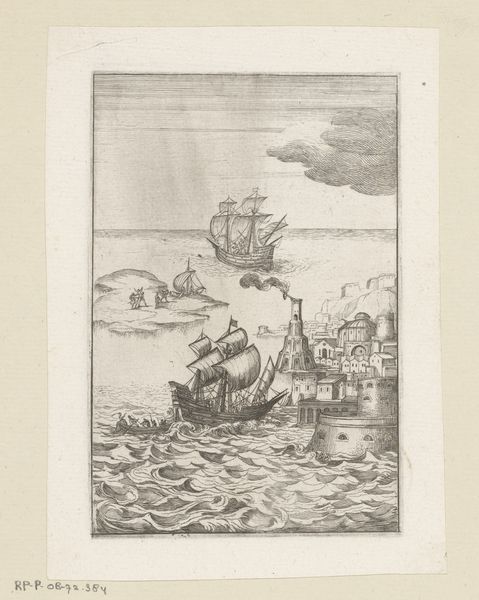

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 235 mm, width 176 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

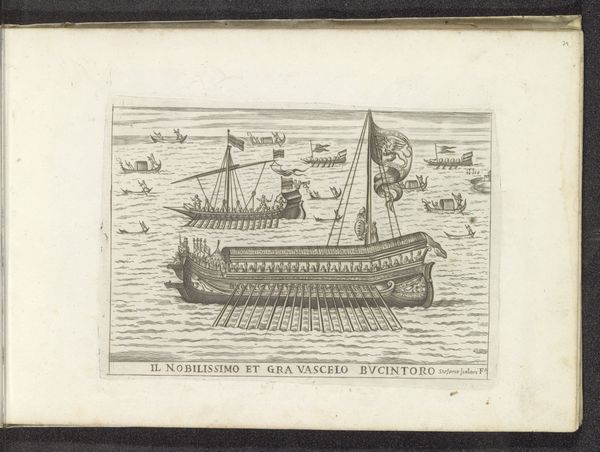

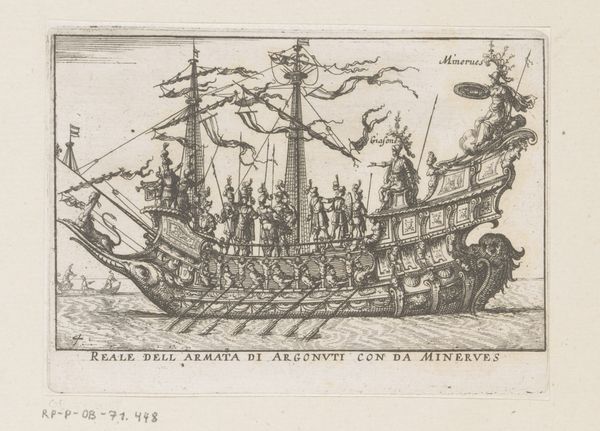

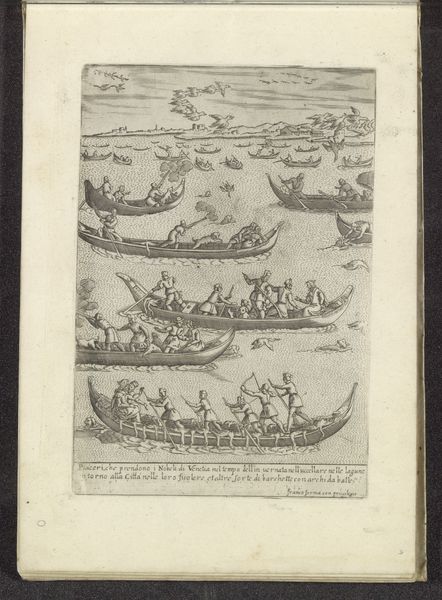

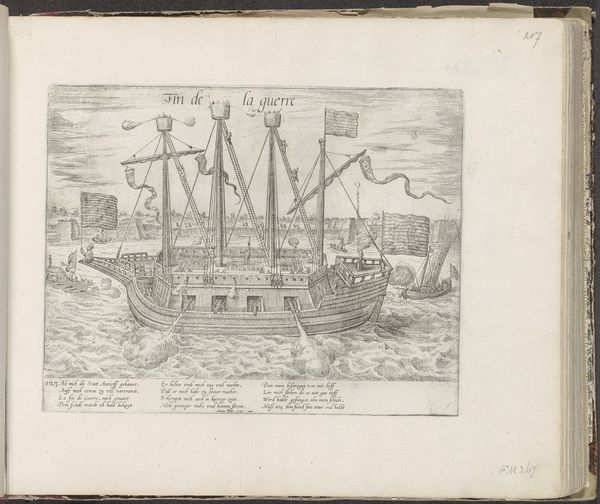

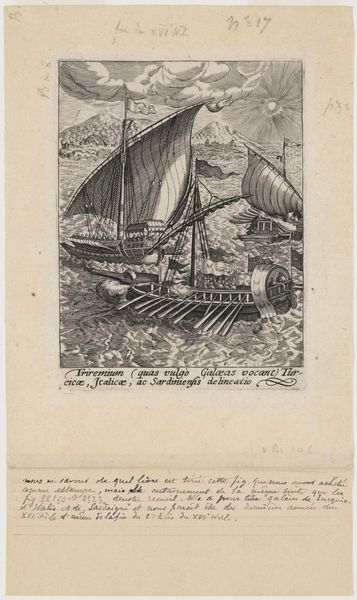

Curator: This is an engraving titled "Festa della Sensa," created around 1610. The Rijksmuseum currently holds it. What stands out to you initially? Editor: It's a bustling scene, almost claustrophobic. Despite the open water, the sheer number of vessels, particularly those galleys, creates a sense of tension, of potential conflict simmering beneath the surface of celebration. Curator: The "Festa della Sensa," or the Ascension Day Festival, was a major Venetian holiday. This print probably depicts a symbolic marriage of Venice to the sea, solidifying its maritime power. Editor: "Marriage" implies union and consent, but knowing Venice's history, especially its imperial reach and exploitation of other cultures through sea power, "domination" feels like a more apt description of this relationship. The galleys are clearly symbols of military strength. The festival was designed to promote that sense of authority. Curator: The imagery certainly leans into that projection of power. Galleys, with their oars, represent the forceful exertion of Venetian will, while their scale and ornamentation signal the state's wealth and refinement. Venice loved pageantry. It all became iconography quickly. Editor: Yes, and the image underscores who truly holds that power: the white figures on the large ships versus the much smaller dark figures populating all the boats. Is this just about wealth and display, or are there deeply coded signifiers related to race and power being embedded in a relatively innocuous festive scene? It definitely prompts me to see how such spectacles worked to naturalize inequality. Curator: Consider that it wasn't only about subjugation. Festivals were, and continue to be, moments where cultural narratives are reinforced, memories cemented. It speaks volumes about how Venice wished to be seen, both internally and to the world, its story propagated through ritual and symbol. Editor: I suppose. Ultimately, the picture serves as a reminder that celebrations aren't innocent. We always need to critically examine whose interests they are designed to serve, which is so vital for any form of visual analysis, centuries ago, or now. Curator: Exactly. Thinking about what persists and transforms in cultural memory from that time can reveal a lot.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.