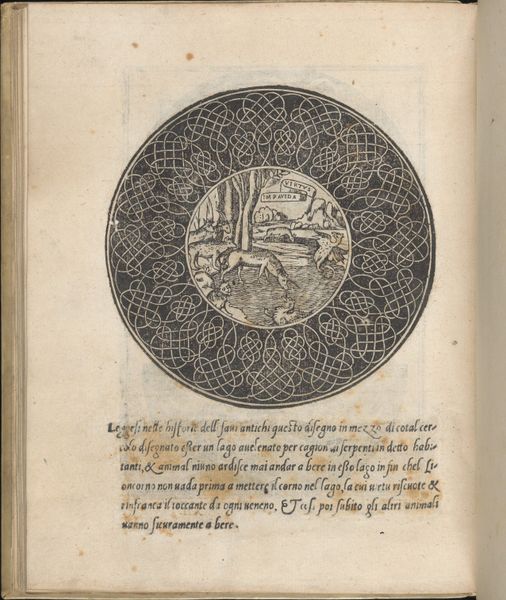

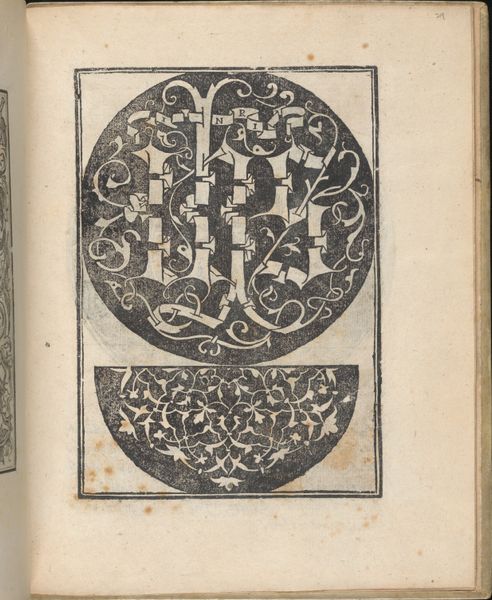

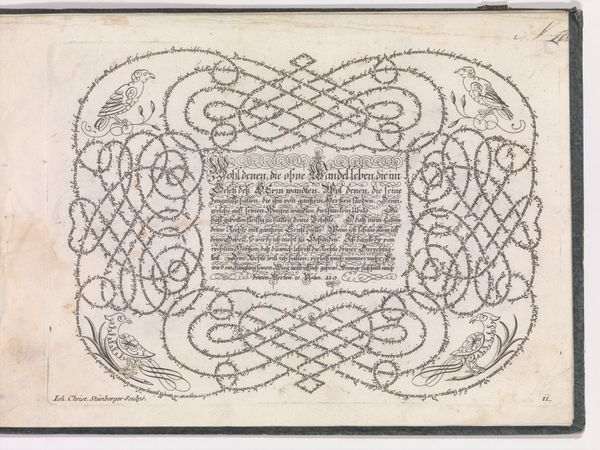

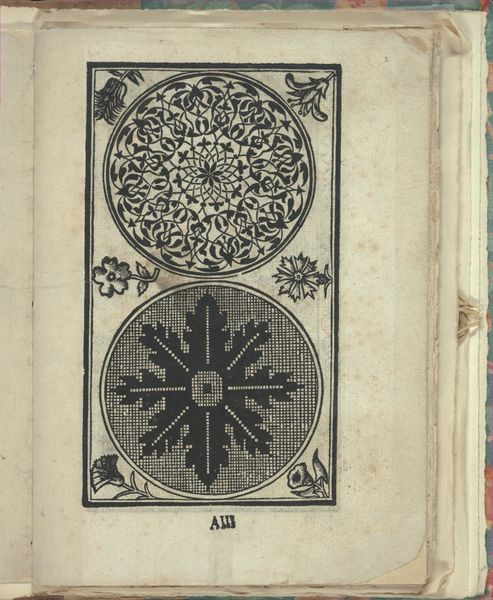

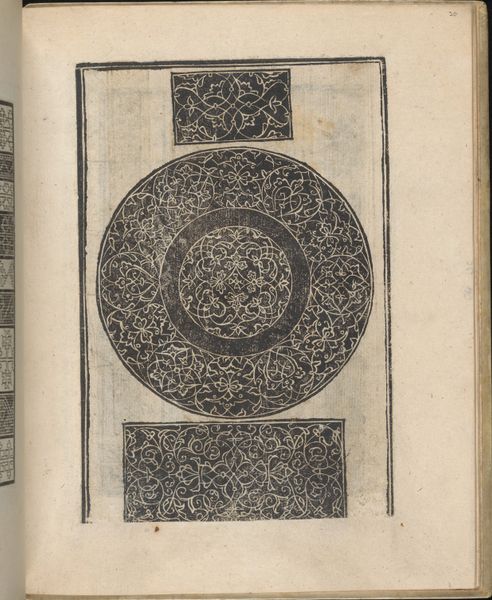

drawing, coloured-pencil, print, intaglio, engraving

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

# print

#

book

#

intaglio

#

sketch book

#

personal sketchbook

#

coloured pencil

#

geometric

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: Overall: 7 13/16 x 6 3/16 x 3/8 in. (19.8 x 15.7 x 1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Take a moment to consider this page from "Essempio di recammi," dating back to 1530, conceived by Giovanni Antonio Tagliente. Crafted using intaglio, engraving, drawing, and coloured pencil, it now resides at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. My immediate reaction is one of visual intricacy – the interweaving circular border draws my eye right into the allegorical scene within. What catches your attention? Editor: Immediately, the central image suggests a commentary on power dynamics, doesn’t it? You see the other animals seemingly deterred from approaching what looks like a poisoned watering hole and only the animal with the horn appears to know of it’s saving grace: by first touching it to the water it can drink without the threat of illness, almost like a test of courage before life's necessities. But how does it connect with contemporary society back then? Curator: The symbolic narrative touches upon fundamental virtues and societal apprehensions. “Virtus Impavida” reads the banner. What do you make of this specific word? Editor: "Virtus Impavida" – Intrepid virtue or Courageous Virtue. Implying the brave and righteous. With the cultural context in mind, these symbols could be tied to the concept of virtuous rule or the triumph of justice during that specific tumultuous time. Given the early 16th century context of the artwork, perhaps the symbolism is about holding on to one’s power? Curator: Indeed, Tagliente, known for his books on calligraphy and embroidery patterns, embedded more than just mere design. This particular page acts as a moral lesson disguised within the guise of a decorative pattern. We could perhaps infer that the complex geometric shapes serve not just an aesthetic purpose, but as an encoded representation of moral structure. Editor: And the use of what looks to be like coloured pencil makes me wonder, to what degree these early pattern books acted almost as ‘personal sketchbooks’ where the artisans freely developed these complex pattern relationships to each other? Curator: That’s certainly something to ponder. Tagliente gives us a multi-layered commentary of society's moral fibres during the renaissance period, but with that, also a small personal artistic experiment with visual balance, and use of colours in the rendering of his allegory. Editor: And seeing this intricate visual reminds us that even something intended for practical use can embody potent messages and enduring artistic flair, regardless of the intention, giving the image it’s cultural longevity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.