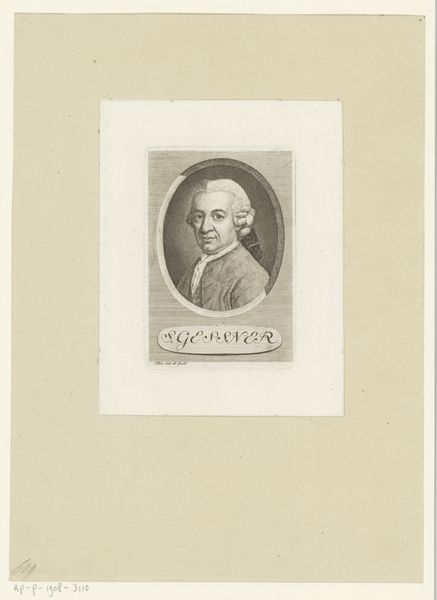

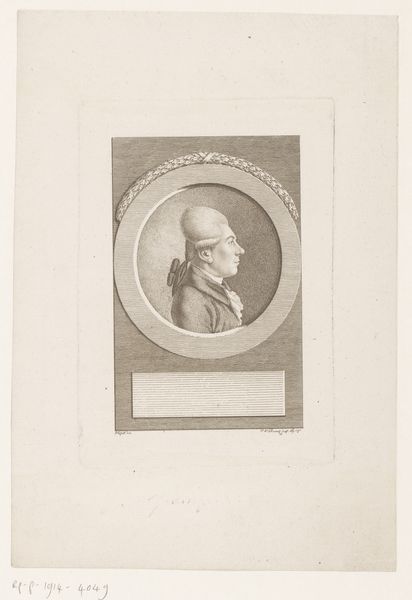

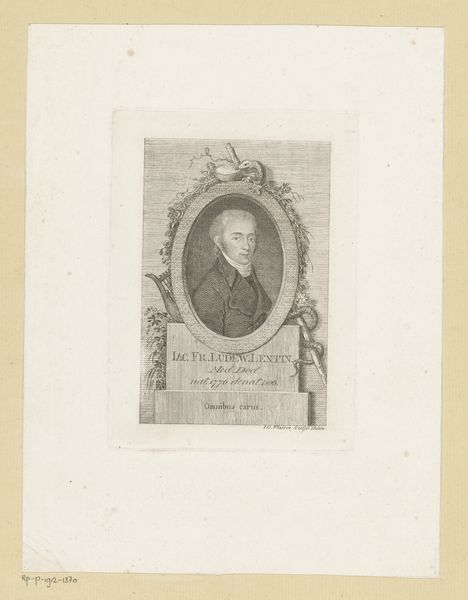

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

old engraving style

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 97 mm, width 58 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Portret van Johann Peter Uz," a portrait of the German poet Johann Peter Uz by Christoph-Wilhelm Bock, dating back to 1790. It’s currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first thought is the incredible detail rendered by engraving—such fine, intricate work to capture his likeness. It seems small in scale, designed to be intimately viewed, doesn't it? Curator: Absolutely. And it's important to note that engravings like this served as vital methods for disseminating information and propagating particular notions of self and societal ideals during the late 18th century. Bock uses a neoclassical style here. I see ideas of rationalism and order reflecting a desire for clear and idealized representation of important figures. How might Uz’s social position at the time have affected the way Bock designed the engraving? Editor: Considering its process, engraving as a medium democratized image production and consumption to a degree. Bock chose this medium so people who may not have ever seen this figure could start creating a shared view on this person's image and status, correct? The background reminds me of woven cloth and adds tactility; you can almost feel the individual lines cut into the copperplate used to make the print. The labor put into it, considered against the accessibility of the print, seems to raise questions of class and knowledge. Curator: Precisely. He was, in essence, branding Uz through reproductive print media as an enlightened intellectual. His direct gaze almost confronts us. It prompts us to confront the social expectations and position this German poet might be in when trying to promote the enlightened thinking that emerged from the Age of Reason. I notice a degree of vulnerability in his smile, don't you think? Perhaps suggesting some insecurity over whether enlightenment ideals were effectively accessible to, or even welcome to, all. Editor: Indeed, but the portrait is not just about enlightenment ideals; it’s an object made within a specific system. Who commissioned the piece, who bought and collected such portraits, and where they were displayed…all part of this engraving’s history as a commodity and means for visual literacy among certain groups in the eighteenth century. Curator: That’s very insightful. This portrait is a portal into exploring identity, and the materials and networks around the artist who created the piece. Editor: The way the object itself reflects history and the way it impacts present consumption patterns, which, like then, reflect an ideology based on social position, race, gender and economic status. It adds layers to understanding print and people’s relation to reproducible work in general.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.