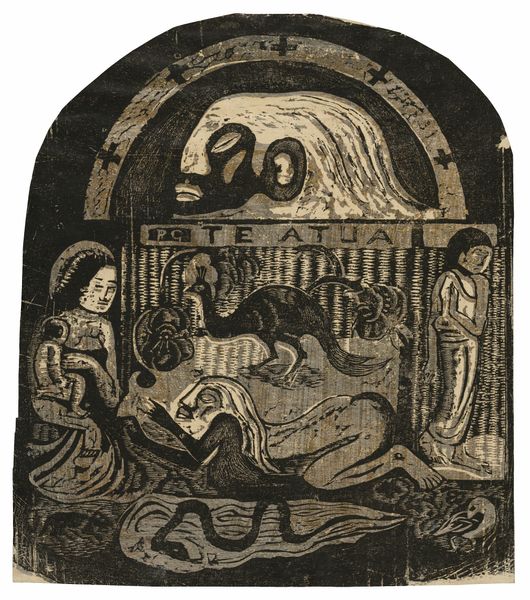

![Te Atua (The Gods) Small Plate [recto] by Paul Gauguin](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzNiNzBmNzdlLTc4NzQtNDFlMi05OGUxLTY5NDZhMjA1MzFiZC8zYjcwZjc3ZS03ODc0LTQxZTItOThlMS02OTQ2YTIwNTMxYmRfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

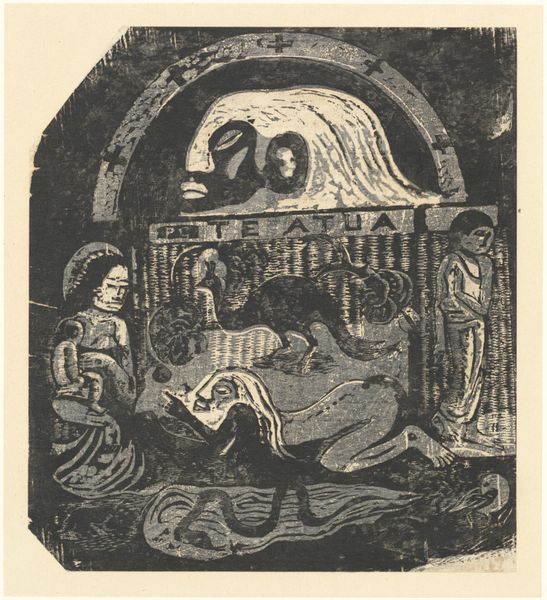

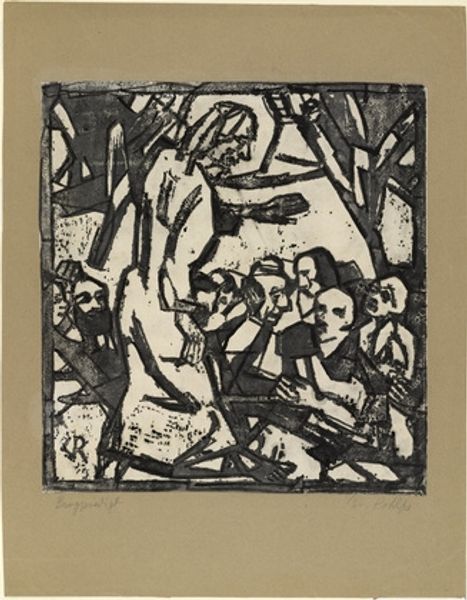

print, woodcut

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

symbolism

#

post-impressionism

Dimensions: image: 24.1 x 22.9 cm (9 1/2 x 9 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: The blocky forms almost vibrate—it’s like a visual echo rippling through this little print. It feels like a half-remembered dream, or a myth trying to claw its way into the waking world. Editor: You’ve pinpointed a central tension in Gauguin's work, which is clearly displayed in this woodcut, Te Atua (The Gods). Dating from after 1895, it invites viewers into a constructed vision of Polynesian spirituality, filtered through a post-Impressionist lens. But is it respectful, or appropriative? Curator: That's the tightrope walk, isn’t it? I mean, look at those thick, raw lines! There's such power in that simplicity. He's simplifying forms to get at something essential…even if that essential thing is more about his own yearning. The Tahitian figures become vehicles for exploring primal feelings. It's like he’s trying to unearth some fundamental human connection. Editor: Exactly, and it's crucial to analyze those "primal feelings." Gauguin simplifies, but also exoticizes and romanticizes. He actively crafts an idea of the "primitive" in opposition to what he saw as the stifling constraints of European society. Take for instance the title itself, it is already loaded with colonial connotations; in doing so, he inevitably distorts Indigenous spiritual beliefs and practices to align with his personal artistic and philosophical agenda. Curator: Yeah, he's definitely not doing documentary work here. But there's something compelling about his drive to synthesize—even if it's flawed. That central reclining figure, pointing, and the faces clustered nearby--there’s a shared ritual or moment. What is she pointing to? Editor: The figures, composed and arranged as they are, speak to the broader societal narrative in which Gauguin engaged—one deeply embedded in the colonial project. Gauguin's yearning for an escape, coupled with the European gaze, inevitably resulted in an uneven power dynamic and misrepresentation. Curator: But does that mean the art has no value? Is it permanently tainted? Editor: I’d argue that confronting those uncomfortable questions—that is where the value lies. Gauguin forces us to see the relationship between the artist, his subjects, and the society that shapes his vision, allowing us to actively deconstruct these portrayals. Curator: So, even in its… problematic-ness, this small print can be a pretty powerful tool, I think. Editor: Precisely; a reminder of art's ability to both reflect and shape our understanding of cultural exchange and power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.