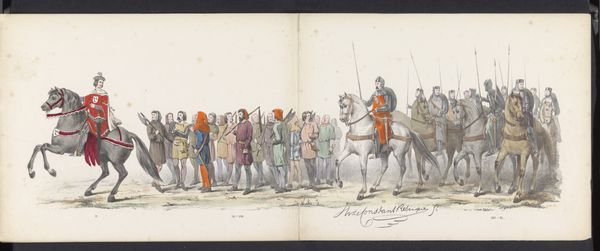

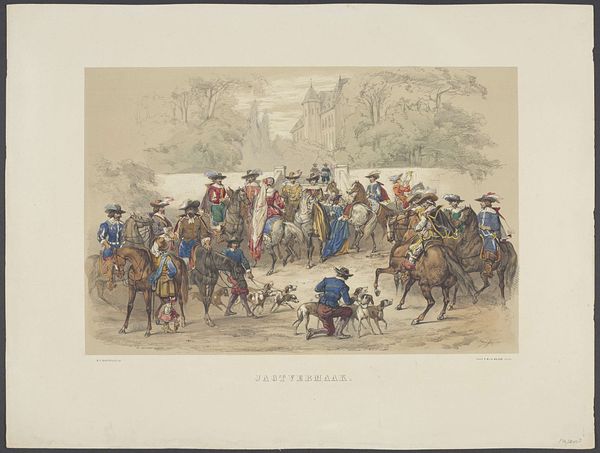

Dimensions: height 550 mm, width 712 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

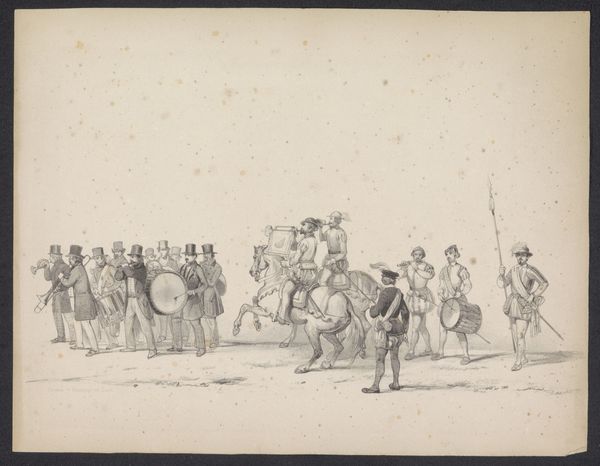

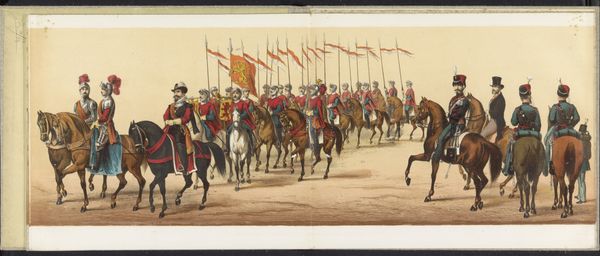

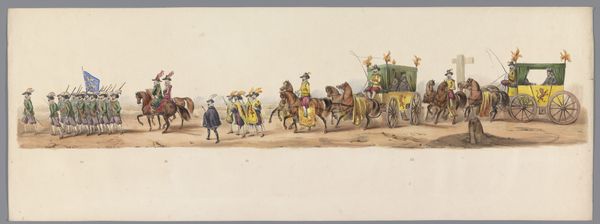

Editor: So, this is Otto Eerelman’s "Groningse Maskerade van 1859: Nederlandse Groep," created in 1859, and it's a print made with watercolor and ink. I’m really struck by the sheer number of figures here. They are all in costume. What’s the story being told here? Curator: It's a fascinating depiction of civic identity expressed through historical masquerade. Consider the timing: 1859. The Netherlands was consolidating its national identity after a period of upheaval. The "Groningse Maskerade" was likely a public spectacle designed to evoke a shared past. Who is included, who is excluded? That’s key. Editor: It seems like a celebration, with all the people, banners, and fancy costumes. It must have been an important part of civic life. Curator: Exactly. But consider the layers. It’s not just celebrating *any* past; it's selectively reenacting certain historical moments, reinforcing particular narratives about Dutch history. What do you notice about the costumes themselves? Are they accurate representations, or are they stylized interpretations? Editor: I think it is stylized; they look historical, but heightened. Also, only certain social classes are depicted; ordinary folk aren't so prevalent in this picture. Curator: Precisely. This wasn't a representation of everyday life, but an idealized and carefully constructed performance intended to unify and celebrate, as well as legitimize, specific power structures and histories. Think about the role the Rijksmuseum itself played in creating this national narrative around the same time. Museums shape public memory. Editor: That’s a good point! I was initially just seeing a historical depiction but it's clearly also about creating a specific image of Dutch identity. Curator: Yes, art doesn't exist in a vacuum. Examining its context reveals a more profound message.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.