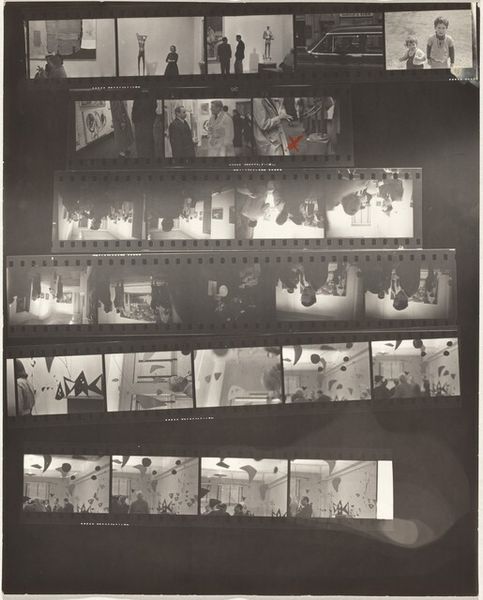

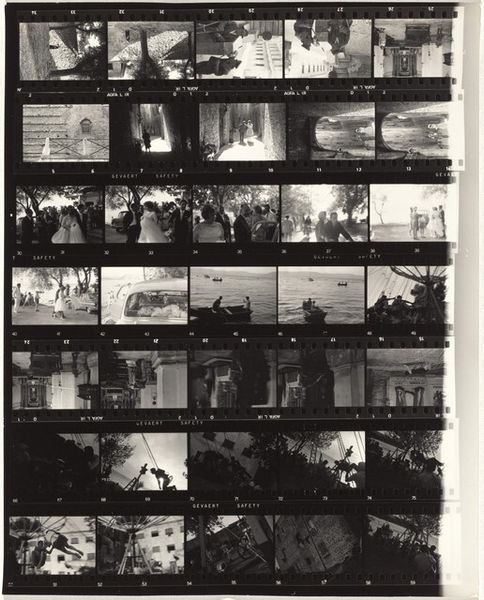

Dimensions: sheet: 20.2 x 25.2 cm (7 15/16 x 9 15/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

