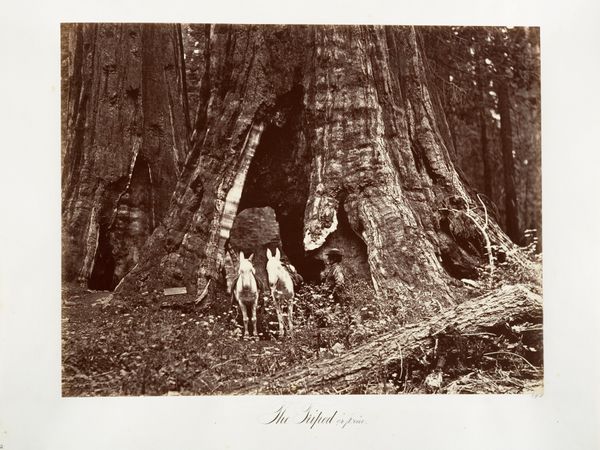

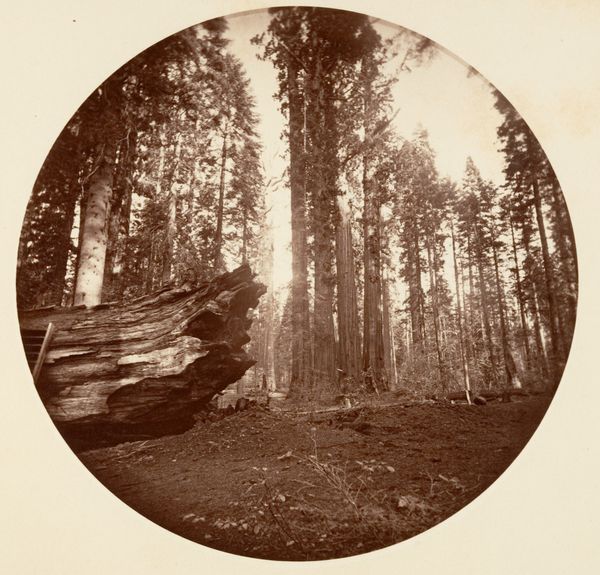

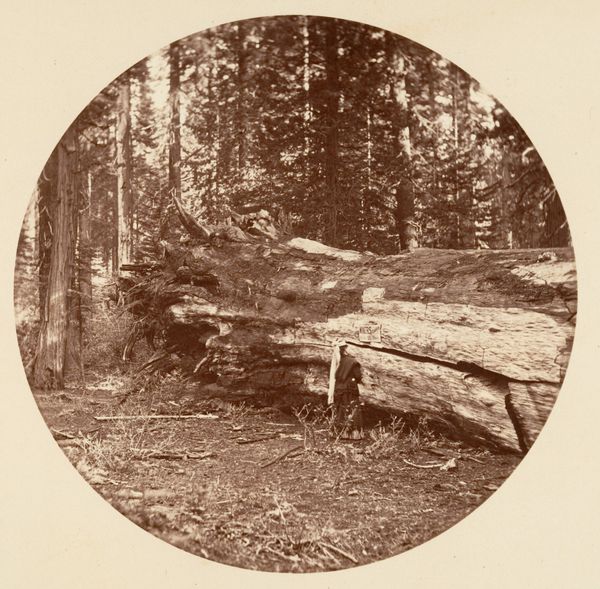

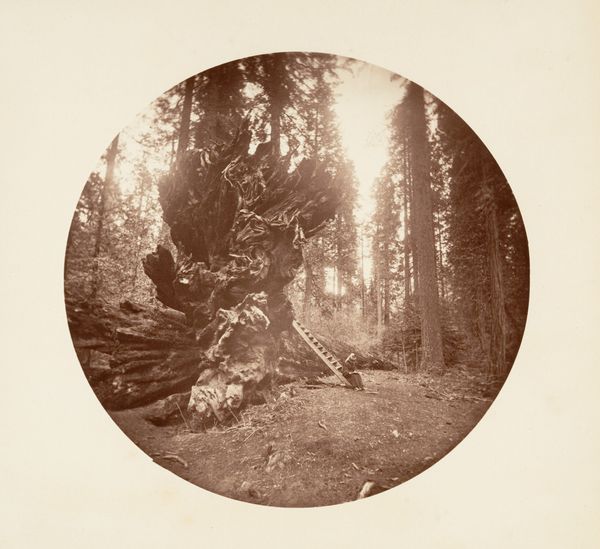

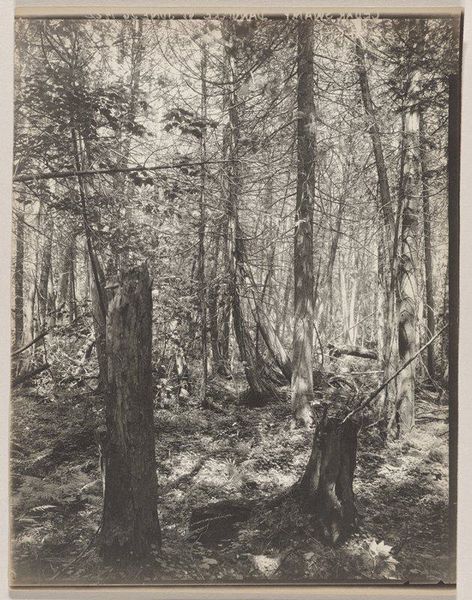

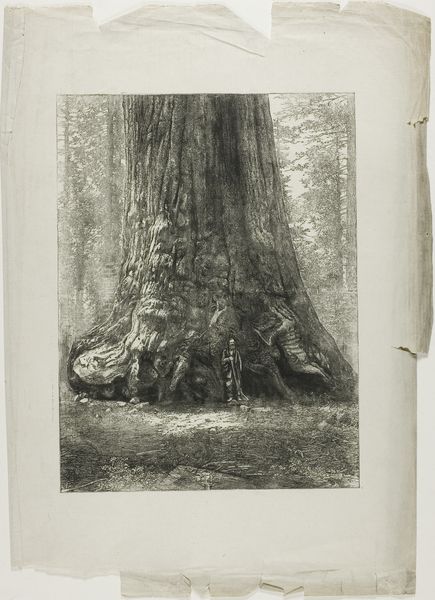

The Father of the Forest, 112 feet circumference, Calaveras Grove 1865 - 1866

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

forest

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

hudson-river-school

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is "The Father of the Forest, 112 feet circumference, Calaveras Grove," a photograph captured by Carleton Watkins between 1865 and 1866. He used the gelatin-silver print medium. What is your immediate impression? Editor: Haunting. The cavernous opening in the fallen tree looks like an empty eye socket staring up at the sky. There's such a sense of loss and perhaps even warning, in the way it’s presented. Curator: That reading is compelling. Watkins, aligned with the Hudson River School, focused on grandeur, but also the resource potential. How might we read his choice to picture this fallen giant, given its immense size? Editor: Well, I see a memento mori. It’s not just a tree; it’s a symbol of mortality. The immense scale reminds us of time, endurance, and ultimately, decay. The image, in capturing this fallen giant, encapsulates the end of an era, or at least, the inevitable decline. What kind of symbol did it evoke for Americans when it was initially displayed? Curator: These photographs coincided with increased industrialization and westward expansion. Watkins, in producing these large-scale photographs and advertising them across the country, was contributing to an understanding of nature as both beautiful and ripe for industry. Note that even its fallen state, the Father is named and measured as a spectacle for public engagement. The making of the image involved the labor of moving equipment through challenging landscapes. His choices speak to a burgeoning consumerism. Editor: That contextualization makes the picture much darker. I was focusing on it as an independent symbolic statement. Watkins may have been unintentionally forecasting exploitation—foreshadowing environmental costs—through this photographic encounter. Curator: Or he could be seen as fully complicit! His work definitely complicates the notion of a purely reverential vision of nature at that time. There is the idea of land as resources, and photographic documentation as a kind of extraction too. Editor: It just goes to show, the photograph doesn't hold a singular meaning. It accumulates significance across generations. Curator: Indeed. The photograph serves as a relic, evidencing the complex intersections between culture, nature, and industry at a pivotal moment in American history. Editor: It reminds us to think critically about even the most seemingly straightforward images and to consider their wider social and cultural influence, beyond the first impression.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.