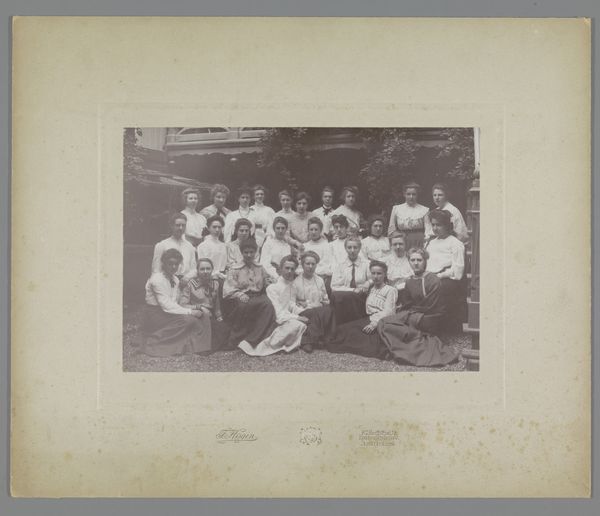

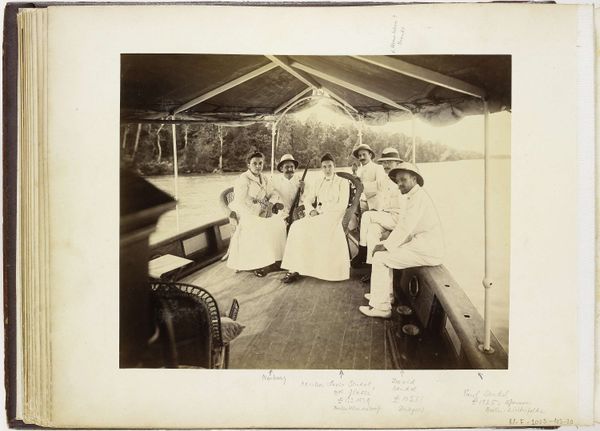

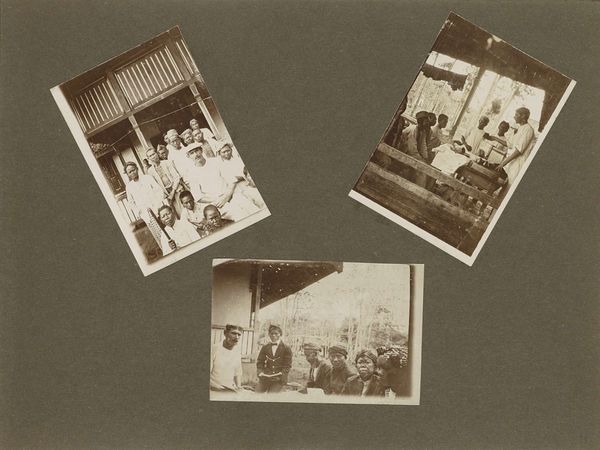

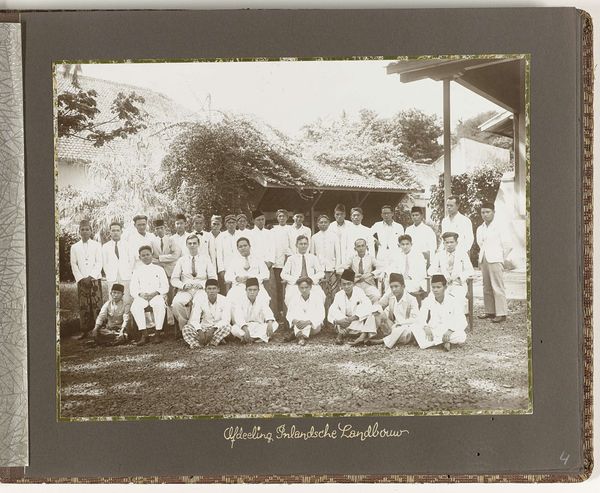

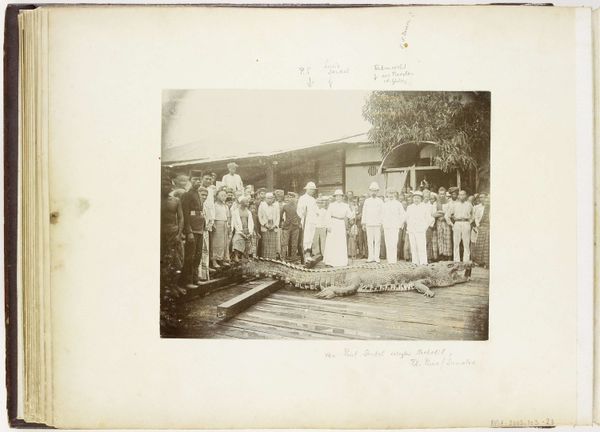

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

group-portraits

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

modernism

#

realism

Dimensions: height 228 mm, width 287 mm, height 355 mm, width 453 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a photograph titled "Portret van familie Boers met personeel," created in 1919. It's a gelatin silver print. It's a rather formal group portrait, but the stark contrast between the family and their staff is quite striking. How do you interpret this work, considering its historical context? Curator: This photograph provides a window into the power dynamics inherent in colonial societies. The family, likely of Dutch descent, is posed prominently, while the “personeel,” the staff, are arranged in a way that subtly emphasizes their subordinate position. Consider the historical moment—1919. What societal structures were in place that normalized such visual representation? Editor: It's interesting that you mention power dynamics. The all-white clothing seems to reinforce that, especially considering that it probably wasn’t easy to keep such garments clean. Is there a deliberate statement about privilege being made here? Curator: Precisely. The choice of clothing, the setting, the very act of commissioning a photograph—all speak to a specific class and racial hierarchy. It’s vital to dissect the photographic representation and what is not being represented. Think about what voices are absent from this picture and why. Whose narrative is being prioritized, and at whose expense? Editor: That’s a perspective I hadn't fully considered. So, seeing this portrait not just as a family photo but as a statement on colonial power structures? Curator: Exactly. And it encourages us to critically examine the visual rhetoric employed to legitimize such structures. What responsibility do we, as viewers, have when engaging with images like these? How can we use them to challenge the legacies of colonialism rather than perpetuate them? Editor: I learned to read beyond the surface, seeing how an image, seemingly straightforward, can be loaded with social and historical meaning. Curator: Yes, and remember, our interpretations are never neutral. By asking difficult questions about identity, representation, and power, we can strive to create a more just and equitable understanding of our past and present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.