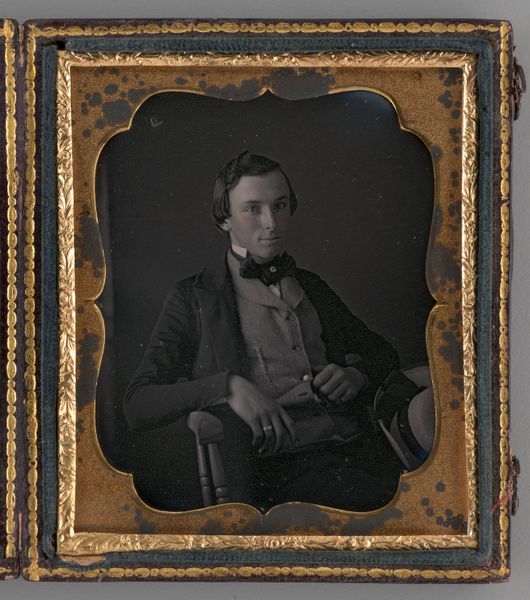

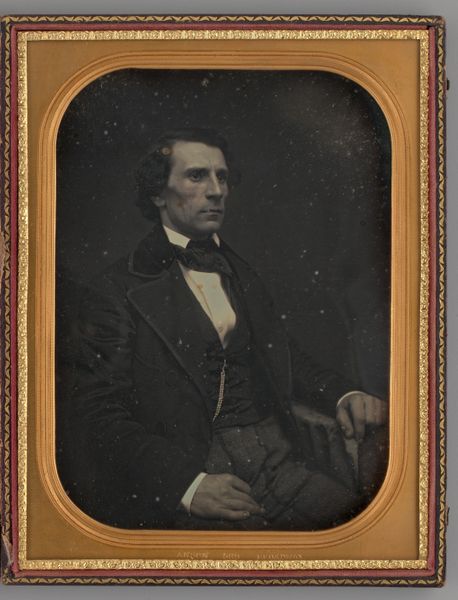

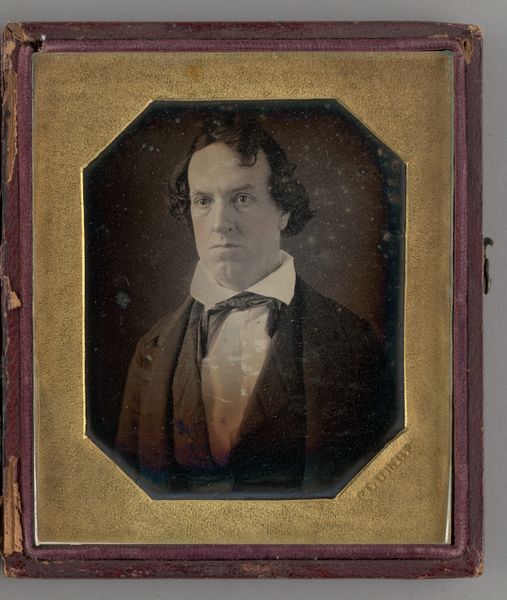

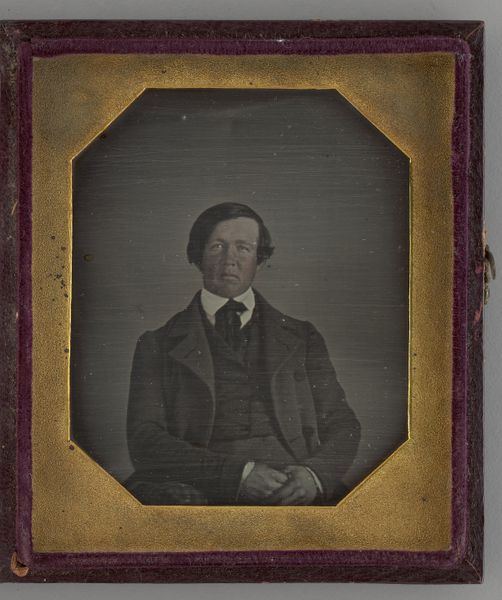

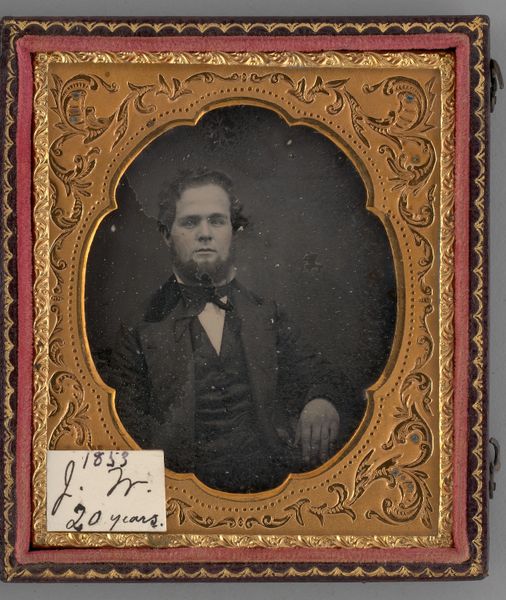

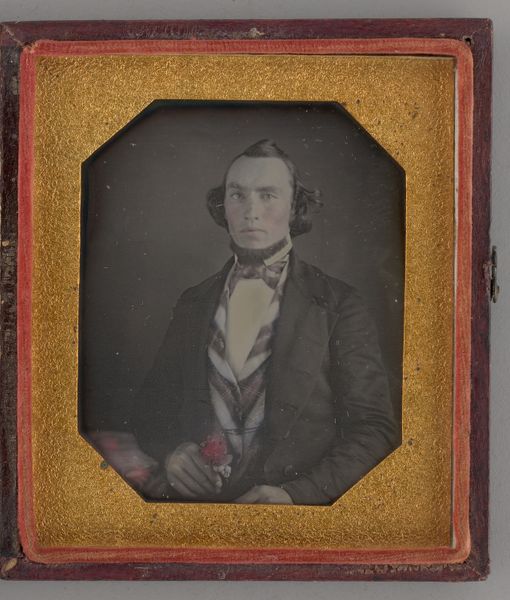

Untitled (Portrait of Seated Man with his Arms Crossed) 1848

0:00

0:00

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

geometric

#

romanticism

Dimensions: 10.1 × 8.2 cm (4 1/4 × 3 1/4 in., plate); 11.2 × 18.8 × 1.3 (open case); 11.2 × 9.4 × 1.8 cm (case)

Copyright: Public Domain

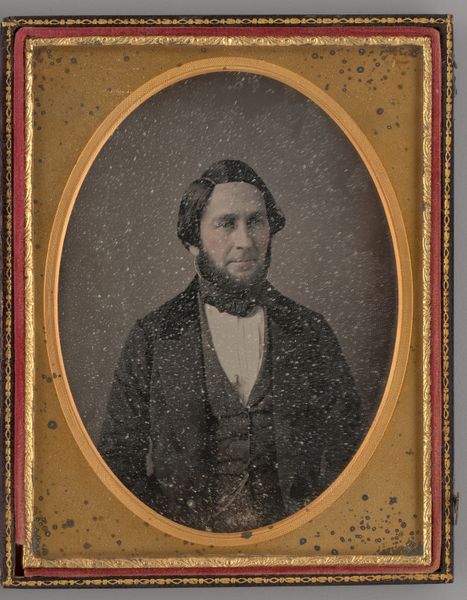

Curator: Here we have an untitled daguerreotype portrait of a seated man with his arms crossed, dating back to 1848. It’s a striking example of early photographic portraiture. Editor: There's a strong air of formality to it. He looks rather stoic, almost guarded, doesn’t he? The crossed arms amplify that sense of distance. What kind of social scripts are at play here? Curator: Indeed. The portrait encapsulates so much of 19th-century ideals: masculinity, reserve, a certain economic standing implied by his attire. Remember, commissioning a daguerreotype was a significant investment for many at the time. The choice to portray oneself this way reflects careful considerations of public image and social aspirations. Editor: Absolutely. Looking at his slightly melancholic expression, I wonder about the tensions simmering beneath that carefully constructed image. Think about the rapid industrial and social changes of the 1840s—how would anxieties of class and status intersect? What’s reflected back at us? Curator: That tension you're picking up on probably stems from the clash between Romantic ideals and the stark reality of a quickly changing world. This era saw a fascination with interiority juxtaposed against the exterior expectations of propriety. Photography provided a novel medium to capture, but also to subtly manipulate, that performance. Editor: Right. The very act of sitting for this daguerreotype involves layers of consent and self-presentation. Considering this was taken just before the major social upheavals around abolition and early women’s movements, it acts as a powerful snapshot of privilege caught in time. We might consider questions of who gets remembered, and how, through the photographic gaze. Curator: Precisely. What’s especially significant about this piece within museum contexts is not merely the image itself, but how it informs and complicates the grand narratives we create. It’s a quiet disruption. Editor: A valuable glimpse, then, into a complex historical moment—a portrait of more than just one man. Curator: Indeed. These early photographs ask us to see the social landscape that developed and made such careful performance possible.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.