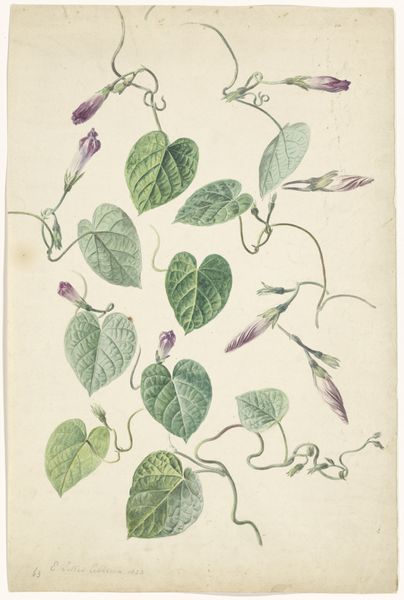

drawing, print, watercolor

#

drawing

#

water colours

# print

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

botanical art

#

realism

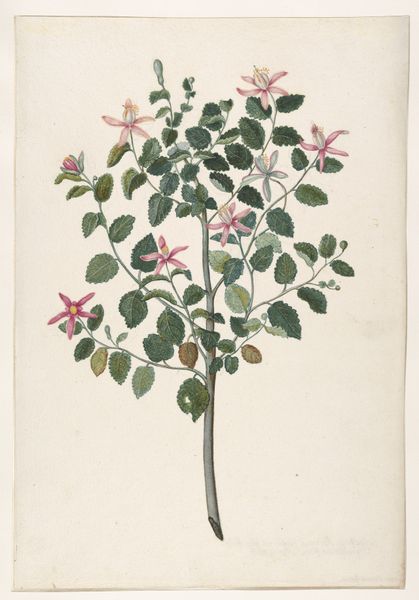

Dimensions: 16 1/2 x 10 in. (41.91 x 25.4 cm) (plate)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have James Sowerby’s "Pergularia odoratissima," also known as the Chinese Creeper, a watercolor drawing and print from 1793. It feels very precise and scientific in its rendering, almost like an objective record. How would you interpret this work, looking at it through a historical lens? Curator: That precision you note is key. Botanical illustrations like this, especially in the late 18th century, played a significant role in the expanding global project of colonialism and scientific cataloging. It's not simply about accurately depicting a plant. Editor: Oh, really? In what way? Curator: Think about it. Europe was hungry for resources and knowledge from around the world. Botanical illustrations were crucial tools. They allowed scientists and traders back home to identify, classify, and potentially exploit plants found in newly "discovered" lands. Editor: So this image has political undertones? Curator: Absolutely. Images like this one, seemingly innocent depictions of nature, were deeply embedded in systems of power and resource extraction. The 'objectivity' we see is part of that scientific, colonizing gaze. Consider the plant itself; "Chinese Creeper," is being labeled and categorized within a European framework. Editor: That's fascinating! I never considered the act of documenting nature as having a political dimension. Curator: It's a reminder that art, even scientific illustration, isn't created in a vacuum. Examining its historical context reveals the social and political forces at play. It certainly reframes how we see a piece like this, doesn’t it? Editor: It completely does. Thanks, I have a new appreciation for what this represents.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.