lithograph, print

#

narrative-art

#

lithograph

# print

#

caricature

#

history-painting

#

realism

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

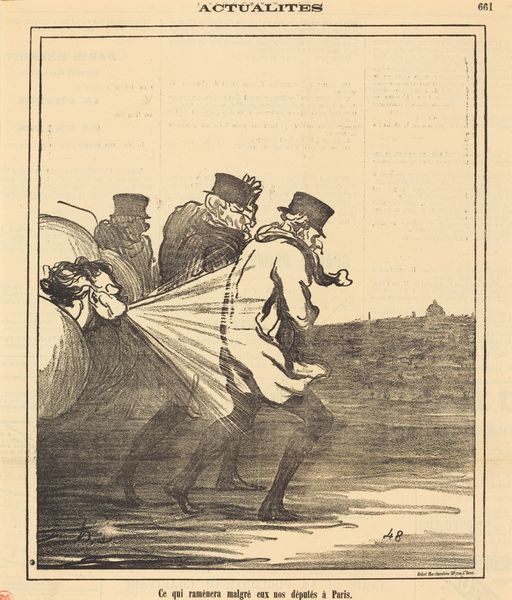

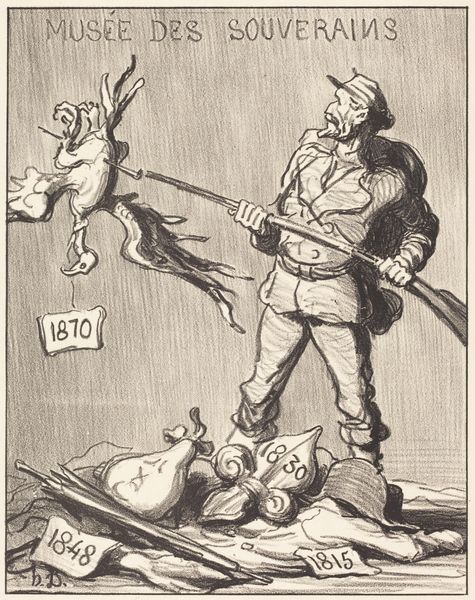

Curator: Daumier's lithograph, "Déjà relevée!", made in 1871, depicts a potent scene of post-Franco-Prussian War France. There’s a starkness to the greyscale lithography, isn't there? The immediate feeling is bleak. Editor: Indeed, the high contrast emphasizes the weight of the historical moment. But tell me more about Daumier's method of production at the time? What sort of tools and workshops would he have been employing? Curator: Daumier, prolific as ever, worked quickly to produce images for publications like “Actualités.” The process involves drawing on lithographic stone, which is then treated with chemicals, inked, and printed. This method enabled a mass production of imagery that was vital for social commentary, allowing his art to rapidly circulate and directly engage with contemporary issues. Editor: Which is deeply relevant. What social critiques does it offer, do you think? Because, to me, this lithograph reads as a commentary on the burden of war debt. You see France, personified by a statuesque figure of a woman, leaning on a large sphere labeled "Emprunt" – Loan. Below her are caricatured figures, clearly representing the French populace, looking up with a mixture of anxiety and resignation. It’s incredibly sobering, really emphasizing the unequal impact war had on all classes. Curator: Precisely. Consider also that printmaking during this period also became a vital, sometimes subversive, form of artistic and political expression during periods of intense state censorship in France. Lithographs are fascinating historical artifacts documenting both a nation's and individual's struggles. But, in relation to these people represented, what roles do they assume in the process of production itself? How is the art consumed and distributed among them? Editor: Yes, excellent point! And here, Daumier is definitely implicating those masses into an awareness of the mechanisms and financial implications of defeat and recovery. There is also a great commentary on gender, right? The representation of France as feminine and burdened reinforces patriarchal notions of nationhood while simultaneously critiquing the weight placed upon the country. Curator: Looking at it this way provides some context for thinking of the distribution process too—to better comprehend how many lithographs were consumed. Perhaps now the labor behind such works can be brought to light as well. Editor: It reminds us that art isn’t just a beautiful object, but a historical document shaped by production methods, shaped by the politics, anxieties, and hopes of its time. A truly sobering reminder that we must continue questioning these power structures even now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.