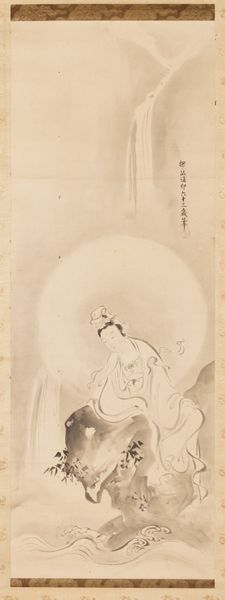

painting, hanging-scroll, ink, color-on-paper

#

medieval

#

ink painting

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

japan

#

figuration

#

hanging-scroll

#

ink

#

color-on-paper

#

line

#

japanese

#

yamato-e

Dimensions: 38 1/4 × 12 13/16 in. (97.16 × 32.54 cm) (image)68 1/2 × 17 3/8 in. (173.99 × 44.13 cm) (mount, without roller)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Before us, we have "White-robed Kannon," a hanging scroll rendered in ink and color on paper, attributed to Kenkō Shōkei from the late 15th century. It’s currently held in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: It evokes such a sense of calm, doesn’t it? The soft gradations of ink wash create a misty, almost dreamlike atmosphere. The figure seems to dissolve into the landscape. Curator: Precisely! This reflects the Kannon's role as a compassionate Bodhisattva, deeply connected to the natural world and the suffering within it. Images of Kannon became increasingly popular during periods of social upheaval, offering solace and the promise of salvation to the populace. Editor: The composition is striking too. The figure is framed by the landscape, with the strong verticality of the waterfall contrasting with the gentle curve of her reclining form. That halo or mandorla of light behind her further isolates and elevates her figure within the scene. The waves below appear almost decorative, contrasting sharply with the ink-washed mountains behind. Curator: That contrast is key. The delicate "Yamato-e," or Japanese-style painting, elements alongside the figure are there to appeal to local tastes, while the overall form aligns to wider Japanese cultural concerns related to trade with, and the religious culture imported from, mainland Asia. Consider how carefully constructed her reception would have been at the time for varied audiences and social locations. Editor: You’re right, there’s a visual dialogue between different artistic languages here. Look at the economical use of line, capturing the folds of her robe with such elegance, yet maintaining such subtle dynamism and rhythm in her garments. Curator: And consider, too, the institutional context; religious iconography, especially from major workshops such as that which Kenkō Shōkei headed, played a vital role in shaping social values and promoting specific Buddhist teachings. Powerful religious artworks disseminated through the established network of temples helped support the shogunate at the time. Editor: The image provides visual tranquility through dynamic composition and ink tonalities—offering something both formally compelling and deeply rooted in religious practices. It definitely draws you in. Curator: Indeed. Examining works like this compels us to recognize the intertwined histories of artistic expression, devotional practices, and political contexts.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Buddhist monks, particularly those of the Zen school, were devoted landscape painters. Like calligraphy, painting was considered part of the spiritual training necessary for enlightenment. Zen monks favored monochrome ink painting due to its simplicity and straightforwardness. The priest Kenkō Shōkei, who served as secretary at Kenchōji Temple in Kamakura, studied Chinese paintings from the Song and Yuan dynasties and became a key figure in the ink-painting circles of Japan. (2013.29.143.1-.3)

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.