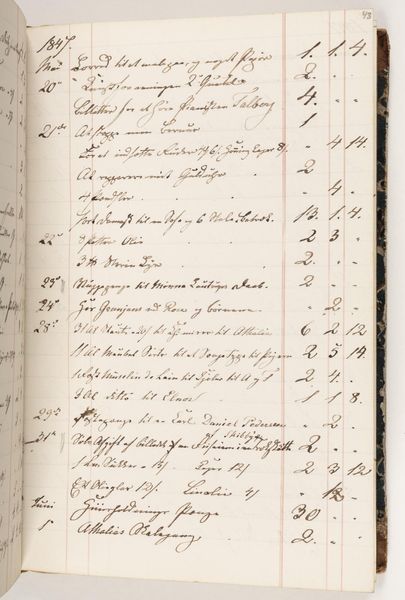

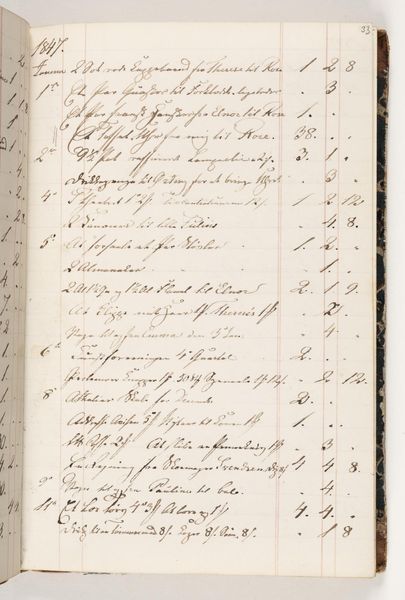

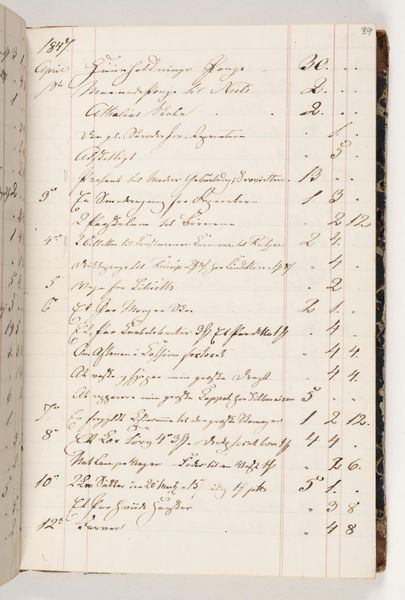

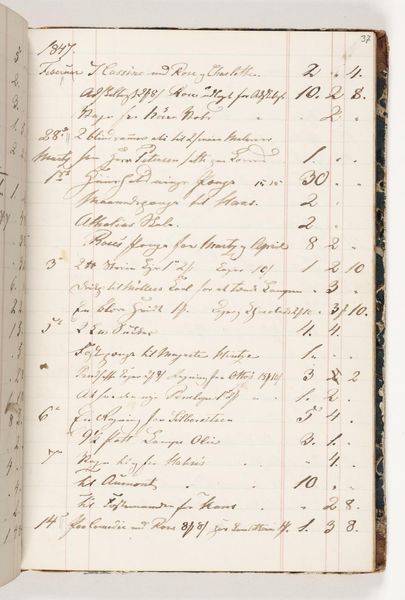

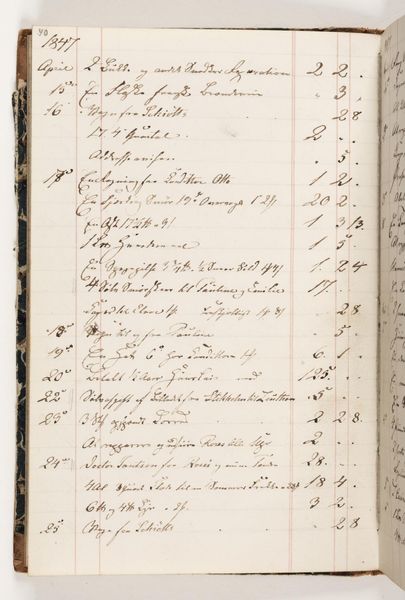

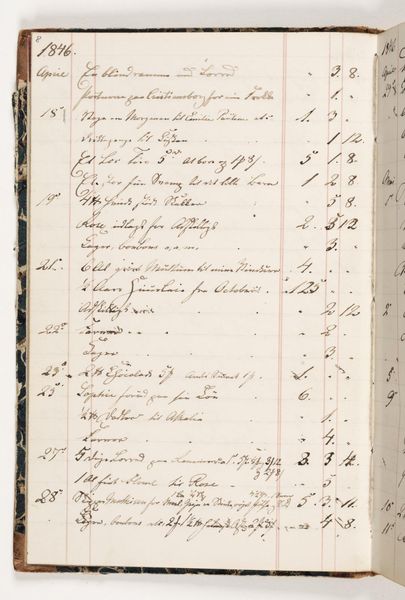

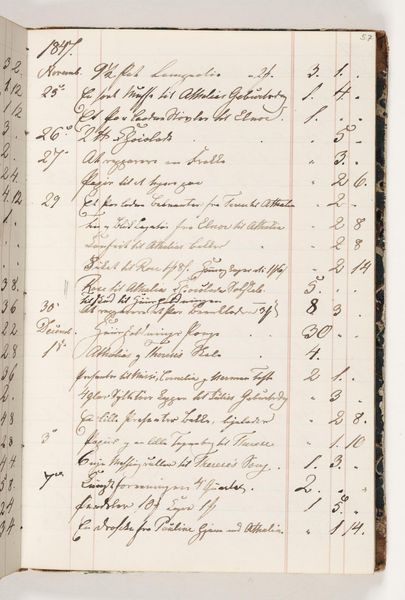

