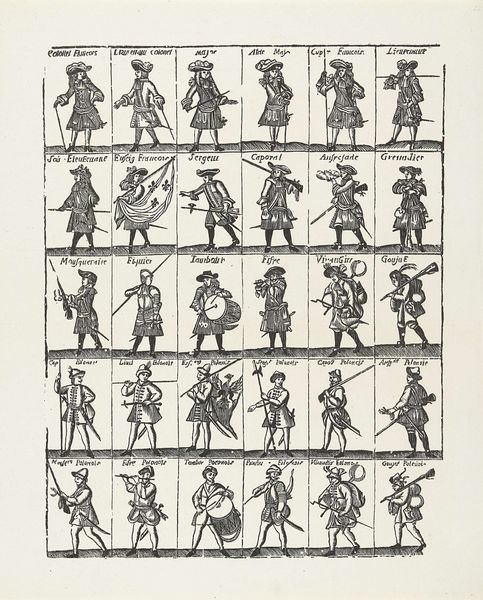

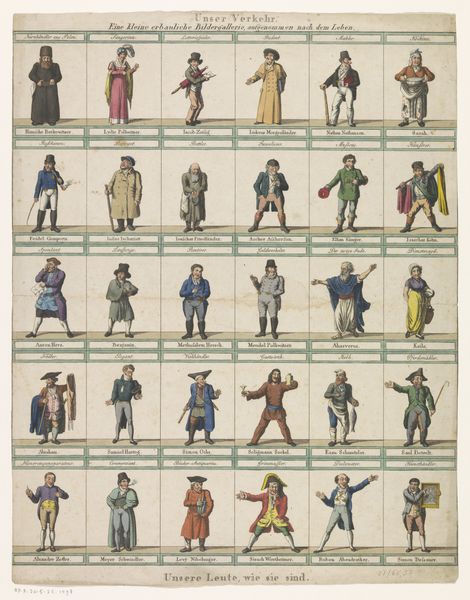

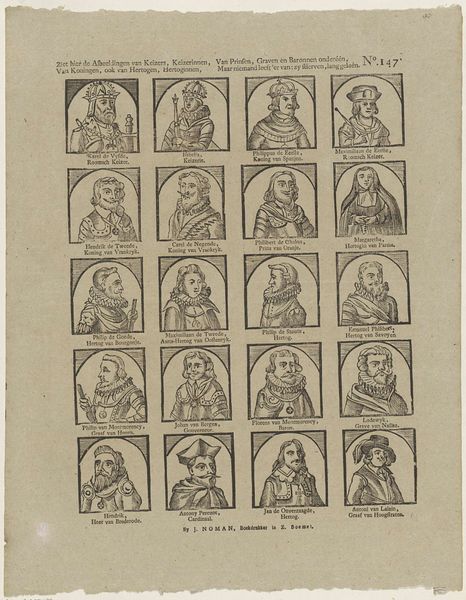

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

figuration

#

orientalism

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 377 mm, width 315 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: At first glance, it resembles wallpaper—but no, it's an intriguing print called "Bédouins" made sometime between 1827 and 1894. Editor: There’s a stark, almost repetitive quality to it. It gives a mass produced effect, yet each figure seems unique despite the obvious attempts at uniformity. It is giving nineteenth century factory production! Curator: Indeed. It seems a nod toward the Orientalist fascination with the Middle East and North Africa. This image would contribute to constructing ideas of the 'other'. We're seeing cultural stereotyping as a form of knowledge here. Notice how the figures are generalized, archetypal. Editor: I’m more intrigued by the printing process itself, most likely some form of engraving given the era and fineness of the lines. It seems like a potentially economical means of reproducing these images for wider distribution. Was this meant for textbooks or some other kind of consumption of visual culture? Curator: Likely. The symbols speak volumes: the men’s weaponry signifies strength and power and evokes notions of exotic warriors—even danger. Think of this repeated image, how the culture absorbs it over time. The individual becomes the symbol of an entire people. Editor: You are absolutely right; it does echo a method of replication suited to disseminating visual representations rapidly and cheaply. The use of engraving probably allowed for that replicability, reducing cost per impression to a negligible degree, furthering this symbolic reduction of humanity in bulk form. It looks more like industrial labour than high art to be fair. Curator: Absolutely, we must view it within its historical and psychological context, with this "Bédouins" print acting as a lens for reflecting societal desires and anxieties in an increasingly complex world. The Orient becoming a projection screen. Editor: Ultimately, I look at this and think less about romance or projection. Instead, I see industry. Its message is inextricably tied to its method of creation: these symbols only matter insofar as they serve as consumable pieces on a production line that is nineteenth century life. Curator: Very interesting—both our viewpoints offer valid avenues of appreciation. Editor: Yes, this production is very telling for further analysis!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.