painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

group-portraits

#

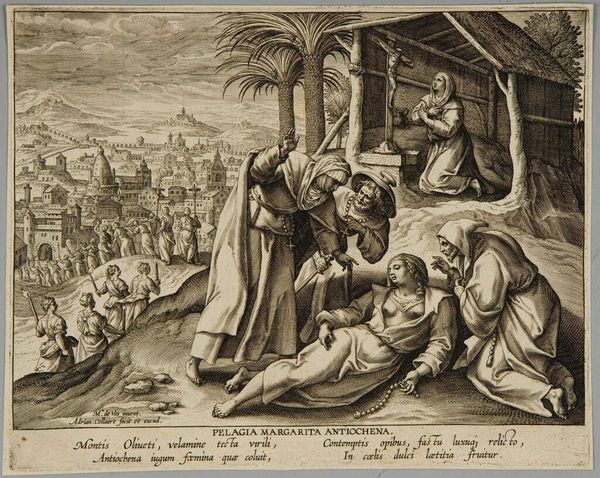

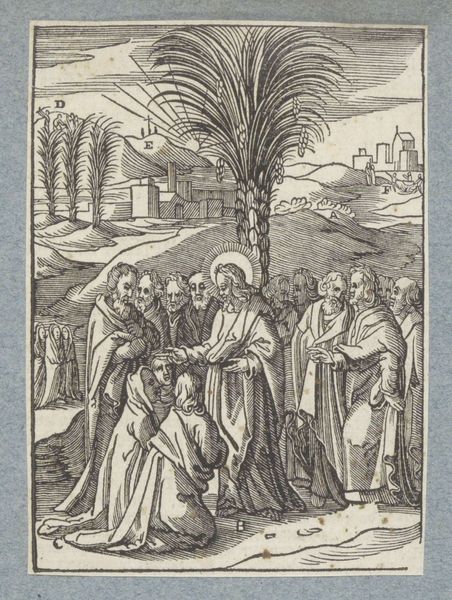

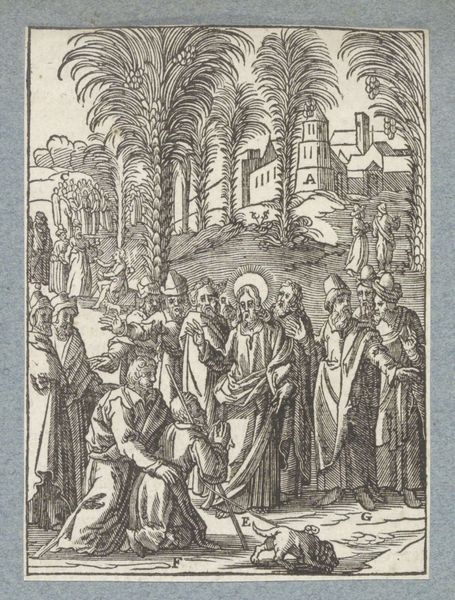

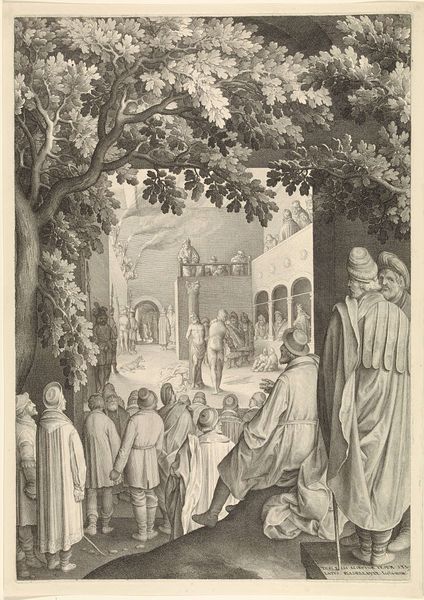

christianity

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

early-renaissance

Dimensions: 211 x 141 cm

Copyright: Public domain

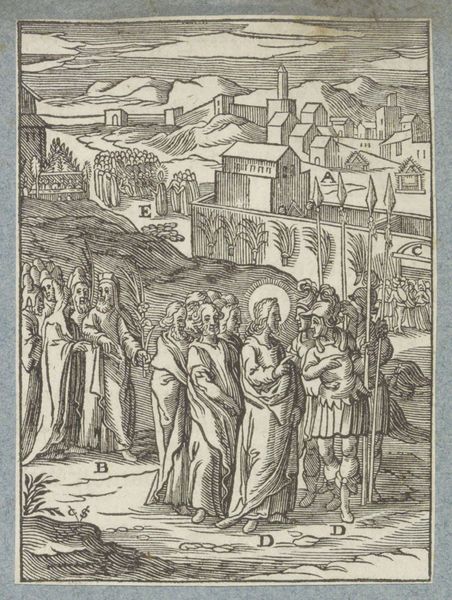

Curator: Let's talk about Vittore Carpaccio's "Burial of St. Jerome," painted in 1509 with oil paint. What strikes you about this piece? Editor: It’s interesting to see the burial happening in what looks like a very public space. Everyone seems busy; even animals are wandering about. It doesn't feel somber, exactly. How do you read this work? Curator: I'm fascinated by the juxtaposition of the sacred and the mundane here, and how Carpaccio uses materials to signal it. Note how the divine is rendered with just as much, or even less, refinement of details as that of the day-to-day. The pigment itself is just oil and ground minerals, laboriously mixed. No element is given any more worth than another – the scene of St. Jerome’s burial is visually of a kind with that of the buildings, animals, and vegetation beyond the steps, implying the death of this one man may not be so special. How might the patrons receiving this art in their community receive that commentary, knowing their commission dollars purchased just this representation? Editor: That's a really interesting point! I hadn’t considered the equal distribution of labor and value implied in the material treatment of the scene. It feels almost subversive for a religious painting. Were his patrons aware that he was leveling everything in such a manner? Curator: That's the core of the tension, isn't it? They wanted to publicly show and venerate, but the art is materially rendered in such a way that renders it almost profane. It forces a reassessment of artistic creation, material, and how these converge to reflect larger power dynamics. Editor: So, by examining the artistic materials and production processes, we uncover this implicit commentary about the art itself and possibly Italian Renaissance society's relationship with the Church? Curator: Precisely! The very act of painting becomes a form of social critique, questioning value systems. I have to rethink my relationship with art. Editor: Definitely! I’ll certainly look at other Renaissance pieces in a different light, considering the socio-economic implications imbued in even the simple art supplies and painting methods of the time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.