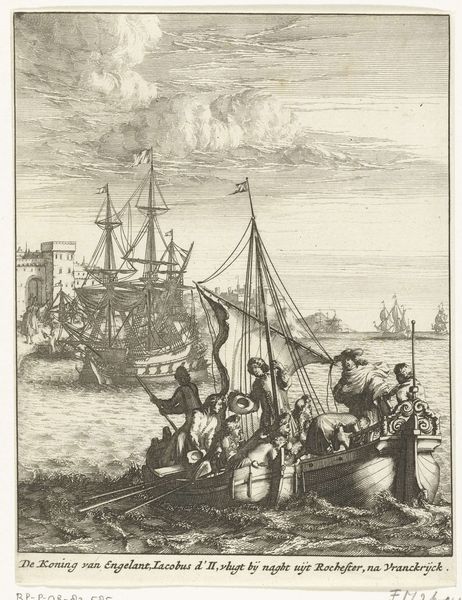

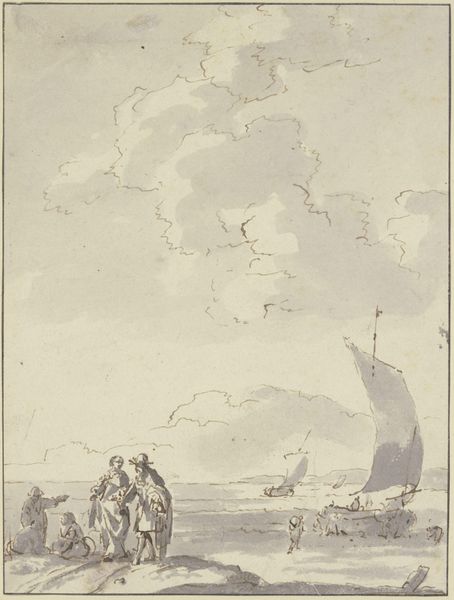

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 190 mm, width 141 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: It's almost theatrical, this scene—the dramatic fire, the ships on the horizon... Editor: You're right, the artist here is Arnold Houbraken, and we are viewing his engraving "Onthoofde lijk van Pompeius verbrand," created sometime between 1681 and 1699. The print depicts the aftermath of Pompey's assassination. Curator: An engraving? I can see the texture of the paper almost adding to the grim atmosphere. There's something very physical about it. Like an eyewitness account rendered with incredible immediacy through simple ink and skilled labor. Editor: Indeed. It captures a historical moment fraught with significance. Note the figure holding Pompey's severed head – the ultimate symbol of defeat and betrayal. Consider how that symbol resonated in the tumultuous political landscape of the 17th century, riddled with conflict and ambition. It's not just a depiction, it's a warning, an examination of power's transience. Curator: The flame dominates. Death and purification through fire—the phoenix rising from the ashes is always tempting, though the narrative Houbraken presents is purely death. Burning, quite viscerally, any claim of earthly remains to sanctify. But, what’s fascinating is that he doesn't make it overtly sensational. There's a restraint, a sense of reportage despite the evident spectacle of burning the body of a beheaded General. Editor: Absolutely. The details speak volumes, don't they? From the plumes of smoke to the tools used in crafting the engraving. One could explore, for example, the etchants used for the various elements—deliberate crafting with mordants that reflect the deliberate machinations surrounding the scene in its portrayal. Houbraken really showcases an acute awareness of materials transforming history itself. The tools employed, the acid's bite upon the plate – echoing, perhaps, the metaphorical acids dissolving reputations and empires. It really brings into relief a rather sober meditation on the human condition. Curator: Ultimately, there is a stark dichotomy. Death being played out very privately with large events occurring just out of immediate sight, implying a kind of infinite space beyond the figures. It asks if perhaps it's better to remain unenlightened about the violence just out of frame. Editor: And seeing how it's done through engraving reminds us of how information, propaganda, and versions of "truth" get distributed. In this age, we often consider that alongside questions of truth and history too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.