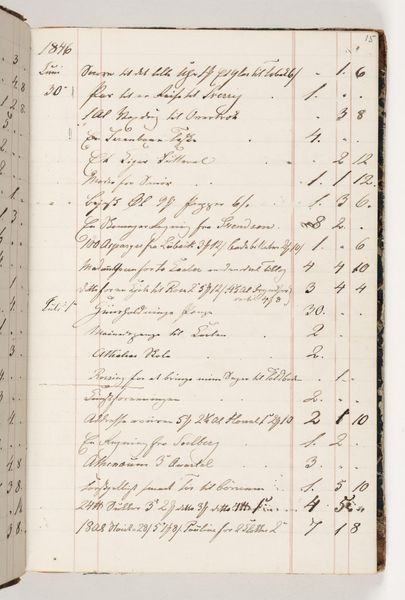

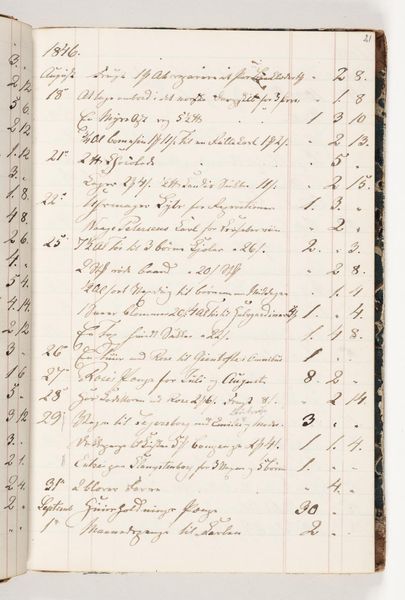

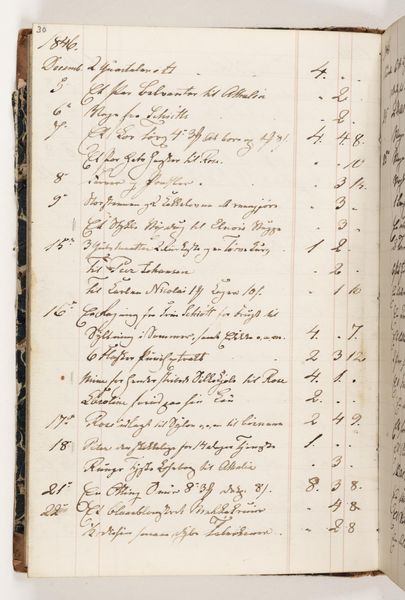

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

#

paper

#

ink

Dimensions: 200 mm (height) x 130 mm (width) (bladmaal)

