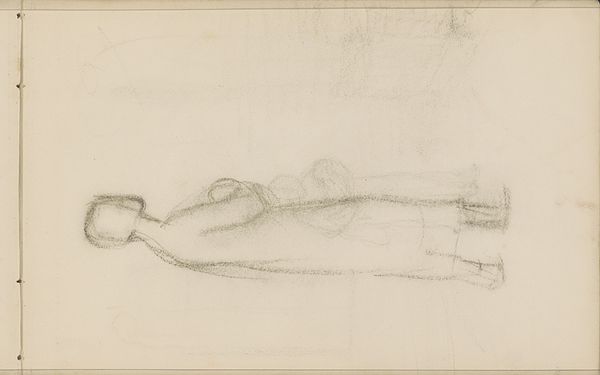

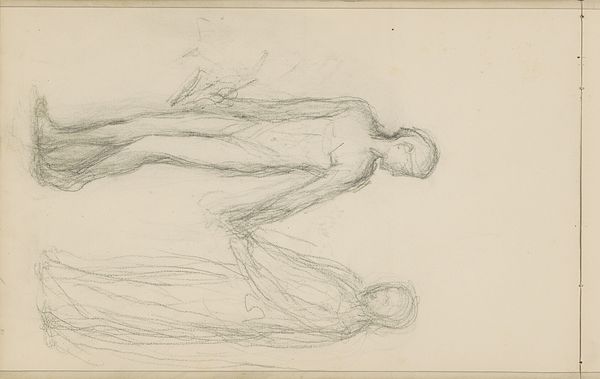

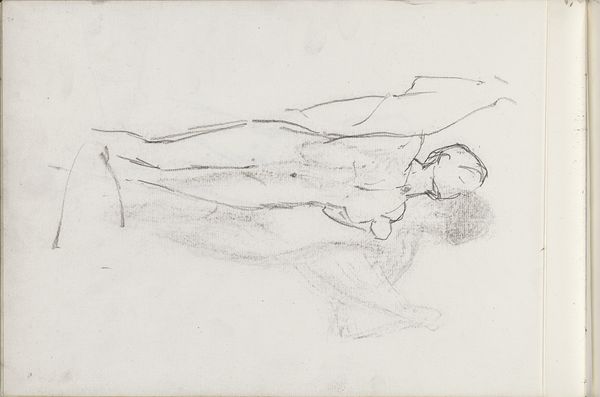

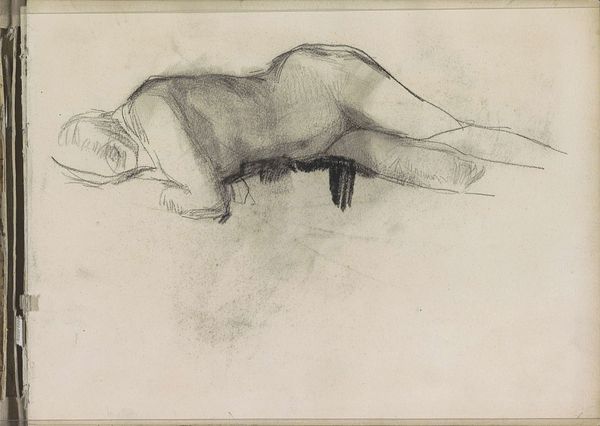

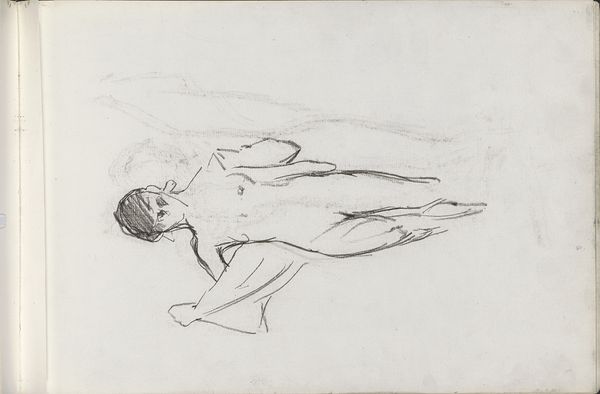

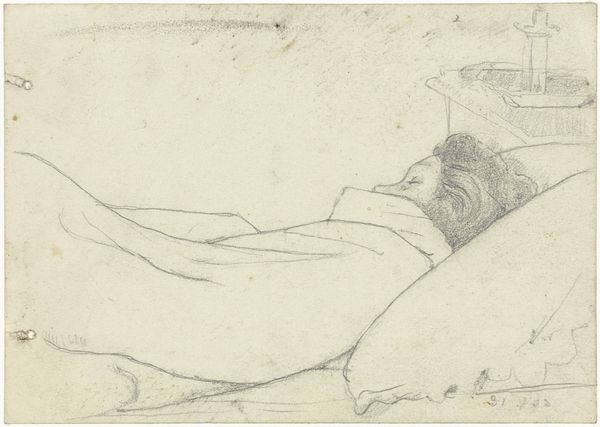

drawing, paper, pencil

#

pencil drawn

#

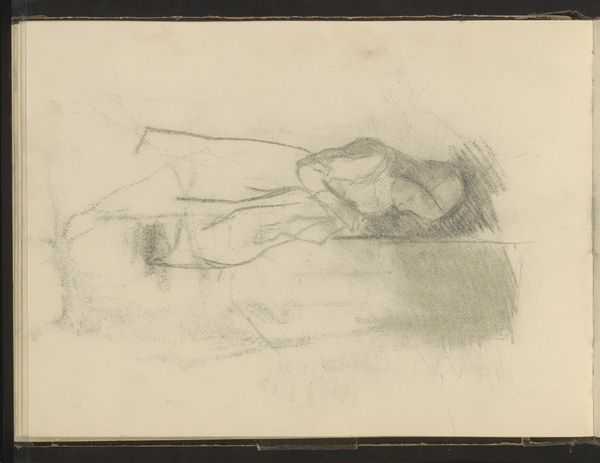

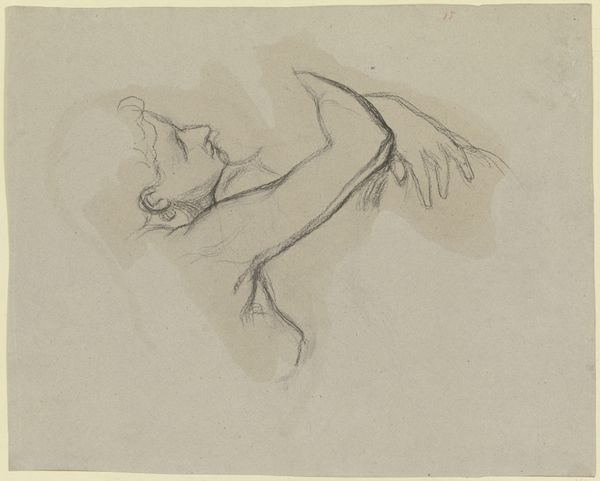

drawing

#

figuration

#

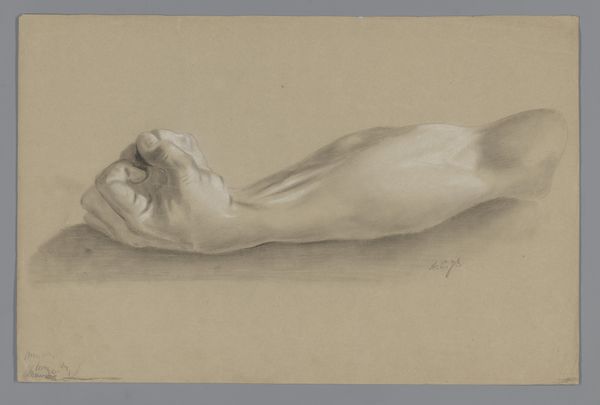

paper

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: My goodness, this pencil drawing… there’s an unsettling intimacy about it. A sense of vulnerability, wouldn't you agree? Editor: The intimacy comes from its sketch-like quality. The labor here appears immediate, like the artist captured a fleeting moment on paper, without worrying too much about finish. The Rijksmuseum tells us it's "Standing woman carrying a baby against her chest" made between 1865 and 1913 by Bramine Hubrecht. It certainly reads as a quick study of form, the economy of line being its most striking element. Curator: Indeed. Notice how the artist utilizes minimal strokes to convey such powerful sentiment, the inherent bond between mother and child represented through touch and embrace? It's almost a universal archetype. Think of the Madonna and Child throughout history... the symbolic power is profound. Editor: That’s a solid interpretive reading. What strikes me is how provisional it seems, how reliant on the qualities of the pencil and paper it is. And perhaps its apparent lack of finish makes it so relatable, it is less idealized than religious painting. You could find drawings like this being produced en masse in workshops and sketchbooks from across this period. Curator: That's precisely what I find compelling – the interplay between the archetypal mother and child, juxtaposed against the seemingly casual creation. A primal, even sacred motif rendered using ordinary tools. But where and when might the setting have been? Who were these ordinary mothers? Editor: Exactly! The focus on materials and labor asks those kinds of contextual questions. For whom were such studies made? Was Hubrecht part of the social reform movements interested in improving the lives of the urban working class and its maternal health crisis at the time? These are vital social context questions we could consider to help the audience delve more deeply. Curator: I appreciate your insights regarding materiality; it deepens the narrative significantly, adding layers beyond mere sentimental recognition. Thanks. Editor: And thank you. Reflecting on the economics of the period makes us appreciate this seemingly simple artwork even more.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.