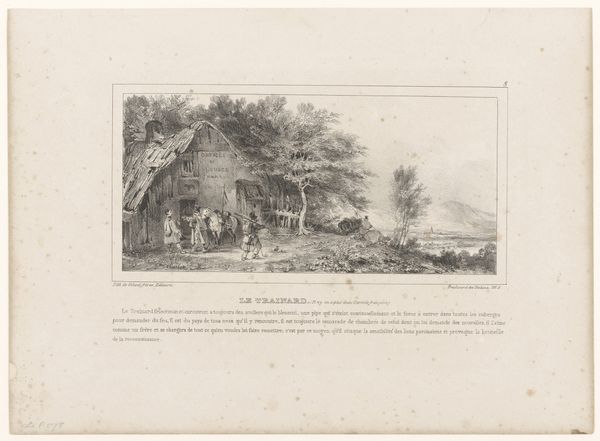

print, engraving

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

landscape

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 443 mm, width 553 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What strikes me first is the serene, almost idealized, quality of this scene, even though the men are actively preparing to hunt. There's a tension there. Editor: Indeed. This is "Twee jagers maken hun geweer schoon," or "Two Hunters Cleaning Their Guns," a print possibly from 1769, now held at the Rijksmuseum. The engraver was William Woollett. It speaks volumes about leisure, labor, and class dynamics of that era. The medium, engraving, tells a crucial story itself. Curator: Absolutely. Engraving requires a mastery of tools and meticulous process – think of the labor and the highly developed skill needed. These prints circulated widely, influencing perceptions of the English countryside and its inhabitants. How do we see that reflected here? Editor: Note the setting. We're not in a wild, untamed landscape, but rather one carefully managed and cultivated. The two men, presumably gentlemen hunters based on their attire, are attended by dogs. This wasn't about sustenance. Hunting was very performative and restricted along social strata. Consider who had access to the means of production to shape these visual narratives. Curator: Right. The social context is clear. These hunting scenes were produced, consumed, and controlled by an elite demographic. And the visual vocabulary is worth mentioning: landscape, genre painting, academic art -- each with its own codes. Did you notice how the natural environment dwarfs the working men, literally placing labor in subordination to both class and natural production? Editor: I find myself considering its impact on broader notions of masculinity and dominance. How does this image naturalize hierarchies? It presents a specific, arguably romanticized, view of rural life that served specific interests. Who owned the land? Who benefitted from hunting? Who cleaned the guns, really? Curator: Precisely. This print serves as propaganda, but it's crucial to understand the mechanics and networks that supported these forms of imagery. Editor: So when we view the natural setting, which is pretty indeed, we ought to bring the material world into sharper focus: consider who produced the work, and how class and social power influenced how the image came to be produced and circulate. Curator: Well, thank you; this exploration of context adds new layers to this work and broadens my insight of Woollett and how his engravings operated within specific socio-economic and aesthetic structures of 18th-century print culture. Editor: It also speaks to art history's potential for fostering dialogue, so as we revisit such landscapes, we remain cognizant of how narratives intersect with reality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.