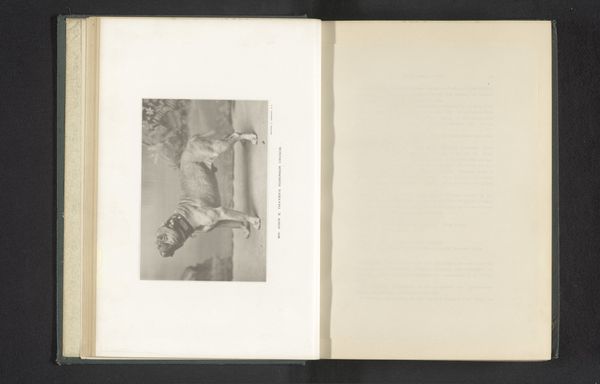

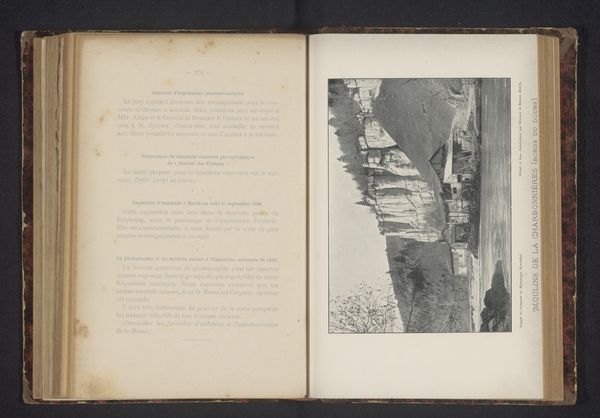

print, photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

# print

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

#

genre-painting

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 181 mm, width 119 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

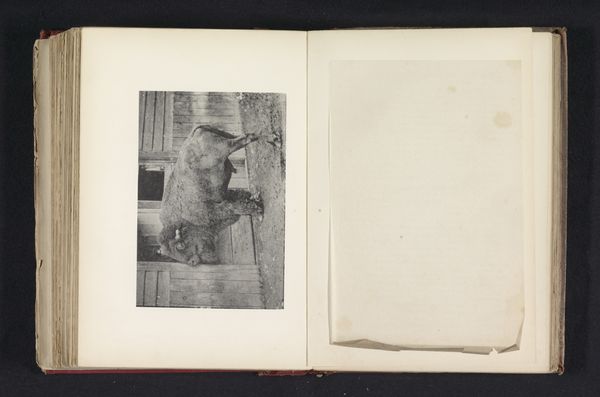

Curator: Here we have an albumen print from before 1894 by George Wolf entitled, "Plaat met twee afbeeldingen van een circusolifant met zijn verzorger," which translates to "Plate with two images of a circus elephant with its caretaker." Editor: The light is fantastic; I'm immediately drawn to the elephant’s textural skin, rendered in striking detail through the photographic print process, while there’s such a strong sense of enclosure within a constructed space. Curator: Precisely! The albumen print was hugely popular in the late 19th century, becoming synonymous with scientific and documentary photography, a rising tool utilized to catalog expanding colonial menageries. These photographic methods shifted what and how we deemed something "art". The very mass production, even the *idea* of the print becomes integral to its message. Editor: Yes, there is an undeniable power in repetition; each print can then perform its specific duty, each existing and serving differently to diverse audiences across geographic regions, making accessible that which one might never witness firsthand. Curator: Indeed! Also note the compositional structure, wherein two separate frames appear. We can explore both its performative circus aspect alongside the intimate relationship between animal and human caretaker, creating a strange dependency inherent to colonial enterprises. It underscores that zoos and menageries were places of spectacle *and* scientific inquiry. Editor: I’m very sensitive to that notion of dependency. Albumen printing demanded great technical skill involving multiple processes. The availability and accessibility of specific papers, silver nitrates, and light influenced its entire image-making. Every element of material production affects meaning. Curator: Precisely! The making process also became inextricably bound to evolving societal narratives centered around exoticized representation during expanding colonial power dynamics! What lingers most prominently are all these complex social implications about humans' relations to other beings. Editor: It underscores then how images are actively produced through specific material circumstances *and* historical social contexts, requiring our analysis, not mere aesthetic enjoyment. Curator: Absolutely, a historical photograph asks us not just to see, but to consider how the act of seeing itself is shaped. Editor: I will certainly keep that in mind!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.