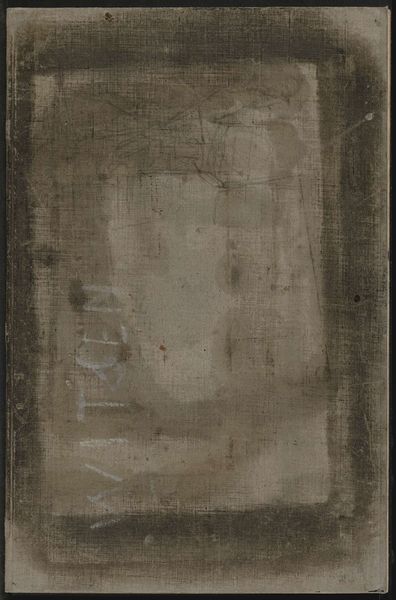

print, daguerreotype, paper, photography

# print

#

daguerreotype

#

paper

#

photography

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 14 × 11.5 cm (image/paper)

Copyright: Public Domain

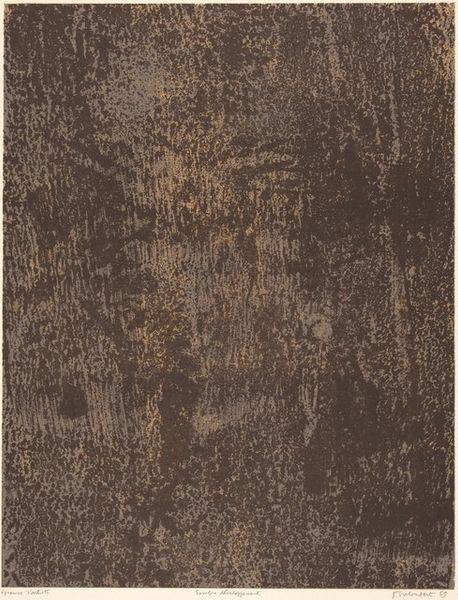

Curator: What an intriguing piece. Before us we have William Henry Fox Talbot’s "Botanical Specimen," circa 1835, housed here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Created using, as the artist would dub it, “photogenic drawing” on paper. Editor: It strikes me as hauntingly ethereal, almost ghost-like. The muted greys and whites lend it a dreamlike quality. Is that the plant itself, or some kind of negative impression? Curator: Indeed. Talbot's method involved placing botanical samples directly onto light-sensitive paper. Where the light couldn’t reach, the paper remained white; where it could, it darkened, creating what we now call a photogram. We need to remember this was revolutionary for the time; he's essentially writing with light, recording the presence of these specimens. Editor: That ghostly, fragile quality then is the real subject matter here. Botanical imagery often evokes cycles of life, but this almost presents them as disappearing. Was there a political context at play? Were anxieties about environmental changes manifesting this way? Curator: I believe so. The Industrial Revolution was well underway, altering landscapes and communities, especially the land and the poor who toiled in the land. There's perhaps a longing to preserve something precious before it vanishes completely, whether conscious or unconscious. Editor: It’s so easy to forget photography's connection to preservation and loss. As you mention the industrial revolution, I start seeing Talbot’s work less as an attempt at documenting nature perfectly and more of an active attempt at conservation of an ideal of nature. Curator: The photograph acts as both a scientific document and an elegy. It's interesting how new technologies intersect with societal fears and desires. Talbot gives permanence, or at least an illusion of it, to the fleeting beauty of nature. Editor: Precisely. In a world rapidly changing, Talbot uses a cutting-edge technique to create enduring visual icons, linking the symbolic power of flora with the emerging age of mechanical reproduction. This "Botanical Specimen" becomes more than just a picture. Curator: Indeed, I see in this specimen of Talbot’s a visual dialogue of the real, with the ideal, capturing, even as we view it today, its long-faded original beauty. Editor: Looking closer I can feel how technology forever changed the language of symbolism. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.