Familiealbum met foto's van een familie in de voormalige kolonie Nederlands-Indië en van een suikerfabriek in Purworejo c. 1916 - 1930

diversevervaardigers

Rijksmuseum

photography, gelatin-silver-print

portrait

photography

historical photography

group-portraits

orientalism

gelatin-silver-print

realism

Dimensions: height 375 mm, width 278 mm, width 560 mm, thickness 40 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

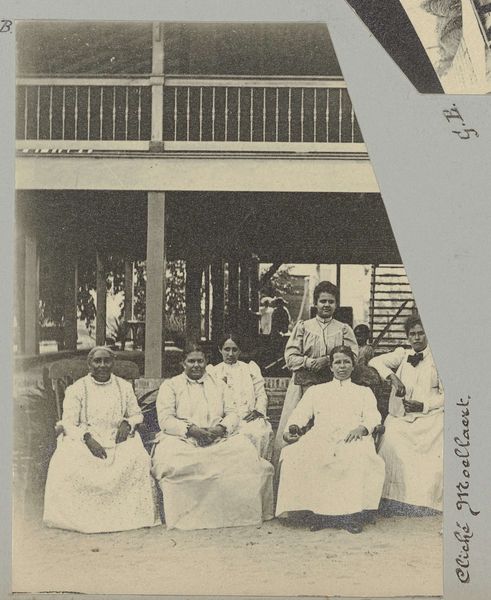

Curator: Let’s consider this intriguing gelatin-silver print from the early 20th century, dating roughly between 1916 and 1930. The Rijksmuseum holds it within its collection. It's an album page featuring a family portrait set against the backdrop of a sugar factory in Purworejo, then part of the Dutch East Indies. Editor: The uniformity is striking. Everyone’s dressed in white, arranged with almost military precision in front of a grand colonial building. There is something unsettling, almost eerie, about this rigid display. Curator: Indeed. These studio photographs were a significant cultural tool. Albums like these documented colonial life and social structures. This image, in particular, shows a visual power dynamic inherent in the colonial project. Note the specific setting: a sugar factory. This links family identity and pride directly to a global commodity flow fueled by exploited labor. The immaculate white clothing and stiff poses denote not only social status but also a projection of European control. Editor: And look at the implicit hierarchy—the separation between the seated children and the standing adults, the clear differentiation of dress and even skin tones hint at deeply ingrained social divisions reinforced and maintained through images like these. Consider the cost of photography at the time. These were constructed representations accessible to very few. Curator: Exactly! And the gelatin-silver process itself tells a story. Its wide adoption enabled mass reproduction and distribution of such imagery, solidifying the visual vocabulary of colonialism and orientalism. What's also fascinating is that these photo albums themselves were commodities that were then circulated and consumed. This image becomes evidence of cultural consumption and labor practices entangled in the photographic material. Editor: So it’s not simply a family photo, but a crafted artifact representing the power dynamics and social ambitions of its time. It challenges us to reconsider the photographic medium as both a reflection of reality and a tool in shaping it. I see this album as evidence—evidence of a complex socio-political interplay captured on a single gelatin-silver print. Curator: Precisely. Examining this image has deepened our understanding of photographic materiality, colonial enterprises, and the historical and institutional narratives that museums like the Rijksmuseum continue to construct around them.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.