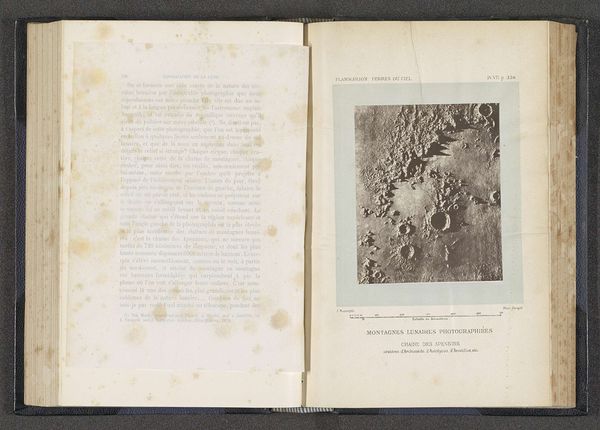

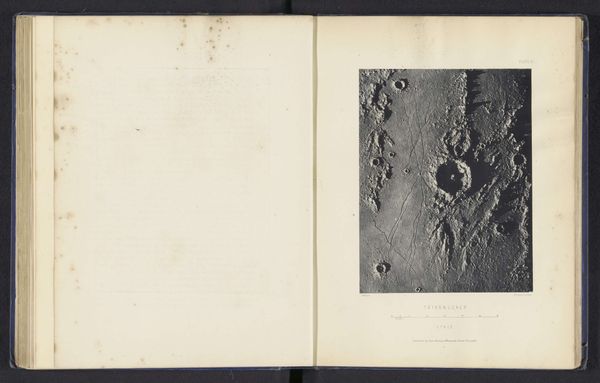

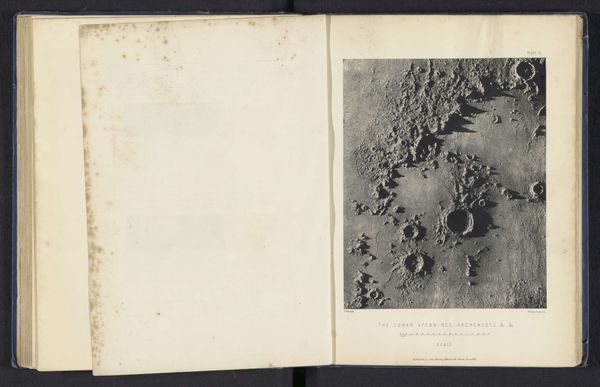

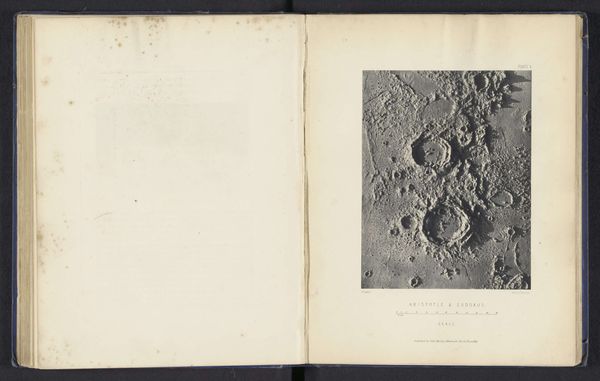

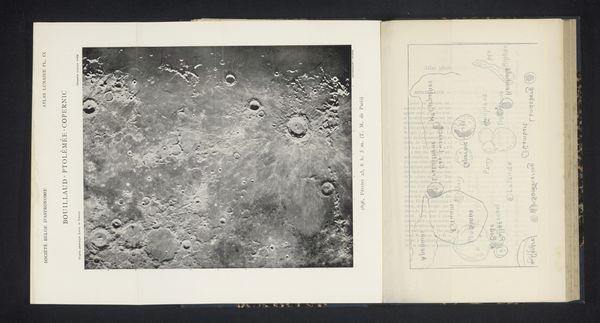

Gipsmodel van de maankraters Arzachel, Ptolemaeus en Alphonsus, van bovenaf gezien before 1873

0:00

0:00

jamesnasmyth

Rijksmuseum

print, photography, engraving

#

aged paper

#

homemade paper

#

paperlike

# print

#

typeface

#

landscape

#

paper texture

#

photography

#

fading type

#

geometric

#

folded paper

#

thick font

#

engraving

#

historical font

#

columned text

Dimensions: height 203 mm, width 147 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

