daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

romanticism

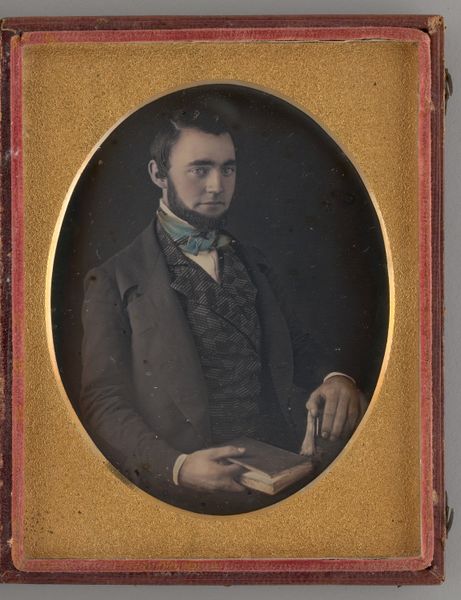

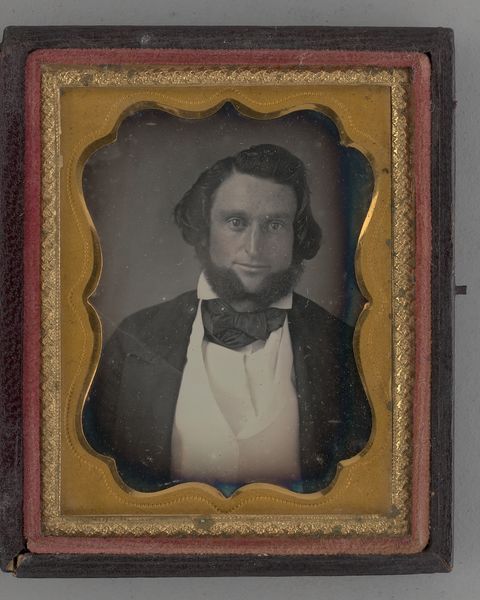

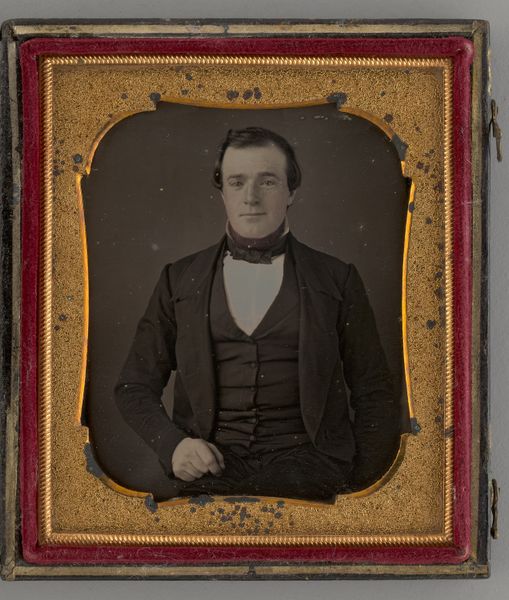

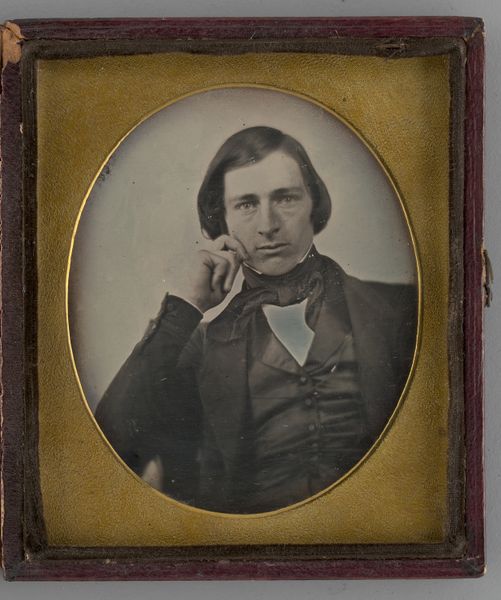

Dimensions: 8.1 × 7 cm (3 1/4 × 2 3/4 in., plate); 16 × 9.3 × 1.1 cm (open case); 8 × 9.3 × 1.7 cm (case)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This haunting image before us is an untitled portrait of a man, rendered in 1845, using the daguerreotype technique. It resides here at the Art Institute of Chicago. What are your initial thoughts on this peculiar portrait? Editor: Peculiar is right. There's something captivating about the texture—that almost metallic sheen characteristic of early photography. And look at the ornate casing around it, quite a contrast to the subject’s stern face and somewhat rumpled clothing. I'm drawn to the contrast between his refined presentation and the very human imperfection in the photographic reproduction. Curator: I am immediately struck by the sitter's ambivalent gaze. It's both direct and distant, revealing something of the tension between performance and genuine presence so often found in early portraiture. This image, beyond its material form, represents a significant step in democratizing image production; making portraits more accessible and redefining how the growing middle class could perform their identity through image making. The ambivalence in his gaze speaks of both promise and precarity for this new social class. Editor: Interesting. For me, it's the visible process. Knowing this is a daguerreotype, that unique alchemical dance of silver and mercury, you begin to appreciate it as both object and image. The fact it’s a unique image, with no negative to reproduce, imbues it with a different kind of significance, a direct relationship between the sitter, the process, and the object produced. It makes you consider the skill involved and the cost involved; portraits were becoming cheaper, yes, but this medium involved materials like iodine, bromide, silver and mercury; whose labour produced them, under what conditions were the workers who fashioned the gilded frame working? Curator: Absolutely. And while the medium made portraiture increasingly available, access remained complex, interwoven with socioeconomic structures and cultural narratives. For many, this represented an entirely novel experience of self-representation. Moreover, portraiture had largely been associated with elite circles. In viewing this work through an intersectional lens, we recognize that for working class folks, or women especially, even such accessible methods of self-representation remained entangled within established power structures that affected matters of agency and personal narrative. Editor: That tension is certainly visible; he is simultaneously performing and being constrained. In any case, viewing this portrait offers an interesting case study for thinking through the relationship between new modes of image production, class dynamics, and the labour that facilitates them. Curator: Indeed. I leave here more attuned to the nuanced interplay of agency and structural constraints shaping individual and collective identities, even in something as apparently simple as a portrait. Editor: And I find myself appreciating not just the image, but the social network and complex production required to yield it. A portrait of material processes as well as an individual.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.