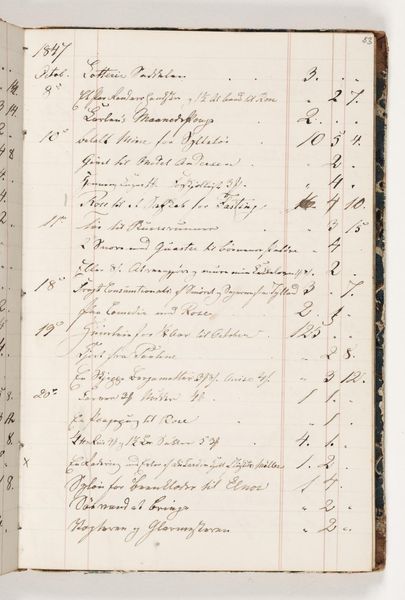

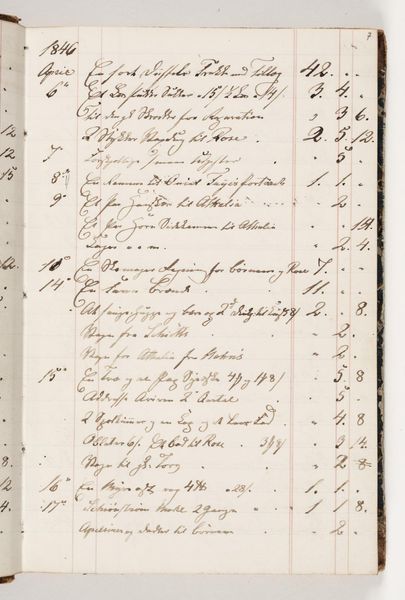

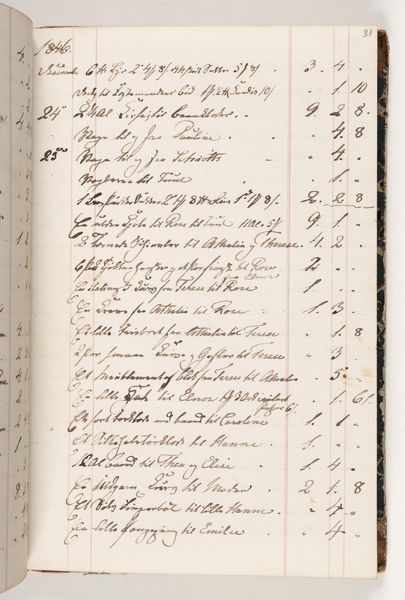

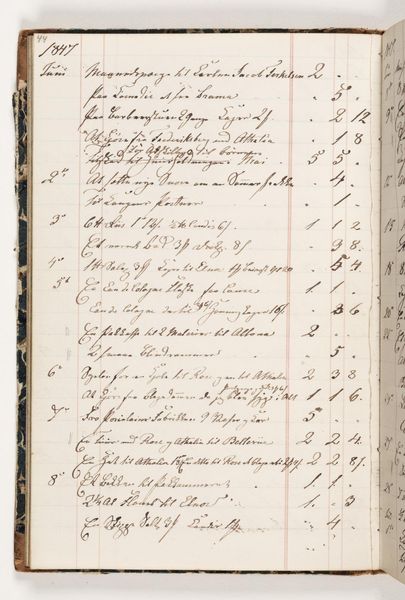

Curator: The act of transcription itself holds value. Before photography and other mass means of reproduction, how was labor distributed in preserving the historical record? Editor: Right, here we have Martinus Rørbye’s "Regnskab 1848," a ledger created in 1848 using ink on paper. It's literally just handwriting – script, I guess? It almost looks like an illuminated manuscript, strangely. What stands out to you? Curator: Look at the meticulous formation of each character, the standardized column on the right, clearly tracking numeric values... This wasn't haphazard work. It’s record keeping, a form of labor intertwined with systems of commerce and governance. What labor and materiality produced this accounting document, who performed the physical writing of this work? Editor: I never really thought about that before! It kind of challenges this assumption I have of fine art always being displayed in gilded frames. The ink itself has value here; the paper and the writing implement were fabricated by human effort somewhere. Curator: And whose labour, and for whose purposes, do we see evidence of in these columns? Were such positions of maintaining the records open to all? It forces a look into societal context, questioning assumptions on accessibility. Editor: I think you’ve helped me recognize the significance of what may look commonplace – how labor, societal roles, and even the economy impact art-making in different eras. Thanks! Curator: And likewise, your observations encourage fresh appraisals for artworks commonly placed within certain established traditions of valuation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.