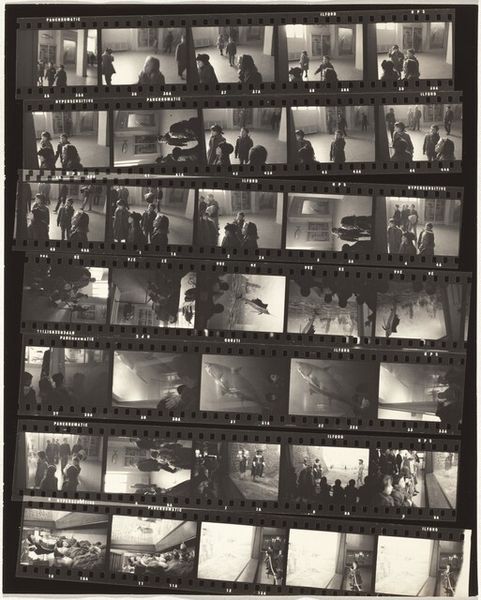

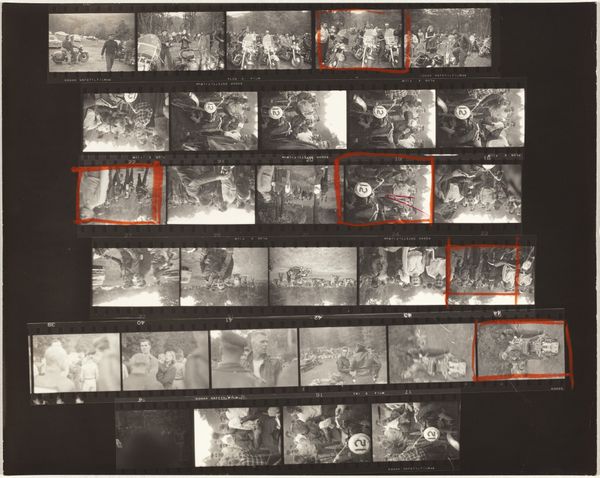

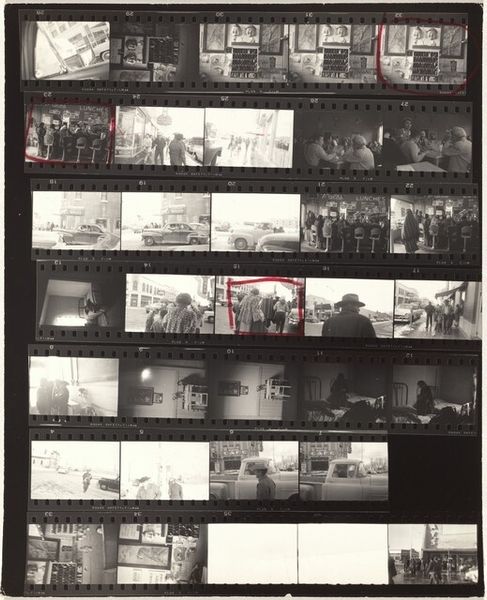

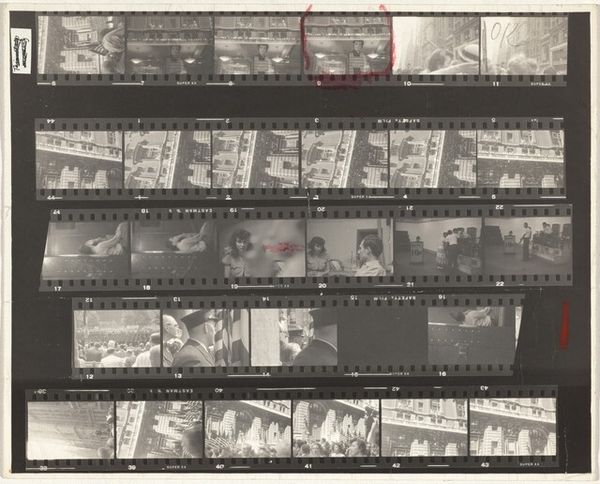

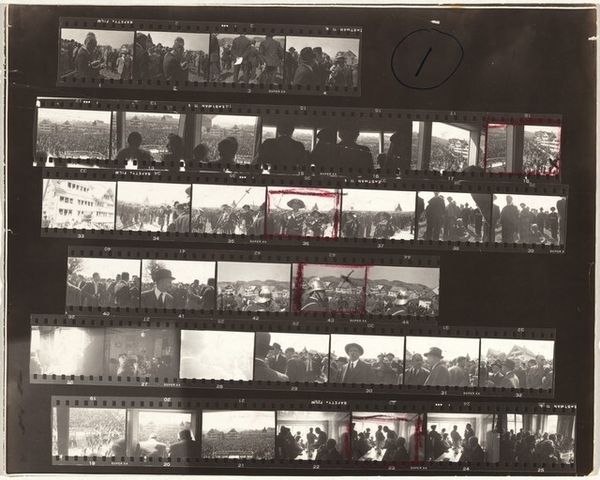

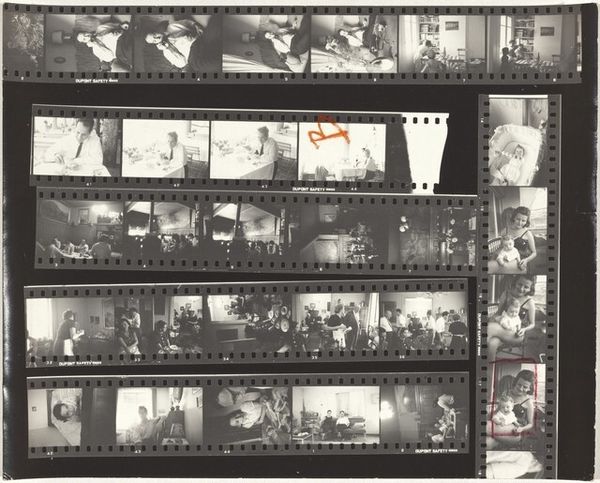

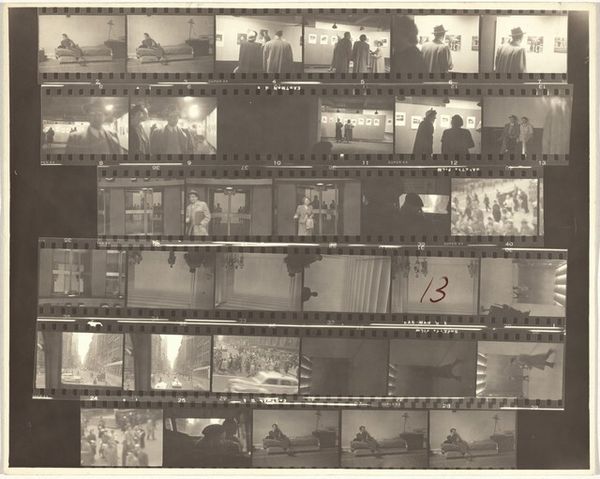

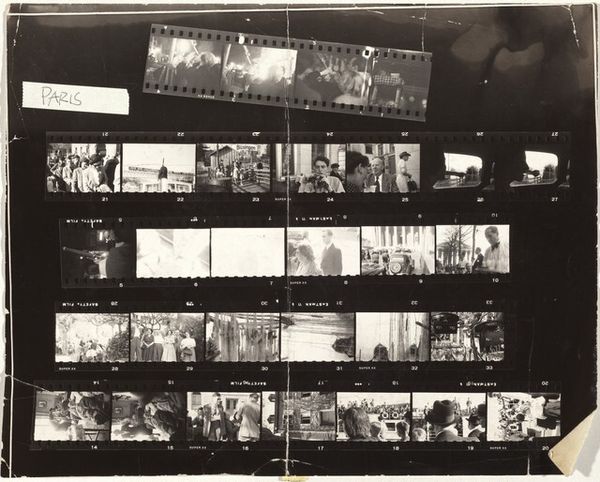

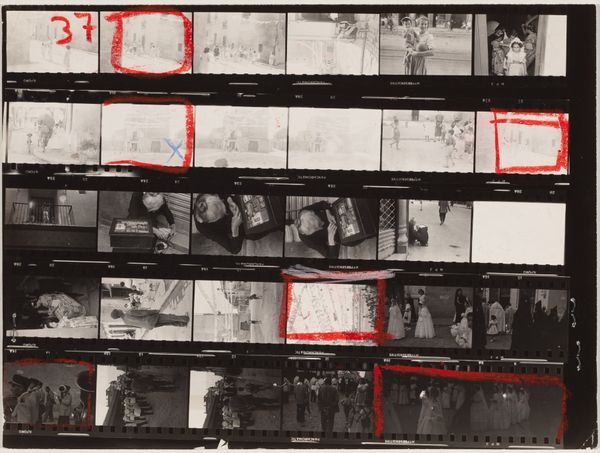

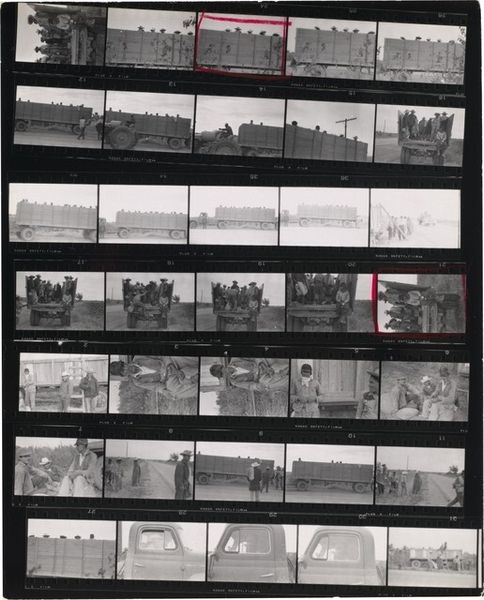

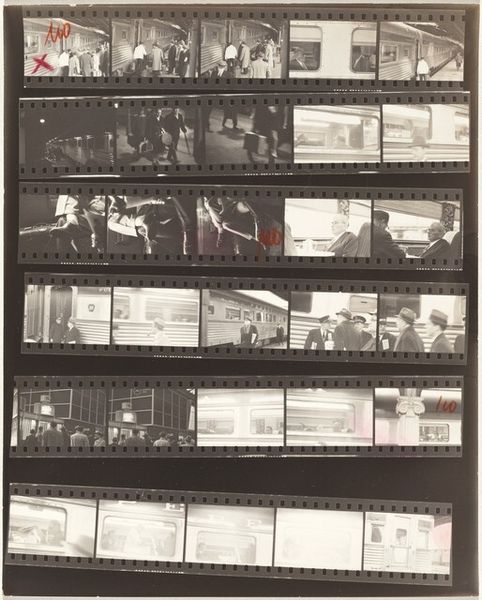

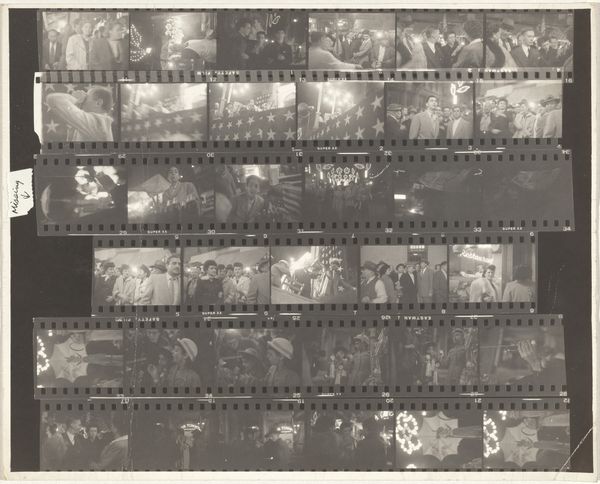

Curator: Let’s spend some time looking at Robert Frank’s piece, “Family and Edouard Boubat—New York City no number,” a gelatin silver print from 1953. What are your first impressions? Editor: Fragmented, almost like a contact sheet from a film roll. The tonal range is limited but compelling, drawing you into each individual frame even as you’re aware of their arrangement as a whole. Curator: Frank was Swiss-American, and part of the New York School of photographers. He’s really known for his raw, seemingly spontaneous