photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

black and white photography

#

portrait image

#

black and white format

#

street-photography

#

photography

#

black and white

#

single portrait

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

monochrome

Dimensions: sheet: 35.3 × 27.8 cm (13 7/8 × 10 15/16 in.) image: 32.2 × 24.8 cm (12 11/16 × 9 3/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

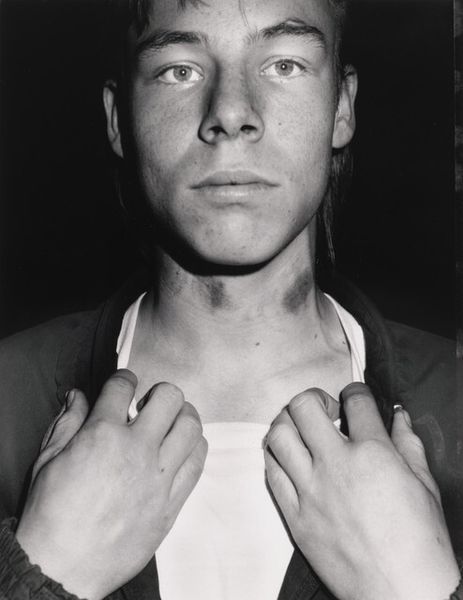

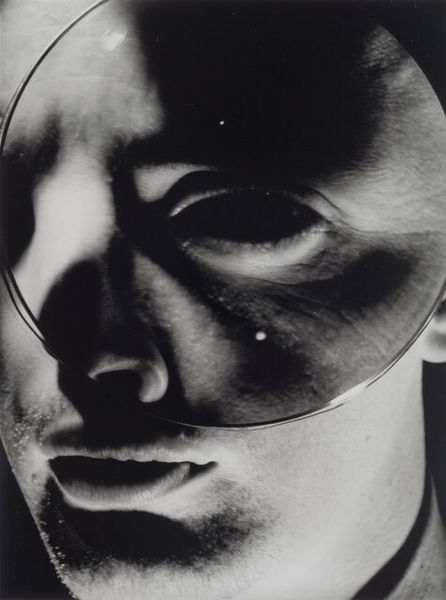

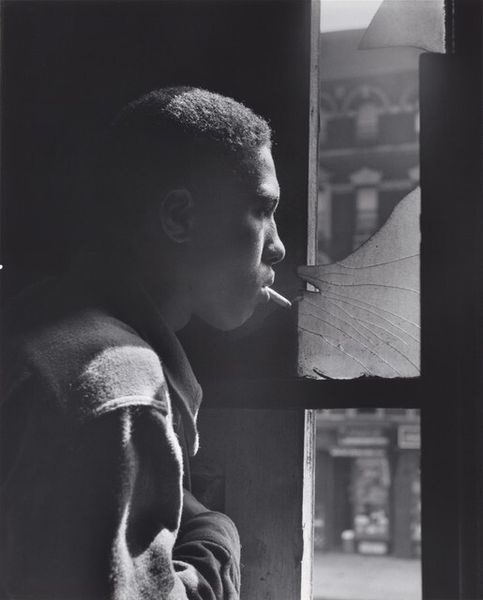

Curator: This black and white photograph, possibly created between 1991 and 1994, is titled “Zhodi” and was made by Jim Goldberg, using a gelatin silver print. It's a stark, intimate portrait. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: My first reaction is unease. There's something deeply unsettling about the exposure and vulnerability captured here, and the manipulation around the eye certainly amplifies that feeling. Curator: Right, and the photograph is a gelatin silver print, a process perfected in the late 19th century that remained the standard for black-and-white photography for many years. Think about the labor, the darkroom processes, the meticulous control involved. Editor: That meticulousness creates tension with the subject's evident vulnerability. I can't help but consider what the use of this medium suggests in terms of control, considering the socio-political conditions. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the work involved in developing and printing. Gelatin silver printing necessitates particular knowledge, which often involves mastering specialized labor practices; Goldberg clearly had access to these techniques, and access can shape both content and distribution. Editor: This image speaks volumes about identity and representation. A street photography portrait requires the consent to construct, document, and perhaps even exploit individual identities in public, so one could see its subjects from an activist lens. Who has the authority to visually fix others? Curator: A central element in all of this involves not just what is visible in the image, but also who can perform these processes and their inherent cost. Understanding that is crucial, because labor determines the ultimate content in a deep way. Editor: Indeed. “Zhodi” becomes a potent reminder that visual media is never neutral; it's laden with the complex baggage of how identities are mediated by the tools and economic dynamics present during its production and viewing. I keep considering how power functions within photography as both medium and practice, here. Curator: By drawing out how such social contexts intertwine in every phase of “Zhodi”, we might now reconsider the relationships between the subject in the photograph, its medium, and its impact on visual culture. Editor: Absolutely; that's the first step towards understanding the multilayered implications for individuals both in the image, and outside of it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.