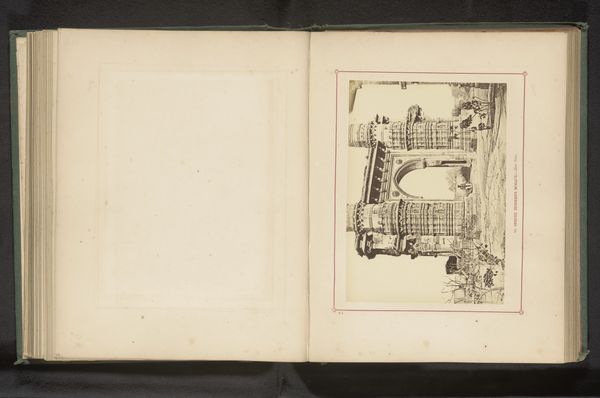

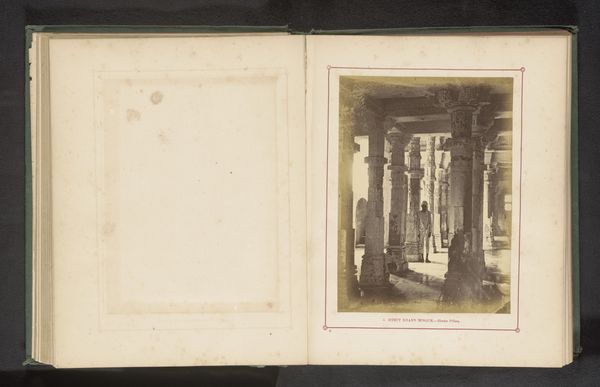

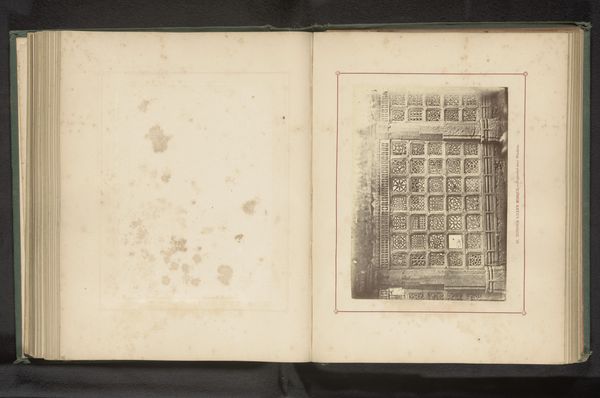

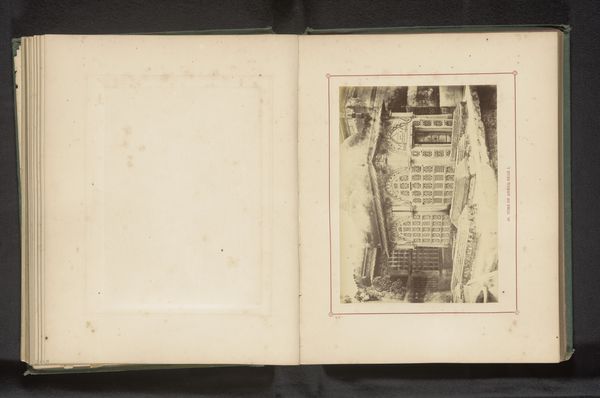

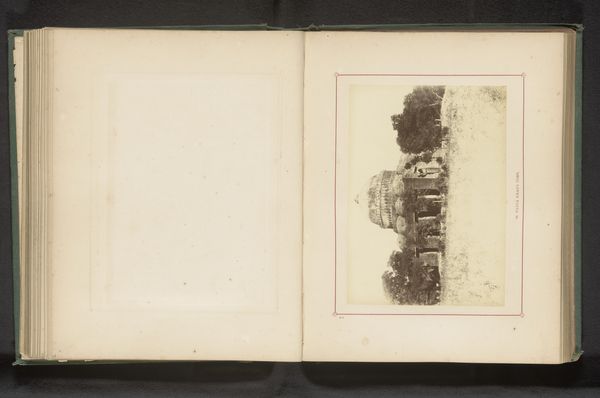

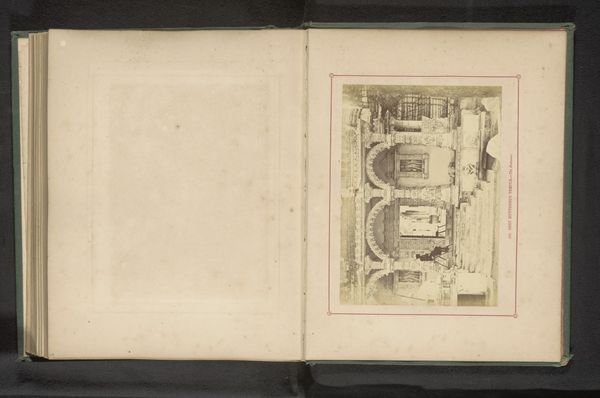

print, photography, albumen-print

# print

#

perspective

#

photography

#

cityscape

#

islamic-art

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 135 mm, width 186 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We're looking at "Zuilengalerij van de Dastur Khan-moskee in Ahmedabad," an albumen print, so photography really, taken before 1866 by Thomas Biggs. It offers a fascinating glimpse into 19th-century Islamic architecture. Editor: It's sepia-toned, incredibly detailed... there’s almost a weight to it, despite it being an image. All those lines of the pillars converging, they make me feel like I'm being pulled in, not just visually, but into another time, another cultural context. Curator: Exactly, and this perspective wasn’t accidental. Photography in this era, especially colonial photography, played a role in shaping perceptions of other cultures. The strategic composition, emphasizing architectural grandeur, often reinforced power dynamics. Editor: So, even in an seemingly objective depiction of architecture, there's an underlying agenda? Is it attempting to "capture" or even, control through representation, the narrative of Islamic spaces and communities? Curator: I would argue, at least partially. Think about the context—British colonial rule in India. Photography becomes a tool for documentation but also for projecting an image, framing a narrative suitable for a European audience, one which tacitly reinforces a sense of Western superiority. Editor: I can see that. But I’m also struck by the human element within this imposing structure. There's someone within the archway, small against the massive pillars and intricate designs. Is that person's inclusion a conscious counter-narrative? Or just a record of a presence in that particular moment? Curator: A complex question. The human figure adds a scale and an element of everyday life but within a carefully constructed frame. The composition isn’t egalitarian. What purpose does including that one small figure serve? It isn't empowering them; on the contrary, that presence reinforces a sense of architectural vastness that inherently makes a human feel inconsequential by comparison. Editor: This makes you consider the silent conversations happening in photographs like this one... what they reveal, but perhaps more critically, what remains hidden, or skewed by the lens and the perspective of the one holding the camera. Curator: Absolutely. It encourages critical examination. Recognizing that photos, prints and other forms of documentation aren’t neutral—they carry social and historical baggage that is just as interesting and illuminating. Editor: I am left contemplating this image not just as a piece of art or historical documentation, but as an object deeply implicated within broader structures of power and representation. Curator: And by recognizing these complex layers, hopefully we are creating a deeper understanding and more equitable dialogue regarding cultures and communities around the world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.