style which, at the time, was a stark departure from the carefully staged photography so popular in the 40s and 50s. This particular work gives us an interesting behind-the-scenes peek. Editor: The sequencing definitely provides a narrative. You see moments both public—crowds on a busy street—and private, with individuals at a cafe or examining pictures hung on the wall. The contrasts feel intentional, right? Curator: Absolutely. This work emerged during a fascinating period. There was growing disillusionment with the post-war American dream, simmering beneath the surface of the supposed consensus culture. Frank captured that unease. It’s also worth noting he originally intended this as a preliminary layout for a book, before it evolved into an artwork on its own. Editor: The composition highlights that tension perfectly. The gritty, unglamorous aesthetic undermines any sense of idyllic domesticity. The tight cropping almost feels voyeuristic in sections. Curator: Frank certainly challenged prevailing norms, both artistically and socially. His lens captured ordinary Americans, often overlooked, and it did so in a way that resonated deeply with the burgeoning counterculture. He was criticized, of course, for portraying a negative image of America, but that’s exactly what made his work so revolutionary. Editor: It’s funny, though, seeing this now. You see a rejection of aesthetic traditions on one level, but also the employment of pictorial structure at another, like an anti-aesthetic gesture performed using purely aesthetic means. Curator: Well, I’d argue that Frank's 'negative image' wasn't just about exposing problems, but humanizing everyday struggles. He provided a visual vocabulary for understanding the complexities of American life at the time. Editor: A fascinating visual document and, ultimately, an example of brilliant composition within limitation. Curator: A potent reminder of the power of art to reflect, critique, and shape our understanding of society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.