![Portret van Mirza Ahmad, die de oudste schoonzoon van Sultan Abdullah is geweest; hij heeft [met de titel?] Ayn al-Mulk als vizier gediend by Anonymous](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzM0NzI1YjQ5LTkwOWQtNDQ3My05Mzg4LTE2YWJlMzQ0YWNjYS8zNDcyNWI0OS05MDlkLTQ0NzMtOTM4OC0xNmFiZTM0NGFjY2FfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

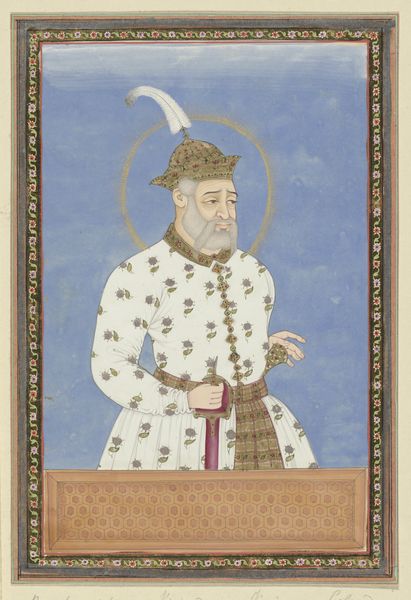

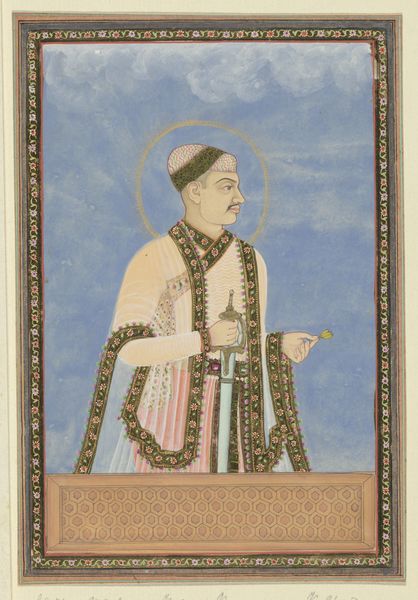

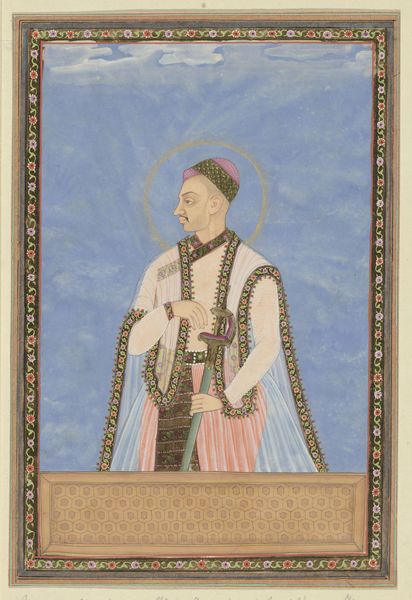

Portret van Mirza Ahmad, die de oudste schoonzoon van Sultan Abdullah is geweest; hij heeft [met de titel?] Ayn al-Mulk als vizier gediend c. 1686

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 203 mm, width 140 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a work titled, "Portret van Mirza Ahmad, die de oudste schoonzoon van Sultan Abdullah is geweest; hij heeft [met de titel?] Ayn al-Mulk als vizier gediend," made circa 1686 by an anonymous artist. The piece, currently housed in the Rijksmuseum, utilizes watercolor. Editor: It's serene, almost melancholic. The pale blues and creams evoke a certain lightness, though the geometric patterns hold my gaze firmly in place. Curator: The subject's attire directs attention. Note the carefully rendered stripes on his robe, balanced against the more florid pattern of his shawl and turban. The use of geometric design on what appears to be the upper part of a wall, combined with a floral border, strikes me as deliberate. The anonymous artist clearly intends to guide the viewer. Editor: Absolutely, it appears every material shown holds meaning. I'm curious about the watercolor technique employed; one imagines the laborious layering to achieve such precise detail on woven fabrics and floral embellishments. Think of the artist's labor, not just artistic expression but craft production within the court. How accessible were such portraits, or their raw materials, beyond elite circles? Curator: That tension interests me—the subject of elevated rank presented in what seems almost intentionally flattened perspective, heightens his symbolic importance while, arguably, democratizing the medium itself. The composition directs us to consider the concept of Islamic art within the traditions of Mannerism. Editor: It’s the artist's choice of materials –the way these watercolors capture light that speaks of an interplay between culture and creation. The geometric designs that, while decorative, seem to offer insight into mathematics and societal class as well as cultural interactions through craft, tools and materials, too often unacknowledged. Curator: Precisely, that play of cultural symbolism embedded within form… fascinating! Editor: The choices reflect something bigger— the portrait is beyond a simple depiction. It is a material index into this individual’s status. It offers tangible insights into the dynamics and means of production for 17th century Islamic portraiture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.