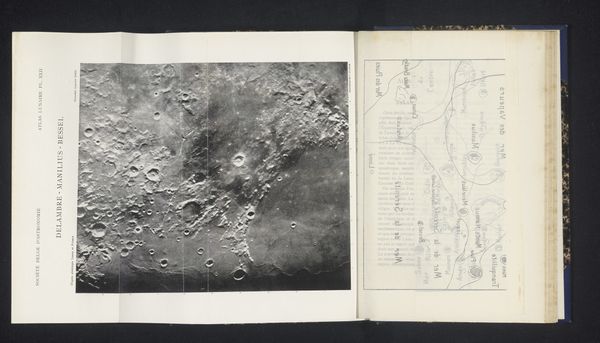

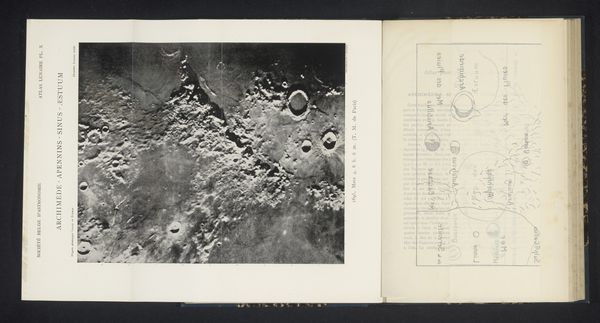

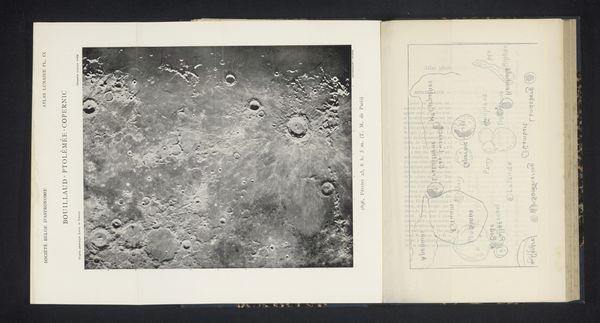

Curator: We’re looking at “Kraters op de maan,” or “Craters on the Moon,” by Loewy et Puiseux, created before 1899. It's a lithograph, but based on photographic methods. Quite striking. Editor: My initial reaction is, wow, that's a lot of texture! It's like a landscape, but alien and monochromatic. And seeing it as part of this bound collection, open like this, makes it so tactile. Curator: It really captures the shift in how we understand the cosmos, doesn't it? Photography allowed for a seemingly objective record of these celestial bodies. It moved astronomy away from pure speculation, anchoring it in the material world. Editor: Exactly. And think of the craft involved, translating a photograph into a lithograph. Someone meticulously etching that image, bridging scientific data with the artist’s labor. We easily forget how hands-on this kind of scientific representation was. Curator: These images became a public commodity. Consider its use—part of a larger atlas intended to popularize astronomy, to bring the heavens closer to everyday society. It really speaks to the cultural role of science in that era, an endeavor for a broad educated public. Editor: It brings to mind how our tools and processes of seeing constantly shape what we perceive to be true and natural. What did viewers in 1899, familiar with lithography, make of seeing this "photographic" image, especially since photographs were regarded differently back then, like reliable data? Curator: Precisely! This blend also mirrors a complex period in institutionalizing science, of needing credible images versus simply believing in speculation. Now a lot of what was perceived as "factual" then might be regarded differently now. Editor: It definitely shifts the discourse, making us look beyond the surface image, inviting us to really question the conditions of seeing. Thanks to this meticulous process, the moon becomes strangely more earthly, more connected to our lived reality through labor. Curator: It brings a wider historical context to what many might otherwise consider to be pure, objective science. Editor: And by recognizing its process, perhaps we can better view art as equally revealing of how labor makes both visible, and accessible, previously unknowable terrains.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.