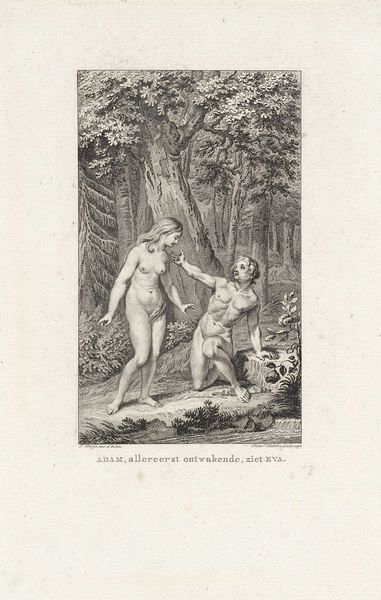

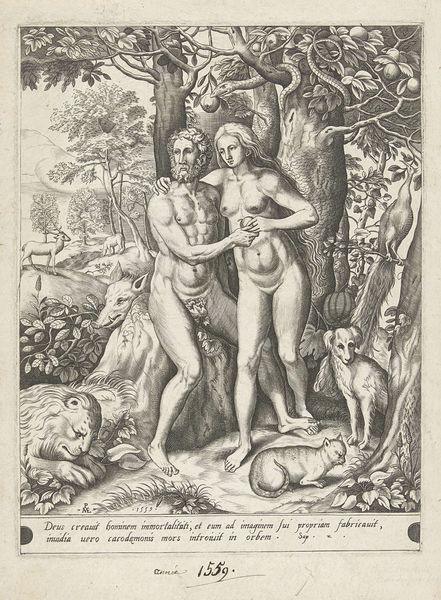

Dimensions: height 115 mm, width 85 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

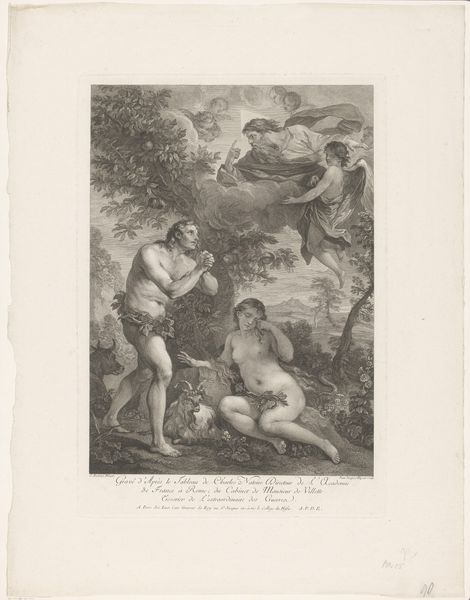

Curator: This is Jacob Ernst Marcus's 1819 engraving, "The Temptation of Adam and Eve in Paradise," currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum. My first thought goes to the sheer weight of history. Editor: It strikes me as a strangely subdued depiction, especially given the magnitude of the subject matter. Everything is so meticulously rendered; it feels almost academic. Curator: Exactly! Think of the socio-political climate back then. Public art had a very specific role, often didactic, reinforcing accepted narratives. So, instead of dramatic license, we get what reads to me as this considered realism. It aims for clarity in the service of its allegorical message. Editor: That message, though—the serpent coiled in the tree, its gaze so knowing. Snakes, of course, are so often associated with feminine wisdom, and here, we see Eve in the dominant position, tempting Adam. This reverses our expected understanding that links Eve's name to the source of life. Does this artist dare to question the church's authority? Curator: What about the lion consuming the lamb down there at the bottom? Editor: I see them also! How can the lion feed from an animal if death and flesh only appear in life as the consequence of the original sin? Curator: Maybe the death and the sin already were living into the world, a consequence of Eve reaching toward that fruit, ignoring Adam's questioning. That fruit isn't so innocent itself! Eating fruit is commonly seen as the symbol of indulgence. But notice, the lines of the serpent's scales lead your eye right into the curves of the fruit. Symbolically speaking, this reinforces the fruit's place as the connector between nature and knowledge, the bridge between divinity and earthly existence. Editor: Very astute observations, friend. Curator: Well, thank you. But if we're thinking about the role of this piece in 1819, we should remember engravings like these were easily reproducible. This print was accessible, disseminable. It entered into a dialogue. And still does. Editor: Indeed. Seeing this engraving offers a fascinating lens through which to consider both individual choice and society's narrative control. Curator: Precisely. It's a reminder of the power—and the politics—inherent in images.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.