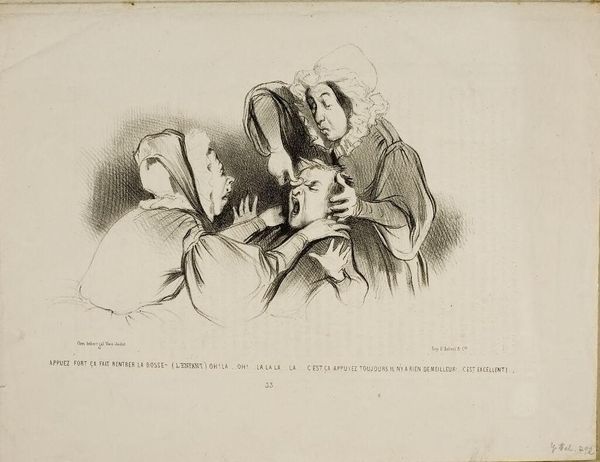

A Fair Reward Presented in 1800 by the Un-Prudish Savages of North America to Louis-Philippe of Orléans, surgeon and expatriate, but still a Frenchman. (I salute you, gracious Black Lady, the Lord is with you.) A Namaquan Ave Maria, plate 466 1835

0:00

0:00

drawing, lithograph, print, paper

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

lithograph

# print

#

french

#

caricature

#

figuration

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

france

Dimensions: 202 × 265 mm (image); 265 × 347 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This lithograph by Honoré Daumier, dating back to 1835, presents us with quite the loaded scene. Its full title, rather verbose I must say, is "A Fair Reward Presented in 1800 by the Un-Prudish Savages of North America to Louis-Philippe of Orléans, surgeon and expatriate, but still a Frenchman. (I salute you, gracious Black Lady, the Lord is with you.) A Namaquan Ave Maria, plate 466". Editor: Woah, that title alone is doing a lot of work! My immediate reaction is one of unease. The contrast between the delicate lines of the figures and the grotesque expressions... It’s disturbing, unsettling, and feels intentionally provocative. The sharp details achieved in lithography heighten the drama and the slightly repulsive quality of the scene. Curator: The choice of lithography is fascinating here. Daumier masterfully utilizes the grease-based medium to create those deep blacks and nuanced grays, it seems deliberately chosen to give the image that gritty, journalistic feel aligning with its satirical intent as it originally appeared in "La Caricature." One has to wonder about the paper stock itself given how widespread printing was. Editor: Absolutely, the reproductive medium and distribution method are essential. It’s crucial to consider this within the broader context of French political satire in the 1830s. Daumier is not simply creating an image; he is participating in a visual discourse critiquing power, specifically Louis-Philippe. He highlights the perception of Louis-Philippe’s compromised position and association with colonial enterprises through a loaded scene portraying him in bed with racially charged figures. This intersectional commentary attacks notions of power, race, and class. Curator: The depiction of Louis-Philippe himself is quite telling. Observe the almost sickly pallor contrasted against the so-called 'savages.' It hints at decadence, an unhealthy dependence, perhaps? Daumier really exploits the tonal range achievable with lithographic crayon on stone here to drive his narrative. Consider the labor involved in preparing the stones, inking, and pulling each print. These were made for wide distribution, affecting how quickly such narratives spread among social classes. Editor: And what does it say about representation? These "un-prudish savages" are hardly afforded any agency or dignity; instead, they serve to expose and indict Louis-Philippe’s own hypocrisy and complicity. The gaze is inherently colonial. Furthermore, by calling attention to his role as "surgeon and expatriate", Daumier reminds us of Louis-Philippe’s own shifting roles. The piece demands we deconstruct power structures at play and question who gets to control these narratives. Curator: A fascinating piece to unravel indeed, laying bare the complexities of political satire and its production value in early 19th-century France. It is interesting to examine what it shows us regarding French colonial involvement as seen from Daumier's view and the lithographic means. Editor: Yes, I concur. An example of how art acts as a conduit, forcing dialogue surrounding race, colonial exploitation, and social criticism across decades.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.