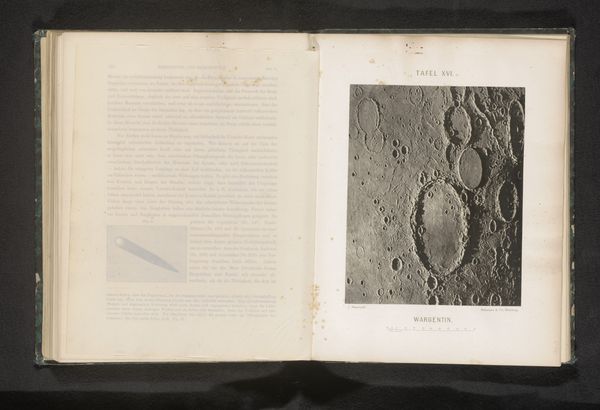

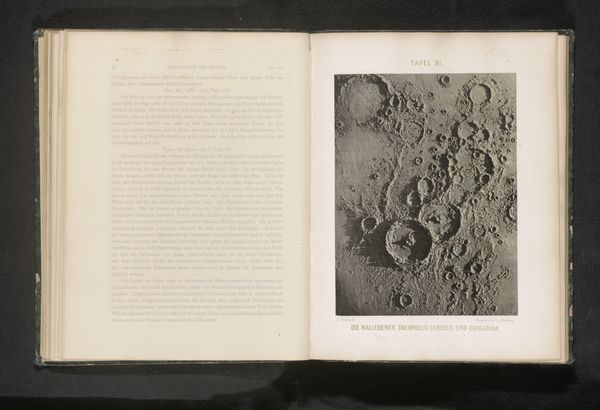

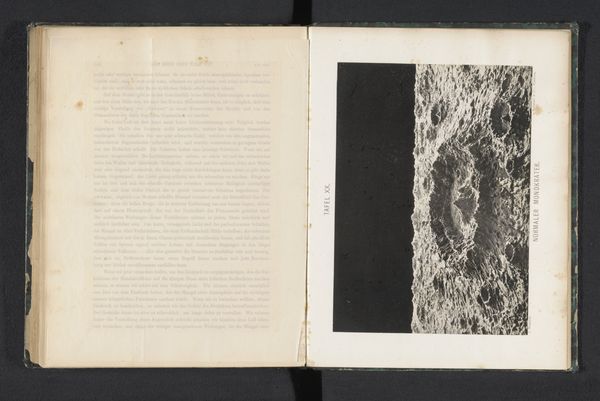

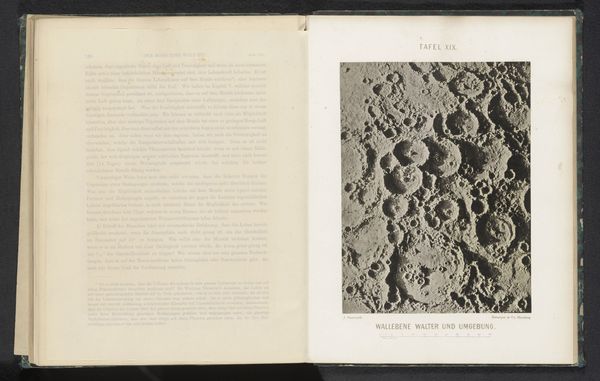

Curator: What an incredibly evocative image. Here we have James Nasmyth’s "Gipsmodel van de maankraters Arzachel, Ptolemaeus en Alphonsus, van bovenaf gezien," made before 1873. It’s held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The craters are powerfully rendered. They almost vibrate with an ancient energy, like scars of cosmic impacts permanently etched into the moon's surface. Curator: It’s important to note that this image isn’t a direct photograph of the moon. Nasmyth built a plaster model of the lunar surface based on telescopic observations, then photographed the model to create this print. Think about that, building a representation, rather than capturing the real thing. Editor: So it's not just about craters; it's about representation. It speaks to the limits of what could be visually known and recorded at the time, particularly through the lens of imperial science. This was a period deeply invested in classification and domination through knowledge. But how reliable is this reproduction? What is gained, or lost, in the process of re-presentation? The scientific process cannot be separate from the colonial context. Curator: It raises fascinating questions about visual knowledge and the role of artistic interpretation within scientific inquiry. But consider too how those deep craters take on metaphorical significance when juxtaposed with human-inflicted traumas? What collective traumas might be mirrored in the violent origins suggested by the landscape of the moon itself? Editor: Definitely. And the act of translating celestial bodies into tactile models for study raises questions of accessibility, particularly within the educational models of the late 19th century. Was it presented to foster public knowledge of astronomy, and whose public would be given access? What were its cultural and perhaps also class uses? Curator: Looking closely, I think the rough paper adds a vital textural element. This, coupled with its monochrome palette, creates a powerful atmosphere that emphasizes form and depth and gives insight into not just how knowledge of the world can be portrayed but how it should be represented, interpreted, and therefore understood. Editor: Exactly. Thank you. I’ve gained such insight into the layers of cultural meanings this evokes when viewing an image of craters. Curator: Indeed, a very impactful image, full of fascinating contradictions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.