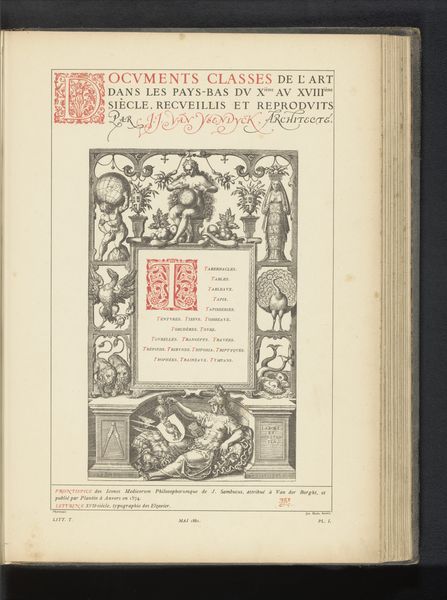

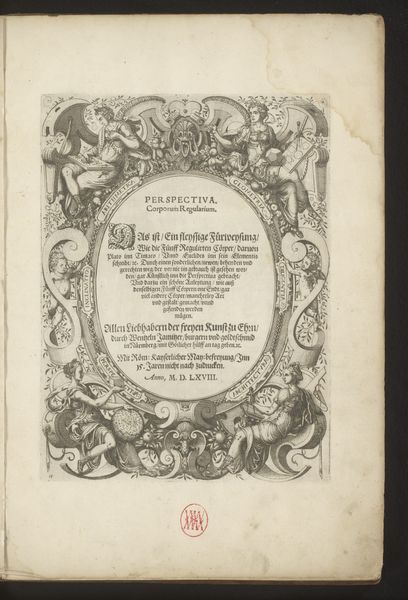

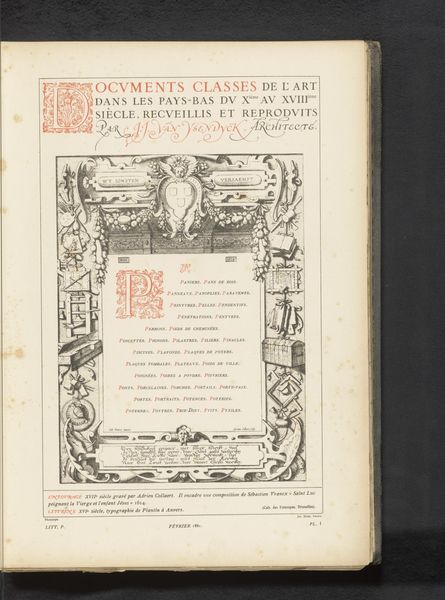

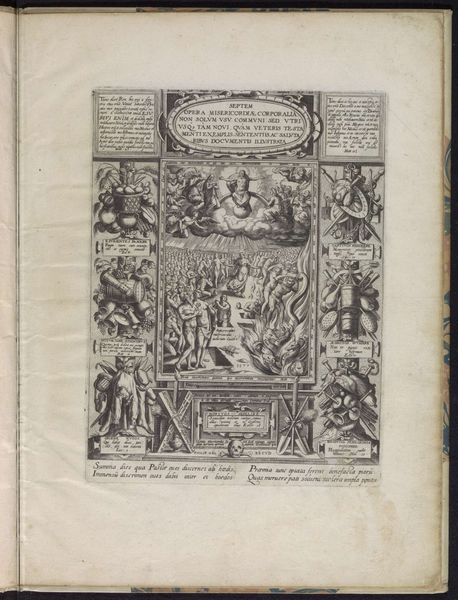

Reproductie van een titelpagina uit het Theatrum orbis Terrarum van Abraham Ortelius, met Jupiter, Juno, Neptunus en andere figuren before 1880

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 350 mm, width 232 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a reproduction of a title page from Abraham Ortelius's *Theatrum Orbis Terrarum*, placing it before 1880. It’s a print, possibly an engraving on metal and paper, full of allegorical figures in that grandiose Baroque style. It feels very constructed and consciously assembled, like a statement of power. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a highly constructed object, not just in its imagery, but in its very being. It’s crucial to understand that printmaking was a form of industrial production. This wasn't just art, it was a commodity, produced en masse and distributed widely. Look at the detail, consider the labour involved in creating the plate, the cost of materials. These aren't simply aesthetic choices; they reflect the economic realities of the time. The figuration tells us something about status too. Editor: So you’re saying the content is less important than how it was made and who consumed it? Curator: Precisely! Who had access to this information, to these maps? Who benefited from this visual representation of the world? Think about the colonial implications embedded in representing and mapping territories. The choice of metal engraving is also key - its ability to be reproduced is crucial for circulation. Editor: That really makes you think about how maps weren't just objective representations but active participants in shaping global power structures. Curator: Absolutely. It’s a process, a system, all these stages of crafting this object, each embedding different ideologies of labor, value and how information is controlled. Editor: I hadn’t really considered the production process so directly before. This really changes how I see the piece. Curator: Indeed! Focusing on materials helps deconstruct the authority these images claim.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.