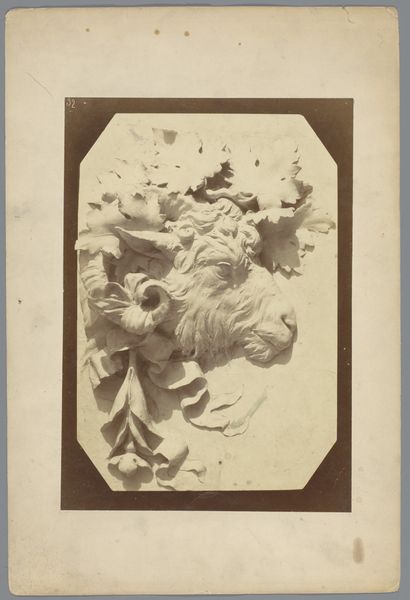

relief, photography, sculpture, gelatin-silver-print

#

relief

#

photography

#

sculpture

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

academic-art

#

decorative-art

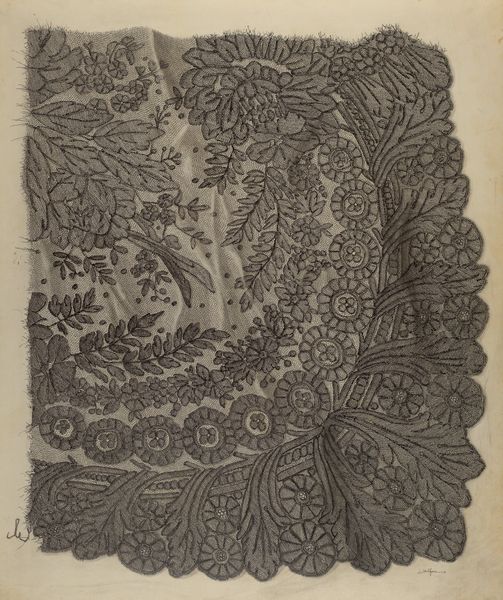

Dimensions: height 278 mm, width 205 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Gustave Eugène Chauffourier's "Relief met een guirlande van eikenbladeren," which translates to "Relief with a garland of oak leaves," dating from around 1875 to 1900. It's a gelatin-silver print of a sculpture. What strikes me is the intricate detail captured in the photograph—almost like the texture is jumping out at you. What do you make of this photograph, viewed through a materialist lens? Curator: The fact that we're looking at a photograph OF a relief is crucial. This image is evidence of reproduction. The photograph flattens the original sculptural work. It allows for widespread distribution and, in essence, turns a unique artwork into a commodity. Think about the labor involved in creating the original relief versus the labor of mass-producing these photographic prints. Whose labor are we really seeing? Editor: That's a good point. So you're saying the photograph shifts the focus from the sculptor's hand to the mechanisms of photographic reproduction and its social implications? Curator: Precisely. We need to consider the means of production: the darkroom processes, the chemicals involved, and who had access to those materials. The choice of a gelatin-silver print—a process that gained prominence in the late 19th century—reflects a specific stage in the industrialization of photography and image consumption. How does this period's emphasis on naturalism play into the choice of this subject matter? Editor: I see what you mean. The oak leaves, a very earthly subject, seem fitting for an era obsessed with photographic realism. It seems so interesting to me now. Thanks for the insight! Curator: My pleasure! It’s a reminder that even seemingly straightforward images have complex material and social histories embedded within them.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.