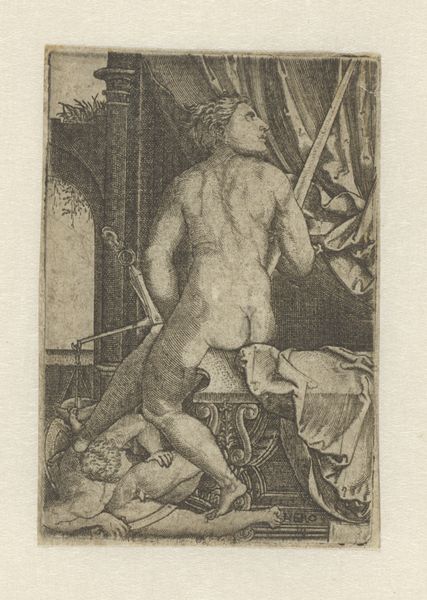

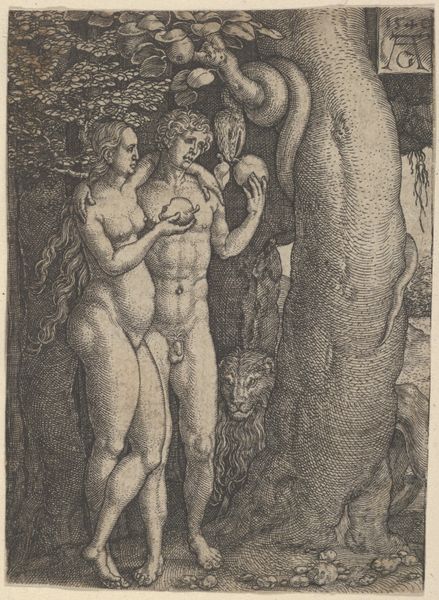

Dimensions: Sheet: 3 13/16 × 2 9/16 in. (9.7 × 6.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

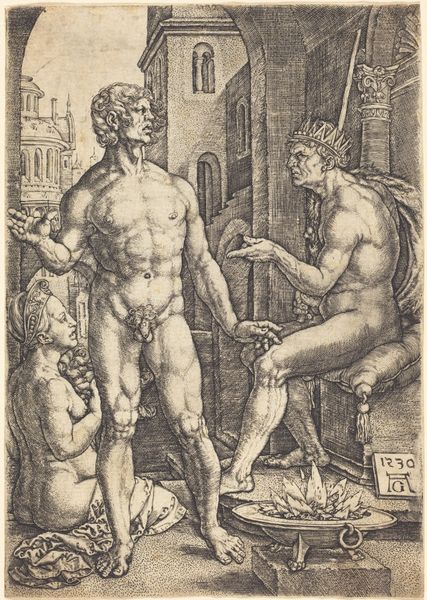

Curator: Here we have Heinrich Aldegrever’s “Jupiter, from ‘The Seven Planets,’” an intaglio print dating back to 1533. It's currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: Immediately striking, isn't it? Stark. Feels like an illustration from some half-remembered myth. Like the old gods caught between worlds, powerful, yet somehow vulnerable rendered in those sharp, unforgiving lines. Curator: Aldegrever, a key figure in German printmaking, employed engraving techniques here. Consider the materials involved – the copperplate, the burin, the ink. This wasn’t just about artistic expression, but about the labor-intensive process of producing multiples for wider distribution. Editor: Right, you can almost feel the artist's hand, can't you? Pressing into the metal, those deliberate scratches making light appear. He makes a sort of hauntingly human, fleshy god—quite unlike those idealized Renaissance depictions. The whole composition gives me chills—especially with the small archer. Curator: The "Jupiter" print served a very specific social function at the time, reinforcing certain astrological and philosophical beliefs for consumption among educated elites. Editor: Jupiter looks burdened to me. Heavy-crowned, like the weight of divine responsibility actually hurts. Even his muscularity appears weary; the engraver almost etched in age on that brow. Curator: We should also point out the cupid on the left—is this a gesture symbolizing a deeper layer? Editor: A nice addition to what could have been a simple composition: Aldegrever's added the cupid aiming a crossbow at Jupiter. Curator: Considering Aldegrever's social context, what about possible influences of Lutheranism in the depiction—questioning religious institutions? Editor: Or he may have thought it added character to the piece; gave it more soul, no? It's strangely compelling, and the way he depicts flesh and weight… There’s this almost… brutish beauty, stark and arresting. What more can we say than bravo, or hoch soll er leben? Curator: Indeed, and it exemplifies how prints functioned both as artistic expressions and products embedded within a complex socio-economic system. Editor: Agreed. This glimpse has altered how I engage with the past—not just seeing, but *feeling* the grit of history under one's fingers.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.