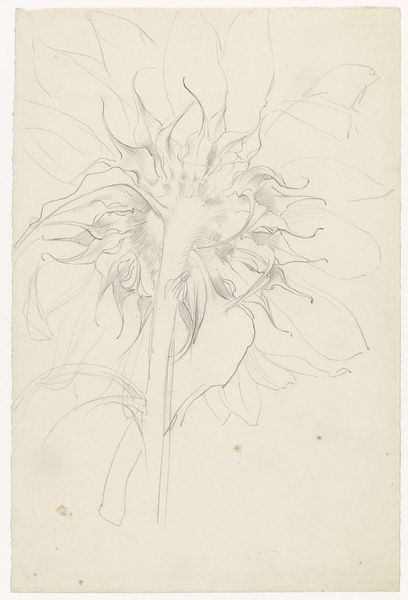

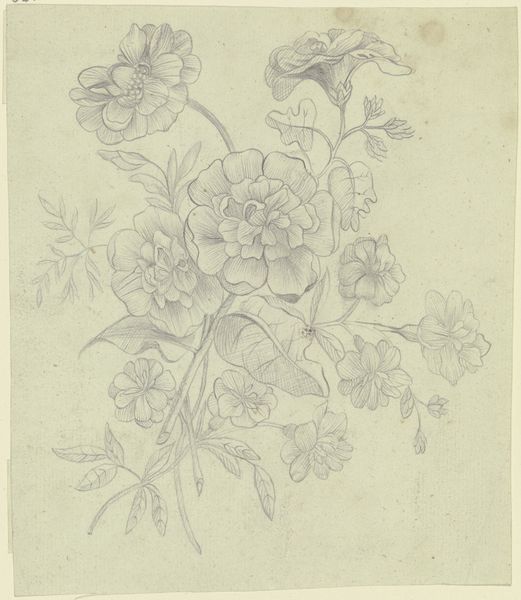

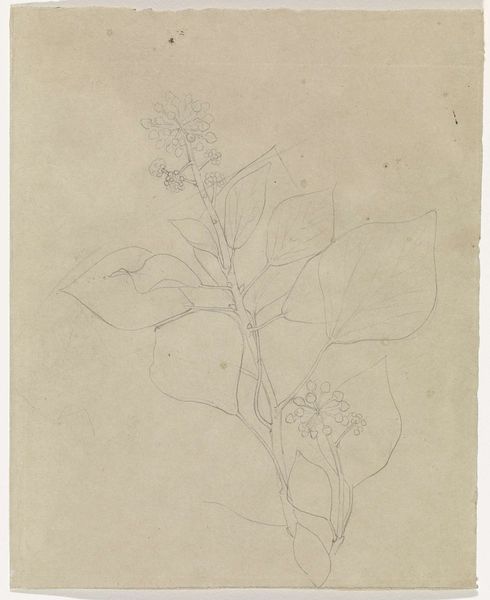

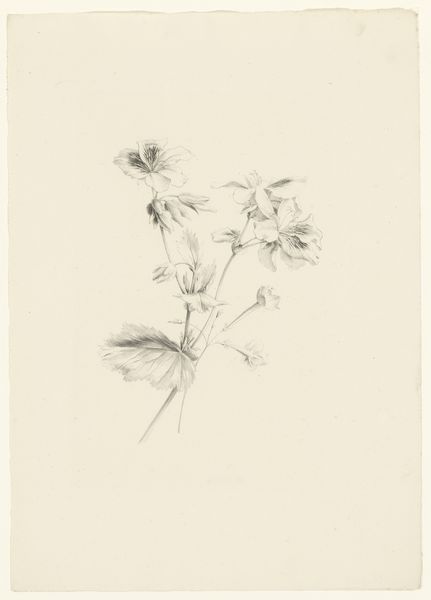

drawing, pencil

#

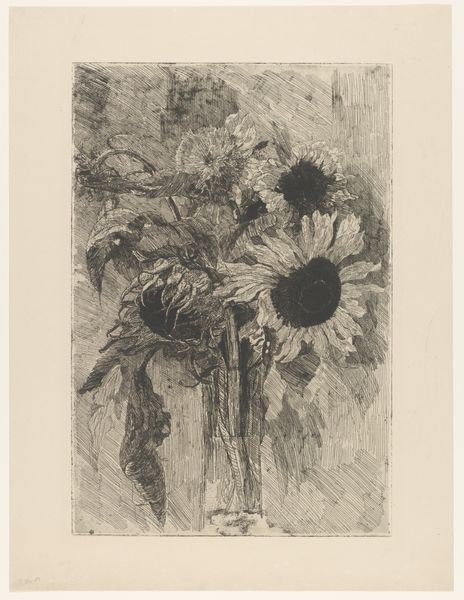

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

watercolour illustration

Dimensions: height 490 mm, width 397 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

