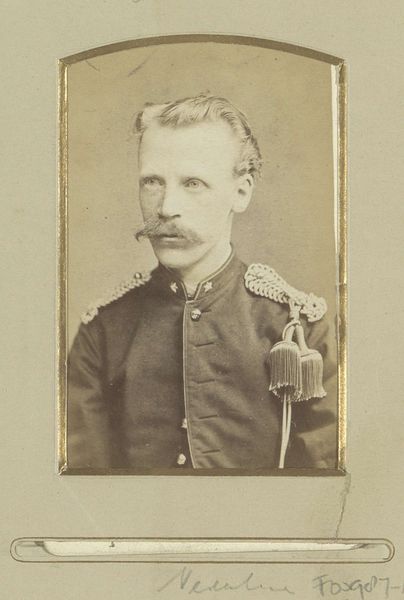

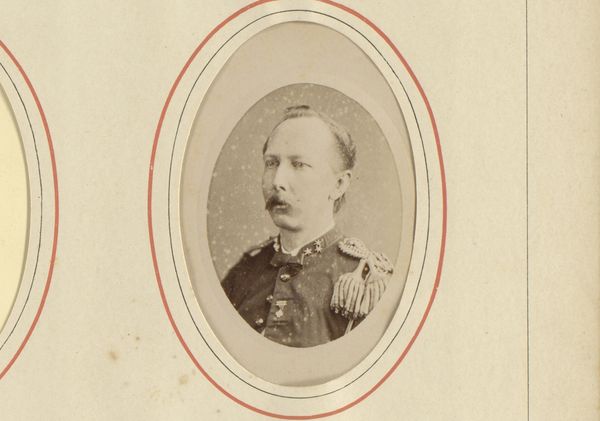

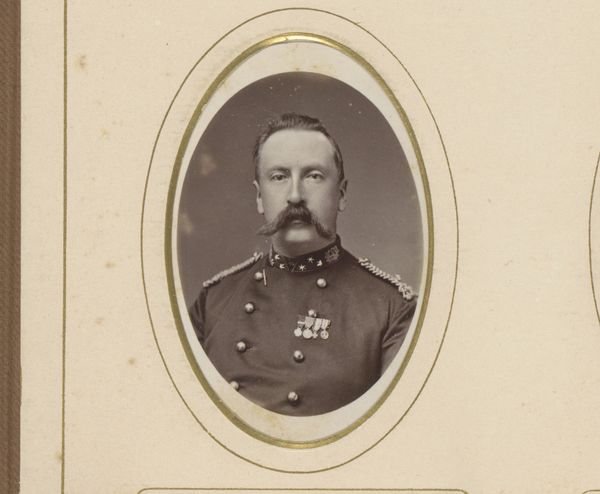

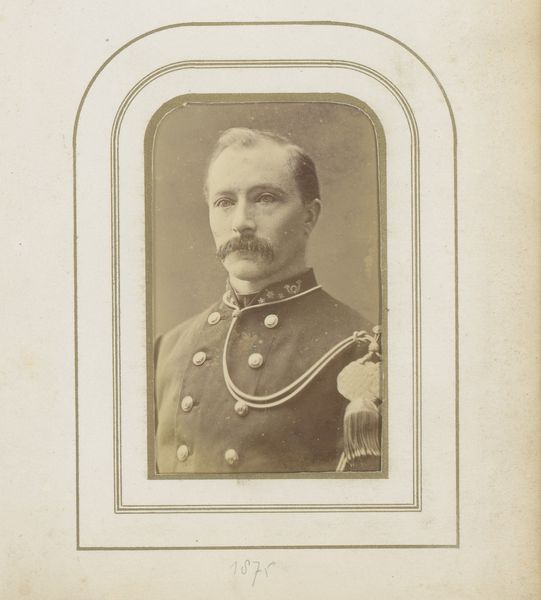

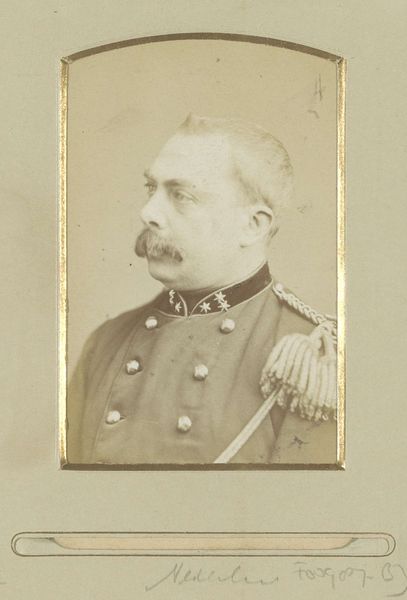

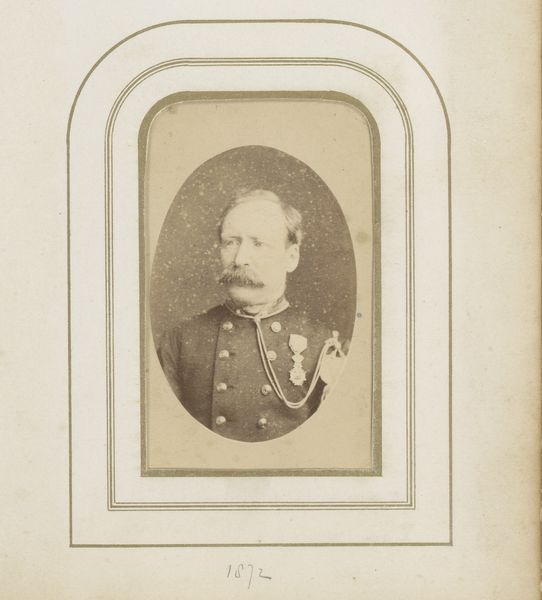

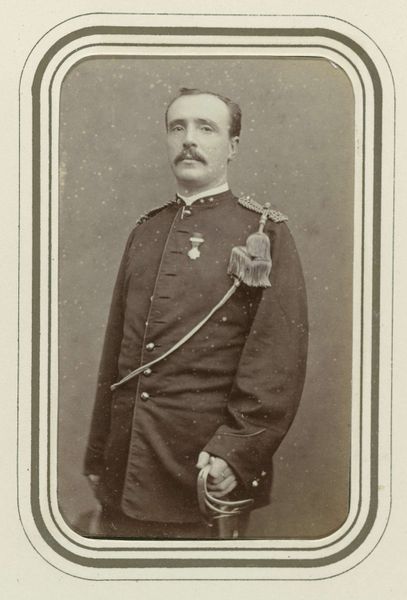

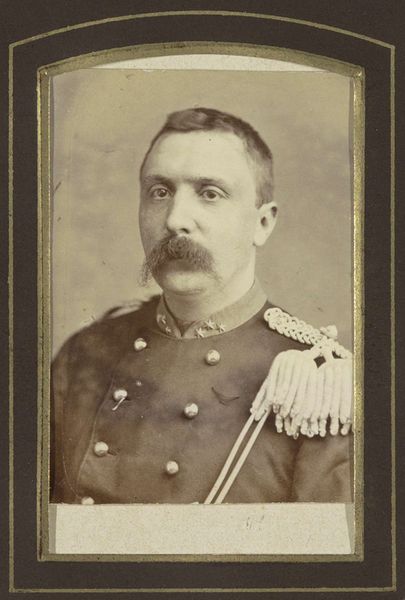

Portret van een (vermoedelijk) Nederlandse militair c. 1868 - 1896

0:00

0:00

louisrobertwerner

Rijksmuseum

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

19th century

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 102 mm, width 64 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This albumen print, dating roughly from 1868 to 1896, presents a rather stern-looking gentleman. It's held here at the Rijksmuseum, listed as "Portret van een (vermoedelijk) Nederlandse militair" - "Portrait of a (presumably) Dutch military man," created by Louis Robert Werner. It has such an austere yet intimate quality. Editor: He does look formidable! It’s the sharpness of his mustache, perhaps, juxtaposed with the soft sepia tones that lend it that historical gravitas. What do you make of the frame, the oval within the rectangular mount? It adds an element of deliberate staging, doesn't it? Curator: Absolutely, there’s a consciousness of presentation at play. Think about it: albumen prints were a way to democratize portraiture, moving it away from the realm of only the wealthy. But the uniform, the medals… It also signifies a certain elite status, a life committed to service, duty. The slight blur in focus feels almost like a memory fading at the edges. Editor: Indeed, and in what context are we viewing it? It's not just a portrait of military merit. The portrait comes from the Netherlands at a time when it sought to violently exert control over its colonial holdings, particularly in Southeast Asia. Can we think of this figure without considering his potential involvement in those colonial structures and atrocities? Curator: It is true that by the time this picture was taken, these men are implicated in some of the darkest chapters of Dutch colonial history. Does the gaze reflect complicity? What secrets do those eyes hold? Editor: Right. The power of these images lies not just in the surface representation but also in the silences and the unacknowledged histories they carry. The photograph might offer a surface sheen of national pride, but, beneath, we must acknowledge the narratives of subjugation and oppression they silently perpetuate. Curator: So how can we use these artefacts—this photographic evidence of history — to reckon with both the grand narratives and the inconvenient truths? Perhaps it is precisely in those moments of discomfort that art invites critical self-reflection and promotes a reevaluation of who we are. Editor: I think that this picture and its ambivalent place in history should offer us that chance, exactly.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.