drawing, ink, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

pencil

Copyright: Public Domain

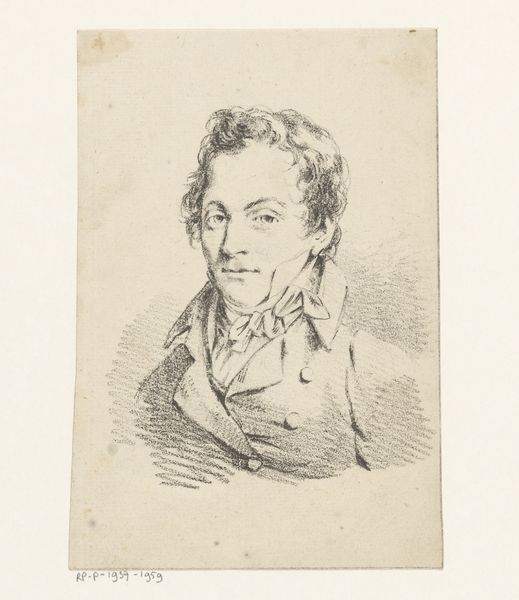

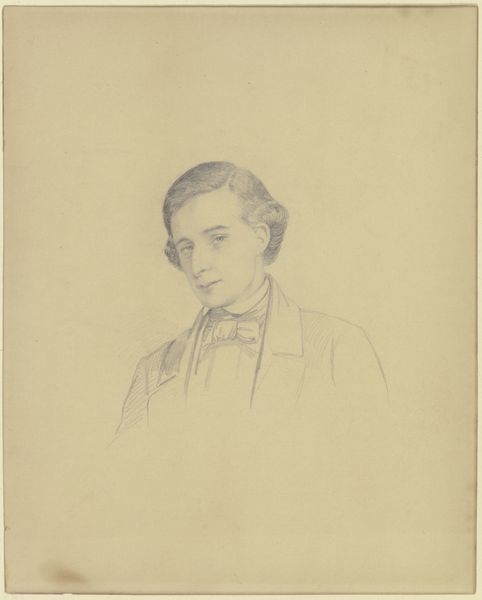

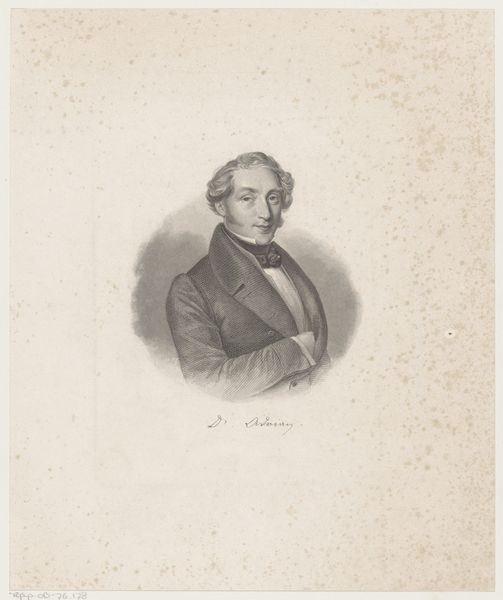

Curator: Welcome! We’re standing before Wilhelm von Kobell’s “Brustbildnis des Malers Hummel,” a drawing rendered in pencil and ink currently residing here at the Städel Museum. Editor: My first impression is one of thoughtful reserve. There's a gentle melancholy in the subject's gaze, a sense of quiet contemplation that speaks volumes even without grand gestures or dramatic coloring. Curator: It's interesting you say that. I wonder, how much of our perception of melancholy in this image comes from our retrospective knowledge of Romantic ideals permeating art at the time? This piece emerges from a socio-cultural environment that valorized sentimentality and subjective experiences. Editor: Precisely! The posture, leaning slightly back as if burdened by thought, and that almost pained expression… I also feel a deliberate construction of the male artist as intellectual and sensitive. It’s a clear move away from previous eras that primarily equated artistic merit with technical skill. Curator: Yes, but even within the trope, I find the presentation fascinating. Note the precision of the line work defining his jacket juxtaposed against the more fluid, almost wispy rendering of his hair. It's as if Kobell seeks to capture not just Hummel’s likeness but also his very essence. Editor: The clothing, while finely detailed, also signifies something about class and identity, doesn’t it? We're seeing the rise of a bourgeois class that is now commissioning art, and portraits like this solidify their social standing through artistic representation. Curator: And Hummel, the artist himself, being depicted—there's a self-awareness to it all. Artists were, in a way, creating their own narratives, choosing how they would be remembered and perceived by society. It’s fascinating how these drawings function almost as PR for the artistic community. Editor: It really shows that portraiture became a space where one could negotiate identity, class, and status but also create and promote specific ideologies that persist through institutions like museums, thus creating even further conversations. Curator: Absolutely. I always appreciate how even the simplest works on paper can reveal such profound historical and social complexities. Editor: Agreed. It is truly exciting how, in such subtle brushstrokes and in these light pencil lines, such social meanings are drawn out for us today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.