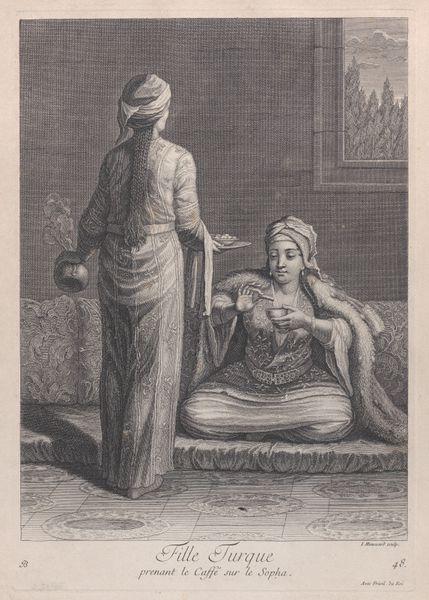

Filles Turques, qui jouent au Mangala, plate 53 from "Recueil de cent estampes représentent differentes nations du Levant" 1714 - 1715

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

islamic-art

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 16 7/8 × 12 5/16 in. (42.8 × 31.3 cm) Plate: 14 1/16 × 9 13/16 in. (35.7 × 24.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

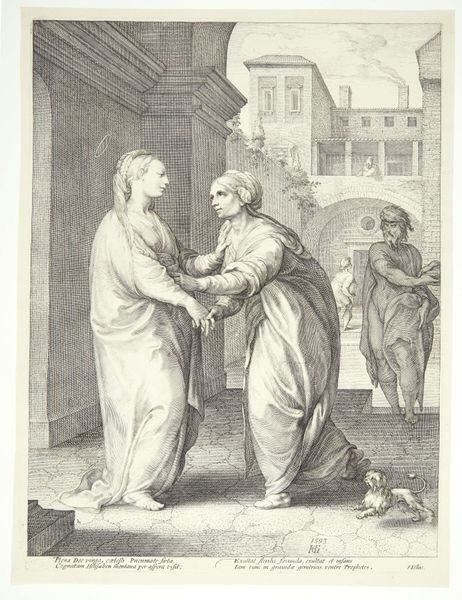

Curator: This engraving by Jean Baptiste Vanmour, titled "Filles Turques, qui jouent au Mangala," plate 53 from "Recueil de cent estampes représentent differentes nations du Levant," dates to the early 18th century, sometime around 1714-1715. It's part of a larger collection aiming to document different peoples of the Levant. Editor: It feels very contained, doesn't it? The composition, with these two women seated close together, gives a sense of intimacy and quiet observation. It is rendered in black and white, very delicate line work in their clothing. It is fascinating, very much of its time. Curator: Indeed. What strikes me is how Vanmour uses this seemingly simple genre scene – two Turkish women playing Mangala – to communicate ideas about the exotic "other." The print, of course, becomes part of the European gaze on the Ottoman world. Note the details of their clothing and head coverings. They are all subtle markers that signify "Turkishness" for a European audience. Editor: And Mangala itself takes on symbolic weight. This isn't just a casual pastime, but a codified representation of cultural difference. We’re not just looking at women playing a game; we are observing a performance of oriental identity. Curator: Precisely. Mangala becomes an emblem of leisure, mystery and an otherness in this setting. How do you read the poses of the two women in the print? Are they participating willingly, or are they self-consciously posing? Editor: It is ambiguous. One is actively engaged in the game, her gaze intent. The other is more passive, almost melancholic. It could be a fleeting expression during a game, but it might also represent the complicated reality of representation itself: The women are subjects, observed and categorized, their own agency somewhat obscured. Curator: Vanmour worked for the Ottoman court for a period. These images became very popular with European aristocracy traveling or residing in Turkey. His depictions fed into both fascination and often skewed views of life there. Editor: Which underscores the power dynamics at play. While we might appreciate the intricate detail and composition as artwork, it’s vital to remember it existed and circulated within a particular political landscape, helping solidify ideas and stereotypes about the East for the Western gaze. Curator: A powerful reminder that images always operate within a context of power and interpretation. Thanks for unpacking this artwork together. Editor: My pleasure, these explorations into how the social and symbolic intersect are always time well spent.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.