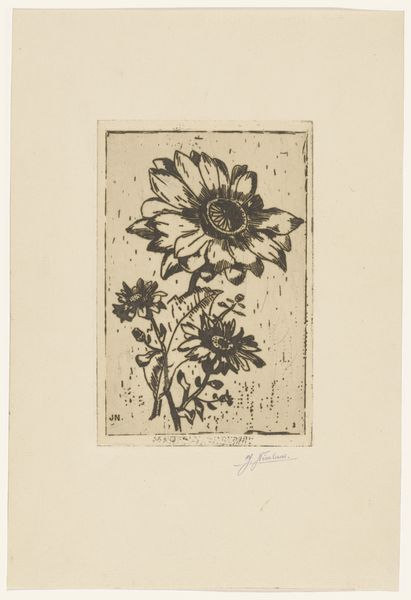

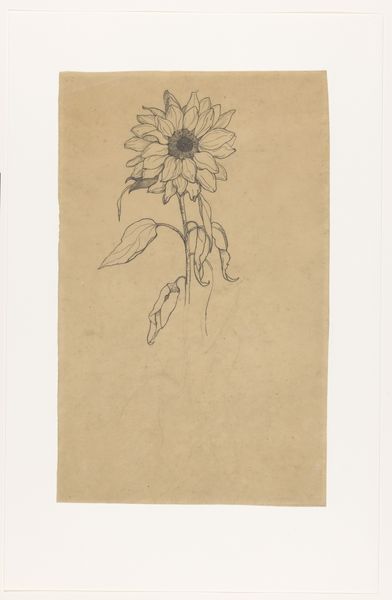

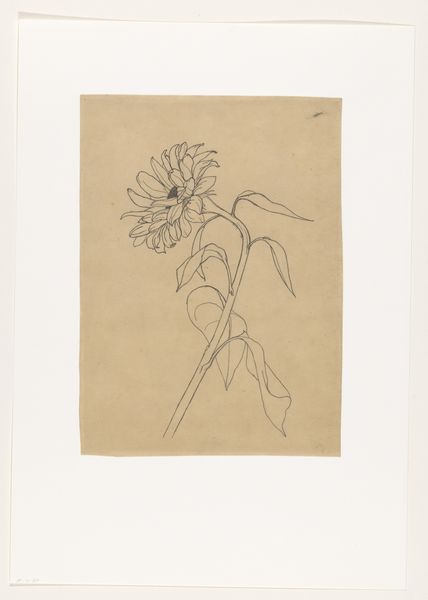

Editor: Richard Nicolaüs Roland Holst’s "Sunflowers," created in 1892, presents a captivating pencil drawing, seemingly simple, yet possessing a haunting quality. The sunflower heads droop, conveying a sense of melancholy and the transient nature of beauty. What do you see in this piece? Curator: It's crucial to acknowledge how these "Sunflowers," though seemingly a benign still life, might reflect the sociopolitical atmosphere of the late 19th century. Consider the symbolism embedded within the motif of wilting flowers. Is Holst commenting, perhaps unconsciously, on the fading societal structures or the decline of certain power dynamics of his time? The very act of choosing sunflowers, plants that boldly face the sun, only to depict them in decline, introduces a tension ripe for interpretation. Editor: That's interesting. I hadn’t thought of the wilting as anything more than a botanical stage of life, rather than a reflection of society at large. Curator: Precisely. It's about challenging the assumption that art exists in a vacuum. What does it mean to create an image of nature failing to thrive during a period of industrial growth and perhaps also considering shifts in cultural hegemonies in Dutch society? The medium, pencil, lends itself to a certain quiet intimacy, further complicating the narrative. Editor: So, are you saying Holst's choice to depict wilting sunflowers connects with the industrial changes happening? How can a drawing do that? Curator: It isn't a direct depiction, of course. But think of the Romantic movement's rejection of industrialization. This piece, made a little later, seems to echo those sentiments by pointing to a potential decay through something like dying sunflowers. Consider the work as participating in an ongoing discourse about the costs of progress and our relationship to the natural world. The fragility rendered in pencil becomes a statement in itself. Editor: I see. Thank you. It really encourages me to look at art through a wider lens, beyond just aesthetics. Curator: Absolutely. And questioning the artist's intention, even if speculative, allows for a more nuanced engagement with the work, broadening our understanding of its place in history.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

Roland Holst was one of Vincent van Gogh’s first admirers. He helped organise a Van Gogh exhibition in Amsterdam in the winter of 1892-1893. For the accompanying catalogue he designed a cover illustrating a dying sunflower before the setting sun. Perhaps somewhat less sentimental is this detailed, forcefully drawn study of an overblown sunflower.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.