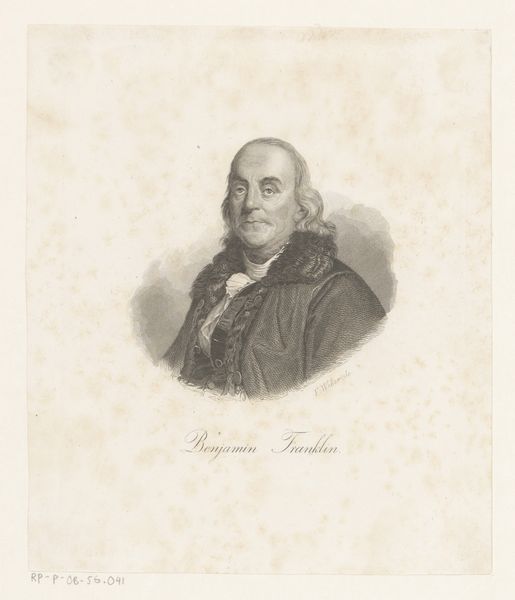

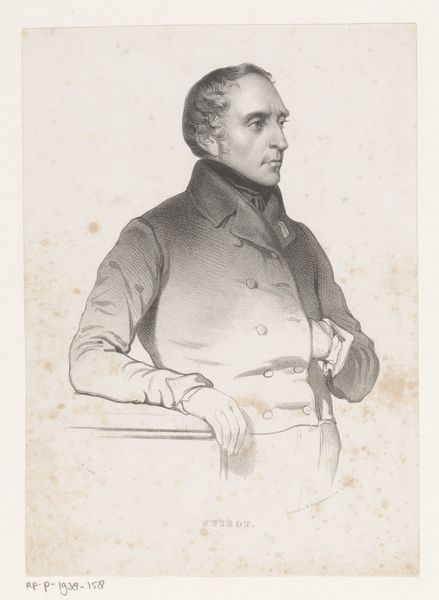

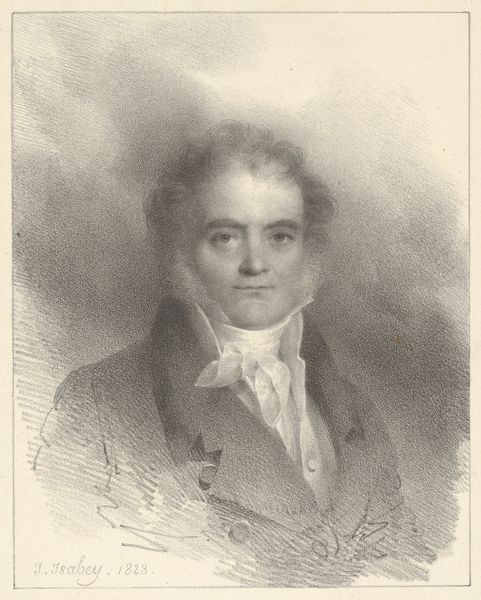

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

engraving

Dimensions: 218 × 294 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have an engraving from November 1814, titled "Sir William Beechey, R.A." at the Art Institute of Chicago, a portrait after an original picture by himself, with W. Evans as the draughtsman and R. Cooper the engraver. What’s your initial reaction? Editor: There's a reserved but determined energy, I would say. It's remarkable how much texture the engraver captured on his coat using what looks like layered techniques. You can sense its weight and formality. Curator: Absolutely. This work and era are right at the nexus of social power and artistic production. Romanticism in Britain offered avenues for artists like Beechey to self-fashion not just aesthetically but socially. Editor: Right, he literally re-presents himself. Thinking about the materiality of portraiture at this time, it's such a direct engagement with elite networks and the economics of representation. Commissioned portraits, like paintings but also engravings, affirmed the social status and material success of the sitter but also of the artist, the engraver, and the printer. Curator: The layers are so telling. This print comes after Beechey’s own self-portrait and it places him in conversation with the Royal Academy – the "R.A." in the title being crucial to understand his position. His engagement with the Romantic style isn’t purely aesthetic. He's positioning himself within debates around national identity, idealised beauty, and the artist as a kind of genius. Editor: And that "genius" is partly crafted through access. Access to materials, access to patronage. Look at the fineness of the engraving on his face, compared with the relatively sparse hatching on the background, creating this spotlight effect—it guides the eye to read his persona and artistic prestige. It says something that the printmaking labor of W. Evans and R. Cooper are given some acknowledgement but are nevertheless secondary. Curator: Yes. The way it reflects both his identity as an artist within the cultural landscape, and how those representations themselves reinforce societal power structures—both artist and sitter were caught in this game. Editor: In the end, though, there's something enduring about witnessing this carefully constructed image over time. It invites us to question how identities and histories are produced through visual means and what power dynamics inform such processes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.